How many angels can sit on the head of a pin? Was it harder for God to create the universe than to create man? In the resurrection, will man get back the rib he lost in Eden?

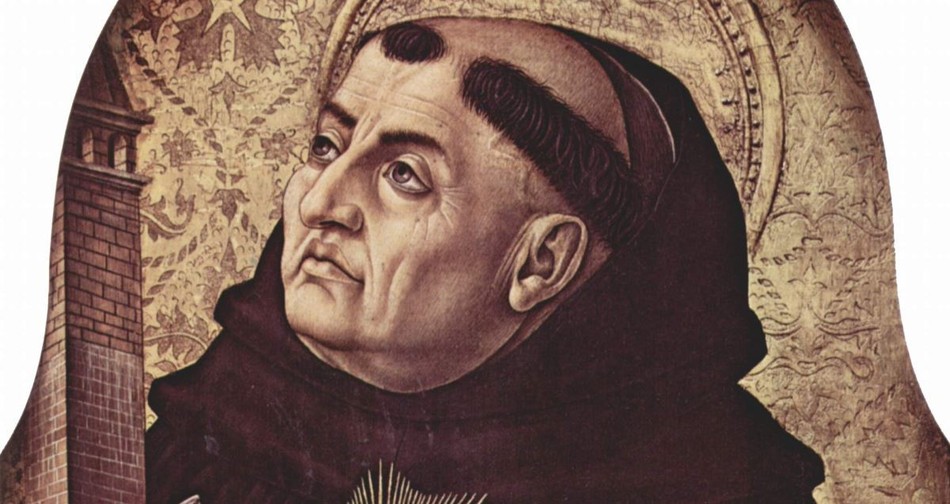

Such questions were debated by the scholastics, the theologians of the Middle Ages. While today we might laugh at such questions, we also can appreciate a certain aspect of their thinking--they took Truth seriously, and they wanted to know every detail about God and his creation. The greatest of all the Scholastic theologians was Thomas Aquinas.

Who was St. Thomas Aquinas?

Thomas was born about 1225 into a dynamic age--the age of chivalry, the Crusades, and Marco Polo. Towns were competing with one another to build taller and more glorious Gothic cathedrals. As the younger son of the Count of Aquino, near Naples, Italy, Thomas was also born into a well-connected family, related to the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick and descended from the famous crusader Tancred.

Yet Thomas lived largely apart from the attractions of this medieval world, focusing instead on affairs of the mind. When he was five, his parents sent him to the prestigious monastic school at Monte Cassino. As his family saw it, Thomas could use his religious education to obtain a lucrative and influential position as an abbot or even archbishop. But this young man had other ideas. While studying at the University of Naples, Italy, Thomas chose to enter the Dominican order, taking a vow of poverty. His parents were outraged when they found out. Being religious was one thing, but being poor, that just wouldn't do. They quickly attempted some damage control.

When his dad got the Pope to offer him the archbishopric of Naples, Thomas wouldn't take it. How about being abbot of the affluent monastery at Monte Cassino? No, Thomas wasn't budging. In fact, he reaffirmed his vows and set out to study with the Dominicans in Paris.

He never got there. His family had him kidnapped along the way, and they imprisoned him in the tower of a castle for seventeen months. Think of it as a kind of cult deprogramming. Thomas' brothers even hired a prostitute to seduce him. When she entered his room, he knew he had better not leave any room for temptation, so he quickly grabbed a firebrand from the hearth and chased her out. Then he branded the sign of the cross in the door.

As the story goes, his mother was moved by Thomas' determination, and she eventually helped him escape out the window.

Strong and Silent St. Thomas Aquinas

He went on to study in Paris and Cologne, where he became the pupil and friend of Albertus Magnus, a renowned German theologian. Since Thomas was a big, quiet man, he gained the nickname of "Dumb Ox." But, recognizing the genius inside, Albertus quipped, "This is an ox whose braying all Europe will hear."

After completing his formal studies, Thomas spent the rest of his life teaching theology in Paris and various papal centers in Italy. During the high Middle Ages, all education was in the hands of the church. The schoolmen, or teachers at the medieval schools, tried to systematize the teachings of Scripture and church writers. The great minds of the age, Anselm, Peter Lombard, Hugh of St. Victor, and Duns Scotus, all set their hand to bring some logical order to the first millennium of Christian thought. Aquinas became the greatest of these systematizers. His mentor was right: the "braying" of this plodding scholar reached throughout Europe and beyond. Some have described Aquinas' thought as a lake with many streams flowing into it and many drawing from it, but not a water source itself. It might be true that there was little originality in his work, but Aquinas organized medieval thinking better than anyone else did.

With the strong Muslim presence in Spain and North Africa, as well as the Middle East, Aquinas was concerned about the spread of Christianity. In addition, works by the Muslim writer Averroes, Jewish teacher Maimonides, and the classical Greek philosopher Aristotle had recently been translated into Latin and were being read by European scholars. How should Christians deal with these non-Christian teachings? In response, Aquinas wrote a Manual Against the Heathen as a missionary tool to use with both Muslims and Jews. In the first three sections, Thomas used logic and reason to prove the existence of God, his character, the creation of the world, and his providence. Only in the last part did he turn to Scripture to establish the Trinity and explain the Incarnation of Christ.

Aquinas' Summa Theologica

Thomas believed philosophy and reason could aid theology, and his proofs for the existence of God are still used in modern apologetics. He was willing to use Aristotle (whom he called "the philosopher") to discover truths in nature and illuminate the Scriptures. He recognized, however, that some Christian doctrines, such as the Trinity and Incarnation, could not be known without God's revelation.

Of course Thomas' masterpiece is Summa Theologica, a work in three books on God, humanity, and the Redeemer. While the Gothic cathedrals were massive structures of stone and stained glass built for God's glory, the Summa was a massive logical structure assembled to help understand the mind of God. Thomas followed a basic method: first asking a question (such as "Is God a body?"); then listing a series of articles with positive answers (Scripture speaks of God's hand or eyes, we are made in God's image); then listing a series of articles with negative answers (God is a Spirit); and finally giving his answer to the question, addressing both the positive and negative articles. With 518 questions and 2,652 articles, the Summa is an amazing compilation of medieval thought on theological issues--but this masterpiece was never completed. One morning while at worship, Thomas had a vision. So overwhelming was this experience of God that he never wrote again. He explained that, compared to what had been revealed to him, all that he had written was "straw." The next year, on March 7, 1274, Thomas died at the Cistercian Abbey of Fossanuova.

In 1323 Thomas was canonized (proclaimed a saint) by Pope John XXII, and in 1567 he was recognized as a "doctor of the church." In fact, he became known as the "Angelic Doctor." In 1879, as the Church faced the skepticism of the nineteenth century, Pope Leo XIII commended Aquinas as the safest guide in Christian thought. Aquinas' reconciliation of faith and reason continued to influence church teaching, even into modern times.

Thomas used his gift of rational argument to serve his church. Non-Catholics can applaud his reasoning on basic doctrines like the Trinity and the Incarnation, while they may still quibble with his stance on other issues. Thomas supported the medieval Catholic doctrines on the sacraments, indulgences, purgatory, and transubstantiation (the teaching that communion bread and wine are transformed into the body and blood of Christ), but papal infallibility and the immaculate conception of Mary weren't yet church dogma. His writings were used extensively at the Council of Trent, which formulated Catholic teachings in opposition to the teachings of the Protestant Reformation. In light of all that, it's no wonder that Martin Luther called Thomas' Summa Theologica "the fountain and original soup of all heresy, error, and Gospel havoc." But modern evangelical Norman Geisler expresses the appreciation of many modern Protestant scholars: "Aquinas . . . has helped me to be a better evangelical, a better servant of Christ, and to better defend the faith" (Christian History, Issue 73).

All told, this "dumb ox" pulled Christianity along an important path. Though wrapped in medieval garb, many of the questions with which Thomas struggled continue to face our own generation. Forget about angels dancing on pins. The crucial questions in Thomas' age and ours are the following: What is the relation of reason and revelation? How does the scientific observation of nature fit with our faith? Since Jesus said he is the Truth, how are all other truths related to Him? Sure, sometimes Thomas' arguments rely more on Aristotelian logic than Scripture, and you might disagree with a number of his conclusions, but Thomas led the way in the integration of Christian faith and rational thought. In our day of secularism and materialism, we need all the Christian thinking we can get.

Aquinas and Thomism

The greatest of the Medieval theologians, his commonsensical philosophy, known as Thomism, undergirds much of Catholic thought. He is considered one of the doctors of the Roman Church. Yet he did not consider his knowledge something to brag about. As he pointed out, there are things about God we can take only on faith because God has revealed them to us. Not opposed to reason, they are beyond reason. "If the only way open to use for the knowledge of God were solely that of reason, the human race would remain in the blackest shadows of ignorance."

St. Thomas Aquinas was called to defend the unity of man's mind. Siger of Brabant's theology seemed to say a statement could be true in theology although false in philosophy. Aquinas won that battle. He could have become proud.

Instead, he stopped writing. What happened, according to an early biographer, was this: While saying mass on this day, December 6, 1273, the noble-minded philosopher experienced a heavenly vision. Urged to take up his pen again, he replied, "Such things have been revealed to me that all that I have written seems to me as so much straw. Now I await the end of my life."

In the 20th century, his philosophy was revised in light of modern findings. You may meet it as neo-Thomism.

|

St. Thomas Aquinas' Proofs for the Existence of God

1. From Motion:

2. From Causation:

3. From Contingency:

4. From Degree:

5. From Design: |