1. He was (sort of) an Olympian. Up through the 1948 London Olympics, the games included art competitions. Williams submitted a poem for the 1924 Paris Olympics’ poetry competition. His friend John Pellow reported that Williams received “a Diploma & Bronze Medal by the Olympic Games, but is uneasy as to what it means, how many others have received awards, so is not boasting at present.” History website Olympedia states that Ireland’s Oliver St. John Gogarty shared the Bronze Medal with France’s Charles Anthoine Gonnet, while Williams’ medal was “probably the participant’s medal.”

2. He was often ahead of his time. Even outside of Williams’ Inklings membership, Williams had many moments of forward-thinking that make Williams worth studying. Williams edited the first major English translations of Søren Kierkegaard’s work and may have been the first person in England to lecture on Kierkegaard. He was an early advocate of Dylan Thomas’ poetry. His poetry informed poets like Sydney Keyes and Philip Larkin. Furthermore, Lindop observes that Williams’ novels and plays (particularly The Devil and the Lady) explore ideas that become famous in supernatural horror decades later, such as Rosemary’s Baby.

3. He was a great poet. Most people remember Williams for his novels or Dante scholarship, but he was an accomplished poet. Throughout his life, Williams worked on a series of Arthurian poems that many scholars call the 20th-century’s most important Arthurian poetry.

4. He managed to know everybody. The Inklings were influenced by, knew, or reacted against several famous thinkers. Williams managed to know many of them. He contributed to G.K. Chesterton’s newspapers The Daily Witness and G.K.’s Weekly. He corresponded with Y.B. Yeats for the Oxford Book of Modern Verse 1892–1935. He met Dorothy L. Sayers sometime in 1943-1944, inspiring her to study Dante, which led to her translating The Divine Comedy. He also knew T.S. Eliot, who published two of Williams’ books as the editor for Faber & Faber.

5. He got along with Tolkien. Various biographies have suggested Tolkien disliked Williams. Lindop observes this impression comes from 1960s letters when Tolkien distanced himself from Williams’ legacy. Tolkien’s 1930s-1940s letters indicate he got along fine with Williams. They got along so well that Tolkien invited Williams to see his in-progress draft of Lord of the Rings, making Williams the first person to read the in-progress work in one piece.

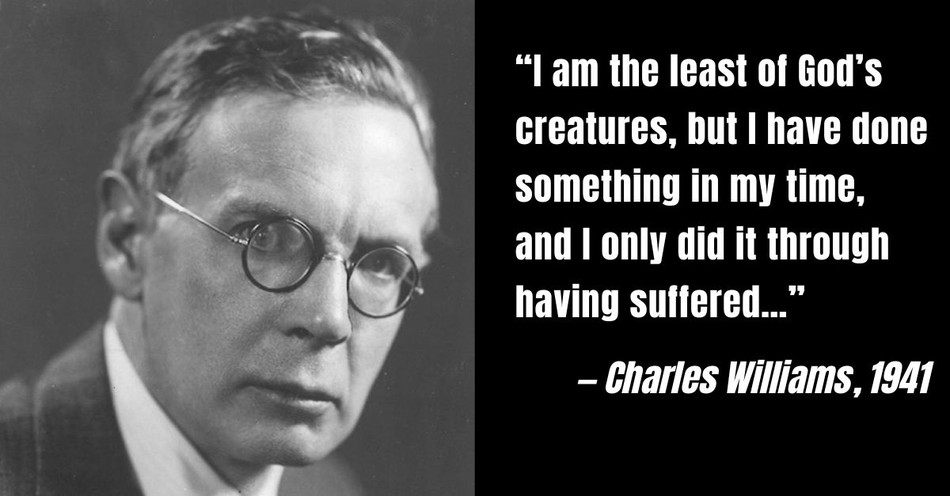

6. He had a surprising personality. Like many highly imaginative writers, Williams had highs and lows. He struggled with depression—in a 1918 letter, he admitted “wishing, as the King said in The Napoleon of Notting Hill, that God, having made the world in six days, had knocked it to bits in the next six.” Multiple friends and students describe him as awkward but with surprising warmth. W.H. Auden said after meeting Williams in 1937 that “for the time in my life, [I] felt myself in the presence of personal sanctity.”

7. He may have belonged to more than one secret society. Early books about Williams claim he joined the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn in 1917. However, records show he joined its offshoot, The Fellowship of the Rosy Cross (FRC). Lindop suggests the answer is in the middle: two years after joining the FRC, Williams began visiting Anglican vicar A.H.E. Lee to discuss “the mystical schools of all kinds.” Lee was a member of the Golden Dawn and may have inducted Williams into it.

8. He developed his own theology. Like Lewis, Williams wrote lay theology. However, Lewis aimed to restate widely held Christian beliefs in clear language. Williams made his own variations on theology, most famously an idea he called co-inherence: Christ lives in Christians, tying them to the Trinity and each other. Thus, Williams believed Christians could voluntarily carry each other’s burdens (he called this Exchange or Substitution).

9. He started a spiritual community. In 1939, Williams started the Order of the Co-Inherence, where members (or “Companions”) tried to carry each other’s burdens. For example, when Alice Mary Hadfield was traveling across the sea during WWII, Williams assigned Lois Lang-Sims to carry Hadfield’s fear of German mines in the ocean.

10. He had a dark side. Along with mystical ideas like co-inherence, Williams also believed in various spiritual exercises. Some women who sought Williams’ spiritual advice remembered him writing words on their hands or hitting their hands with a pencil. Sometimes these actions were disciplinary actions for not following spiritual exercises. Other times, they were rituals that Williams believed helped his creativity. In hindsight, these actions look like a sadistic streak that Williams didn’t face, rationalizing it with his mystic beliefs. To the extent we can understand these actions decades after Williams’ death, it provides a warning: even gifted spiritual mentors can fall prey to dark temptations.

.jpg)