Author’s note: The intention of this chapter (and the book ReGrace) is not to degrade or criticize Lewis or any other leader of the past. It's rather to show that despite his brilliance, he didn't get everything right.

Therefore, let's cut one another some slack when we encounter theological beliefs (or political beliefs) with which we disagree or find inaccurate.

Because evangelical Christians, as a whole, regard Lewis to be the greatest apologist (defender) of the Christian faith in modern history, these beliefs of his will surprise (and perhaps even shock) many evangelicals because they are regarded to be unbiblical by evangelical standards.

This being so, let's extend grace to each other whenever we disagree over theology (or politics).

--

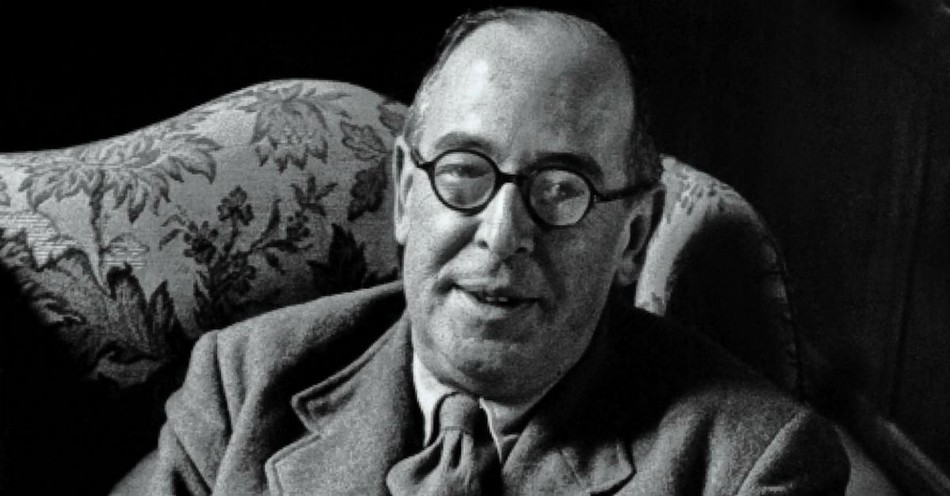

With the popularity of his Chronicles of Narnia, Mere Christianity, and The Screwtape Letters (both considered classics among evangelicals), Clive Staples Lewis is regarded by many to be a saint of evangelicalism. Christianity Today even called him “our patron saint.” According to Time magazine, Lewis was “one of the most influential spokesmen for Christianity in the English-speaking world.”

An erstwhile atheist, Lewis converted to Christianity and quickly became a renowned defender of the faith and an evangelical paragon. Lewis converted in 1931. His BBC lectures from 1942 to 1944 eventually became his book Mere Christianity (1952), establishing him as a renowned defender.

Here are a few highlights about Lewis’s life:

- He gave away a good portion of his royalties from his Christian books to those in need. This rendered him poor during his lifetime.

- He was intentional to craft handwritten responses to everyone who wrote him.

- He fought in World War I and engaged in “trench warfare.”

- Later in his life, he felt that his intellectual powers for defending the gospel had worn thin. Consequently, he felt that he was a failure as an apologist because he couldn’t persuade his closest friends and loved ones to accept the gospel.

- In his Problem of Pain, Lewis employed unassailable logic in unveiling God’s goodness and the problem of evil in the world. But when his wife passed away, he felt his earlier arguments about evil and pain were no longer adequate. His upgraded thinking on the subject appears in his later work, A Grief Observed.

Yet despite his amazing contribution to the Christian faith, here are five shocking beliefs that Lewis held.

1. Lewis believed in praying for the dead.

Here’s a quote:

“Of course I pray for the dead. The action is so spontaneous, so all but inevitable, that only the most compulsive theological case against it would deter me. And I hardly know how the rest of my prayers would survive if those for the dead were forbidden.”

2. Lewis believed in purgatory.

Springing out of his belief of praying for the dead was his belief in purgatorial cleansing. According to Roman Catholic dogma, purgatory is the final purification of the elect after death.

In A Grief Observed, Lewis talked about his deceased wife, Joy, connecting her to suffering and cleansing in purgatory.

Lewis believed in salvation by grace, but he thought complete transformation was dependent upon one’s choice. Thus he felt that transformation can even occur after death, and some Christians need to be cleansed in order to be fit for heaven and enjoy it.

For Lewis, purgatory was designed to create complete sanctification, not retribution or punishment. So Lewis saw purgatory as a work of grace.

Here are some revealing quotes from Lewis:

To pray [for the dead] presupposes that progress and difficulty are still possible. In fact, you are bringing in something like Purgatory. Well, I suppose that I am. Though even in Heaven some perpetual increase of beatitude, reached by a continually more ecstatic self-surrender, without the possibility of failure but not perhaps without its own ardours and exertions—for delight also has its severities and steep ascents, as lovers know—might be supposed. But I won’t press, or guess, that side for the moment. I believe in Purgatory.

3. Lewis believed that it was possible for some unbelievers to find salvation after they have left this world.

While Lewis didn’t subscribe to universalism or ultimate reconciliation, he did believe that salvation after death was a possibility for some. His view was that some people may seek and find Christ without knowing Him by name. However, he was very clear that this was not “salvation by sincerity” or “goodness” but rather a Spirit-driven desire for God.

For Lewis, Christianity is not the only revelation of God’s way, but it is the complete and perfect revelation. Lewis, therefore, didn’t hold to the idea that all roads lead equally to God. In addition, Lewis believed that time may not work the same way after death as it does in life. Thus all those who lived before Christ and after might be subject to the grace of repentance.

Interestingly, Lewis’s distant mentor, George MacDonald, believed in ultimate reconciliation (meaning, hell will be empty because God will win everyone to Himself in the end). Lewis’s regard for MacDonald was incomparable. He said of MacDonald, “I dare not say that he is never in error; but to speak plainly I know hardly any other writer who seems to be closer, or more continually close, to the Spirit of Christ Himself.” That’s quite a statement to make about someone you don’t fully agree with doctrinally.

4. Lewis believed that it was acceptable for Christians to drink alcohol.

In contrast, many evangelicals today believe that all Christians should abstain from alcohol. Here’s a direct quote by Lewis on this point: Temperance is, unfortunately, one of those words that has changed its meaning. It now usually means teetotalism…It is a mistake to think that Christians ought to be teetotalers; Mohammedanism, not Christianity, is the teetotal religion.

5. Lewis didn’t believe that all parts of the Bible were equally the Word of God.

In his Reflections on the Psalms, Lewis made these interesting comments:

"Speaking of judgment and hatred in the Psalms. [Lewis calls them, “the vindictive Psalms, the cursings”; they are also known as “the imprecatory Psalms.”] Yet there must be some Christian use to be made of them; if, at least we [Christians] still believe (as I do) that all Holy Scripture is in some sense—though not all parts of it in the same sense—the word of God.”

Frank Viola has helped thousands of people around the world to deepen their relationship with Jesus Christ and enter into a more vibrant and authentic experience of church. His mission is to help serious followers of Jesus know their Lord more deeply, so they can experience real transformation and make a lasting impact. Viola has written many books on these themes, including his groundbreaking 2018 book Insurgence: Reclaiming the Gospel of the Kingdom. His blog, frankviola.org, is rated as one of the most popular in Christian circles today.