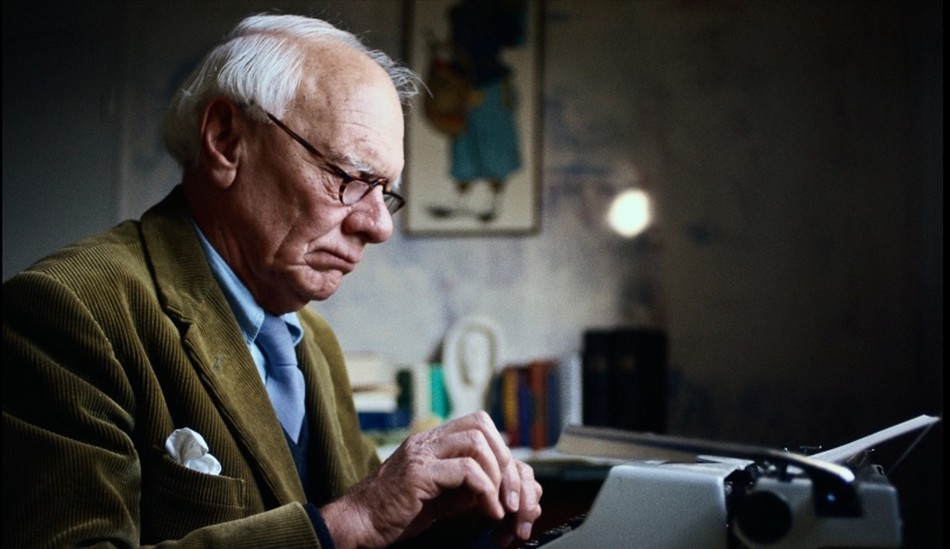

Few twentieth-century Christian writers captured the spiritual journey’s complexities like Malcolm Muggeridge. Biographer Gregory Wolfe describes Muggeridge spending nights partying, then reading Christian mystics when he got home. Muggeridge embraced Christianity publicly around the time he made Mother Teresa famous, but he never lost his love of heckling religious hypocrites. He used his TV celebrity platform to criticize sinful living, but freely admitted his lifestyle had many flaws. Like C.S. Lewis, he is remembered for defending the Christian faith, but perhaps in a quirkier way.

Muggeridge’s penchant for swimming against the stream has important lessons for today. Sometimes he trailblazed—this year marks 90 years since he reported Soviet atrocities in Ukraine. Other times, he came across as a grumpy contrarian—his position as an early TV celebrity allowed him to ruffle many feathers. Both his strengths and his weaknesses can teach Christians about living a countercultural life wisely.

10 Important Events in the Life of Malcolm Muggeridge

1. Muggeridge was born March 24, 1903, in Croydon, South London. His father was an outspoken socialist writer and politician who hoped his son would continue in his tradition.

2. In 1920, Muggeridge entered Cambridge University. During this period, he began to take Christianity seriously and met his lifelong friend, future theologian Alec Vidler.

3. In 1927, Muggeridge returned to England after two years of teaching in India. The same year, he married Kathleen “Kitty” Rosalind Dobbs, who became a successful writer in her own right. Their first child, Leonard, was born in 1928.

4 In 1932, Muggeridge moved to Moscow. He submitted reports on Holodomor, a man-made famine in Ukraine caused by the Soviets changing farming systems and punishing Ukrainians for resisting change. He was one of the first Westerners to report the famine, which killed over three million, while many denied it was happening.

5. In 1938, Muggeridge published one of his best books: In a Valley of this Restless Mind, an autobiographical novel describing his spiritual journey to that point.

6. In 1948, the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) offered Muggeridge to appear on the radio show The Critics. He would continue contributing to the BBC as a journalist and commentator for decades.

7. In 1954, Muggeridge interviewed Billy Graham for the TV show Panorama, kickstarting his most famous role as a TV interviewer.

8. In 1957, not long after leaving his job editing satire magazine Punch, Muggeridge published an article in the Saturday Evening Post criticizing media treatment of England’s royal family, saying it reduced them to a “royal soap opera.” Outrage led to the BBC temporarily banning him.

9. In 1969, Muggeridge interviewed Mother Teresa for a documentary that catapulted her to worldwide fame. The same year, he published Jesus Rediscovered, the first of several books about key figures of Christianity.

10. In 1982—which William F. Buckley observed was 26 months after their TV interview that Muggeridge suggested should be called “Why I Am Not A Catholic”—Muggeridge was received into the Roman Catholic church. Six years later, he published his autobiography, Conversion.

10 Great Quotes by Malcolm Muggeridge

1. “Ever after, being at Cambridge and certainly in India later teaching at the Christian college there, I felt myself to be a Christian. But not a good one. A bad one.

Did you ever get to the point where you felt you were a good one?

No… no, I’m afraid not. But I’m better than I was.” — interview with David Porter

2. “It was accompanying Mother Teresa in Calcutta to the scene of the various activities of her Missionaries of Charity… that I came nearest to understanding for a moment what Jesus meant by feeding his sheep.” — unpublished reflection included in The Very Best of Malcolm Muggeridge

3. “I think [satire] is important in exactly the same way, has exactly the same role, that the Fool had in Shakespeare’s plays… [he] points out that the emperor is naked, because the emperor always is naked. Power is always absurd.” — interview included in St. Mugg: A Portrait of Malcolm Muggeridge

4. “The prophets, when they appear on our earthly scene, are rarely expected.” — The Third Testament

5. “There is no occupation more wretched than trying to make the English laugh.” — comment on the show Desert Island Discs about his period editing Punch.

6. “Had I been a journalist there I should, I am sure, have spent my time hanging about King Herod’s palace, following the comings and goings of Pilate, trying to find out what was afoot in the Sanhedrin; the cameras would have been set up in Caesarea, not Galilee, still less on Golgotha.” — Christ and the Media

7. “Never forget that only dead fish swim with the stream.” — an homage to a GK Chesterton quote

8. “The Devil is a very big and clever person, particularly in New York. And he fools many New Yorkers by convincing them they are very smart.” — conversation with George J. Marlin

9. “The prayer which really comprises all other prayers is the phrase in our Lord’s prayer: ‘Thy will be done.’ All that one can want in life is that God’s will be done.” — interview with David Porter

10. “The appeal of Christianity, as I understand it, is that it offers man something beyond this world. It says to him that he must die in order to live, an extraordinary proposition to put before him. It tells him that he can never create peace or happiness for himself merely by perfecting his circumstances on earth. It presents him, in other words, as a creature who intrinsically requires salvation. Now it would seem to me that the churches and those who present the Christian religion to us have moved entirely away from this attitude, and increasingly tell us that it is possible to make terms with this world.” — essay “Am I a Christian?” included in Vintage Muggeridge

What Can We Learn from Malcolm Muggeridge?

1. Don’t be afraid to be different. Muggeridge took unpopular sides throughout his life. Early in his career, he horrified his leftwing family (and Kitty’s family) when he reported that communists were causing a famine in Ukraine. Taking a stand for what’s right may mean great sacrifice and embarrassment.

2. Humor can hurt, but that can be a good thing. Muggeridge was involved in several controversies where he satirized things people respected. His insights frequently proved correct. His satire could cut, but it exposed people’s sacred cows.

3. Don’t be afraid of the journey. While Muggeridge considered becoming a priest during his university years, it was decades before he fully accepted Christianity. Os Guinness recalls in his book Fool’s Talk that Muggeridge told him he’d spent years figuring out what he believed, but he always knew what he disbelieved in. Sometimes the spiritual journey begins small and takes a while.

4. Sometimes, what’s good is for the moment. Muggeridge became most famous as a TV personality, which means some of his best work is forgotten—yesterday’s TV doesn’t interest many viewers today. However, Stephen C. Board writes in The Practical Christianity of Malcolm Muggeridge that his work served its purpose: “Television could probably not market a second Muggeridge, but our generation has desperately needed one of them.”

5. Don’t make difference into an idol. While Muggeridge often took unpopular sides for good reasons, sometimes he took unpopular sides just to be contrary. This could backfire, as in 1979 when he debated members of Monty Python about a movie that he apparently hadn’t seen fully. There is a line between being countercultural and being foolish.

6. Don’t be afraid of doubt. Even after embracing Christianity and making his faith public, Muggeridge didn’t pretend he had no struggles or questions. His writings about Christianity often contain him admitting the Christian doctrines he still wonders about. Being honest about one’s doubts enables a search for answers, and a willingness to admit when the answers prove complicated.

7. Don’t be afraid of mystery. While Muggeridge took his time before making a public commitment to faith, he always liked the Christian mystics. It’s not a bad thing for faith to contain poetry and mystery.

8 Don’t forget to help others. While Muggeridge wasn’t enough of a follower to become a formal mentor, he did influence other Christians. Guinness, Steve Turner, and others recalled advice he gave them about faith, writing, and apologetics.

9. Talented people can have feet of clay. Muggeridge had a reputation as an aggressive womanizer—something he admitted, and which he slowly overcame after becoming a Christian. Today, he would likely be classified a sex addict who didn’t break the cycle until years after finding faith. However, recognizing someone has an addiction doesn’t make the behavior right. Today, as many Christians discuss sexual misconduct more openly, Muggeridge’s behavior forces us to realize such situations are always complex. Not everyone who becomes a Christian immediately changes their lifestyle around. Talented Christians can behave wisely or horribly.

10. Forgiveness and rebirth may happen when we least expect it. Muggeridge’s marriage proved to be a complicated one. He and Kitty began married life as secular freethinkers who didn’t believe in monogamy. The situation led to a great deal of hurt—he had many escapades, and they raised a son that Kitty had through an affair. Over time their values changed, and friends and neighbors reported they had a loving marriage.

10 Best Muggeridge Books

1. Like It Was: The Diaries of Malcolm Muggeridge. Less varnished than Muggeridge’s memoir Chronicles of Wasted Time, this book gives a deeper look at his life.

2. Winter in Moscow. One of Muggeridge’s early novels, based on his time in Russia.

3. Tread Softly For You Tread on My Jokes. A collection of Muggeridge’s journalism, from essays on humor to his memories of meeting MI6 traitor Kim Philby.

4. Something Beautiful for God. Muggeridge’s profile of Mother Teresa played a huge role in her becoming a saint, Nobel Peace Prize winner, and one of the twentieth century’s most famous women.

5. The Thirties: 1930-1940 in Great Britain. An insightful look at the decade leading up to World War II, its follies, and how Hitler and Mussolini looked when the war started.

6. Affairs of the Heart. A murder mystery thriller that parodies the genre a little, the story follows a journalist hired to write a biography of a deceased mystery author… which may involve solving mysterious death.

7. Jesus: The Man Who Lives. A compelling look at whether Jesus still has relevance in the modern age, and what that means for spiritual searchers.

8. In A Valley of This Restless Mind. An entertaining Pilgrim’s Progress-style look at Muggeridge’s early travels through different worldviews.

9. A Third Testament. A collection of profiles on inspiring Christian figures, from Fyodor Dostoevsky to Dietrich Bonhoeffer.

10. Conversion: The Spiritual Journey of a Twentieth Century Pilgrim. Muggeridge’s autobiography starts with the date he and Kitty become Roman Catholics, then looks back at his life—from miracles he’s convinced he experienced while interviewing Mother Teresa to his early spiritual hunger.

You can also find his work collected in anthologies like Time and Eternity: Uncollected Writings and Seeing Through the Eye: Malcolm Muggeridge on Faith. Readers can learn more about his life in the biographies written by Gregory Wolfe, Richard Ingram, and Ian Hunter.

Photo Credit: Getty Images/Pennie Tweedie

This article is part of our People of Christianity catalog that features the stories, meaning, and significance of well-known people from the Bible and history. Here are some of the most popular articles for knowing important figures in Christianity:

How Did the Apostle Paul Die?

Who are the Nicolaitans in Revelation?

Who Was Deborah in the Bible?

Who Was Moses in the Bible?

King Solomon's Story in the Bible

Who Was Lot's Wife in the Bible?

Who Was Jezebel in the Bible?

Who Was the Prodigal Son?