Perseverance: "Be Like Libby"

George Carver's eyes widened as he untied the paper wrapping and took out the worn leather Bible. "A Christmas present for me?" he said in surprise.

"For when you learn to read," said the kindly midwife. Mariah Watkins had seen the fourteen-year-old boy sitting on her fence earlier that fall of 1875, looking hungry and lost. He'd walked to Neosha, Missouri, to attend the Lincoln School for Colored Children—but he had no money or a place to live. The Watkinses had taken him in and were amazed at how hard he worked for his keep. The boy had promise.

"Do you know how to read, Aunt Mariah?" George asked.

Mariah's eyes got misty. "Before the Civil War, I was a slave, just like your mammy. Of all the slaves on the plantation, only one, a woman named Libby, knew how to read. If our master had found out, she probably would've been sold down river to the South quick as a blink, because any slave who had some learnin' was considered uppity and dangerous. But Libby refused to keep this gift to herself and secretly taught some of us how to read." Mariah took the boy by the shoulders. "George, you must learn all you can, then be like Libby. Go out in the world and give your learnin' back to our people. They're starvin' for a little learnin'."

George was eager to learn and began reading the Bible, a daily habit that gave him strength to the end of his life. But he soon learned everything the Neosha teacher could teach him. Hitching a wagon ride to Fort Scott, Kansas, he got a job cooking to earn money for school books. But one day he saw a black man dragged out of jail and burned to death by an angry mob. Frightened, he realized it was dangerous to have dark skin in Fort Scott.

Traveling from town to town in the Midwest, doing odd jobs, George finally graduated from high school. He excelled in botany, biology, chemistry and art—but there was so much more to learn! Hardly daring to hope, he applied to a Presbyterian college in Highland, Kansas. One day the longed-for letter arrived: He had been accepted! That fall he eagerly arrived on campus. But the dean took one look and said, "You didn't tell us you were a Negro. Highland College does not take Negroes."

George was devastated. Was this the end of the road for him?

A few years later, renewing his courage, he applied to Simpson College and was accepted—only the second black person in the college's history. At his art teacher's urging, he transferred to the Iowa State College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts to study horticulture—even though he was barred from the student dining room and had to eat with the kitchen staff. He suffered this indignity patiently, telling himself that ignorant people would not keep him from his duty. The school quickly changed its mind when a prominent white woman who admired George's paintings came to visit him and insisted on eating with him in the kitchen.

After obtaining his master's degree, George was offered a job as professor at Iowa State. But in his mind he heard Mariah Watkins' voice saying, "Be like Libby. Give your learnin' back to your people." When a letter from Tuskegee Institute in Alabama arrived, asking Professor Carver to come teach southern blacks new ways to farm, he knew immediately this was the task God had been preparing him for all along.

Resourcefulness: Most Weeds Have a Purpose

"I cannot offer you money, position, or fame," Booker T. Washington had written to George Carver. "I offer you in their place work—hard, hard, work—the task of bringing a people from degradation, poverty, and waste to full personhood."

As Dr. Carver, satchel in hand, stood looking at the dreary frame buildings and barren, dusty grounds of the Tuskegee Institute, Washington's words took on grim meaning. The soil was starving, drained of its nutrients by centuries of planting cotton, only cotton. But some things were growing here and there. Curiously, Carver set down his bag and began picking this leafy stalk, then that one, until he had an armful.

"Lad," he called to the boy who had picked him up from the train, "what is the name of this plant?"

"That?" said the boy. "It's a weed."

"They're all weeds." Carver smiled. "But every weed has a name, and most of them have a purpose."

Within a few weeks, Professor Carver had thirteen students and a task: to set up a laboratory to test local soil and find ways to enrich it for farming. Only one hitch; there was no money to buy equipment for a laboratory.

Carver had never let the lack of money stand in his way. God had given him a brain, and he intended to use it. Marching his students to the school dump, he directed them to save everything useful: bottles, cooking pots, jar lids, wire, odd bits of metal, rusty lamps, broken handles. When the dump had been thoroughly searched, they scoured the back alleys of Tuskegee for china dishes, rubber, curtain rods, and flat irons.

"All this may seem like junk to you," he told his skeptical students. "But it is only waiting for us to apply our intelligence to it. Let's get to work!"

Under Carver's supervision, the students punched holes in pieces of tin to make strainers to test soil samples. Neatly labeled canning jars held an assortment of chemicals; broken bottles were cut down and transformed into beakers; a discarded ink bottle with a cork and a piece of string made do nicely as a Bunsen burner.

Gradually the makeshift laboratory took shape. And a valuable lesson was learned by the Tuskegee students that carried over into later years, when they took their knowledge into the poverty-stricken pockets of the South. Expensive or brand-new equipment was not a requirement for success.

Dr. Carver was never satisfied with only the obvious use of a thing, especially when it came to things in nature. He firmly believed God had provided all that people needed in the created world; God left it to humans to figure out the secrets locked within each plant, animal, or mineral. To many, a peanut was just a snack and not worth growing as a crop. But with Dr. Carver's probing curiosity and scientific knowledge, the peanut produced butter, oil, milk, dye, salve, shaving cream, paper, shampoo, metal polish, stains, adhesives, plastics, wallboard, and more—for a total of three hundred products! It was this variation that provided new markets for southern crops and saved the South from ruin.

Make It Real! Questions to help you dig a little deeper and think a little harder.

1. What were some of the obstacles George faced that would have made the average person give up the idea of getting an education?

2. In what ways was Dr. Carver resourceful? How can you be more resourceful with the things God has given you? How is being resourceful a good way to care for God's creation?

3. George's favorite Bible passage was Psalm 121:1-2: "I lift up my eyes to the hills—from where will my help come? My help comes from the Lord, who made heaven and earth." (NRSV) Why do you think this passage is so fitting for the life he led?

4. You will find some of Dr. Carver's peanut recipes (soup, bread, candy and more) at http://aggie-horticulture.tamu.edu/plantanswers/recipes/peanutrecipes.html

Suggested reading:

1. Hero Tales Vol. III by Dave and Neta Jackson (Bethany House Pub., a division of Baker Pub. Group, 1998).

2. George Washington Carver, From Slave to Scientist by Janet and Geoff Benge (Heroes of History, Emerald Books)

3. The Forty Acre Swindle by Dave and Neta Jackson Jackson (Trailblazer Books, Bethany House)

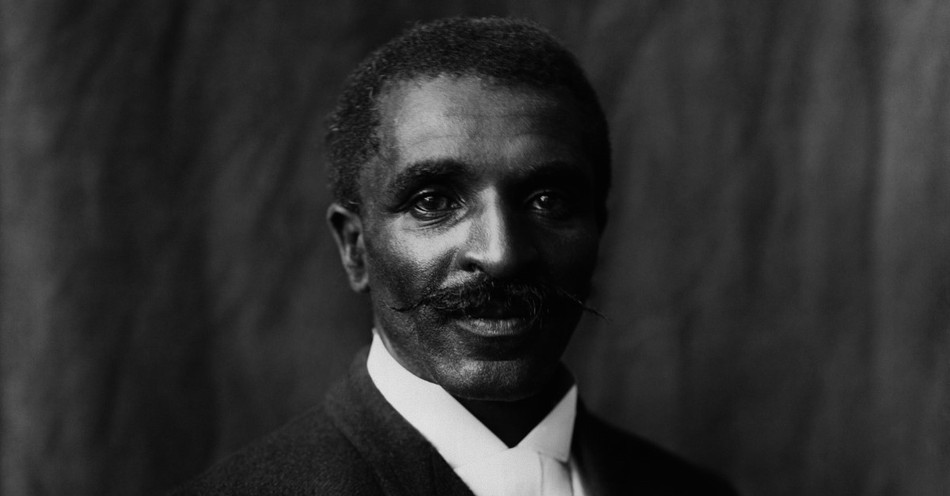

Photo Credit: Public Domain Picture via Wikimedia Commons/Library of Congress

(Article first published on Christianity.com on July 19, 2010)

This article is part of our People of Christianity catalog that features the stories, meaning, and significance of well-known people from the Bible and history. Here are some of the most popular articles for knowing important figures in Christianity:

How Did the Apostle Paul Die?

Who are the Nicolaitans in Revelation?

Who Was Deborah in the Bible?

Who Was Moses in the Bible?

King Solomon's Story in the Bible

Who Was Lot's Wife in the Bible?

Who Was Jezebel in the Bible?

Who Was the Prodigal Son?