Who was David Livingstone?

When someone asked David Livingstone why he became a missionary to Africa, he replied, "I was compelled by the love of Christ." A medical doctor, missionary, preacher, African explorer, humanitarian, and fighter against the slave trade, David Livingstone went fearlessly to places other outsiders had never gone and, from the obscurity of the remote African interior, became one of the most celebrated heroes of his era.

Born into a poor family of five children in Blantyre, Scotland, young David went to work at age 10. After working a 14-hour day at a cotton factory spinning jenny, he would go to night school for two more hours. With his first week's wages, he bought a Latin text and propped it on his machine so he could study while working.

Before he was 21, he had committed his life to Christ as a medical missionary. He studied medicine and theology in Glasgow, and at 27 he was sent by the London Missionary Society to South Africa as both a doctor and an ordained minister. Arriving in l841 he trekked north 600 miles to Kuruman, thus beginning a life of walking that would take him more than 29,000 miles back and forth across Africa's vast interior. At Kuruman, he served in the station of the noted missionary Robert Moffat.

Once, when natives at the mission were losing cattle to lions, Livingstone fired on an attacking male lion which "caught me by the shoulder as he sprang, and we both came to the ground together. Growling horribly close to my ear, he shook me as a terrier does a rat." Distracted by the natives, the lion suddenly fell over dead from the bullet that had found its mark. Livingstone carried the lion's tooth scars on his shoulder the rest of his life. After his recovery, he married Moffat's daughter, Mary, with whom he would eventually have six children.

Finding His Calling

For the next 10 years, Livingstone was a traditional missionary. He wrote enthusiastically: "I am a missionary... In this service I hope to live; in it, I wish to die." But Livingstone soon found God leading him in a different direction. Frustrated over lack of converts, and after several failed efforts to set up mission stations, he concluded that God's purpose for his life was to use his talents to explore and map the vast African heartland -- to open up "God's Highway" which would bring "Christianity, commerce, and civilization" and put an end to the Arab slave trade.

In l852, after sending his wife and children to England, Livingstone started exploration, becoming the first European to go across Africa from West to East. It was on this trip that he discovered what the natives called mosi oa tunya – “The smoke [mist] that roars” where the Zambezi plunges over the edge of a huge fissure in the earth to form one of the world's most beautiful spectacles. He named it Victoria Falls after British Queen Victoria. Returning to a hero's welcome in England in l856, Livingstone was given an audience with Queen Victoria. She laughed when he told her of the African chief who, in trying to estimate her wealth, had asked: “How many cows does she have?”

In l857, Livingstone withdrew from the London Missionary Society due to honest differences over whether a missionary should stay in one place or should be allowed to travel and explore. In the same year, Livingstone published Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa and somewhat later Narrative of an Expedition to the Zambezi and its Tributaries. The next year, he launched his ill-fated Zambezi Expedition. The plan was to go upriver in a steamboat, The Ma Robert, and establish a mission above Victoria Falls. Everything went wrong. Livingstone's wife and others died on the trip, the steamboat leaked and was finally blocked at a 30-foot waterfall. Livingstone changed plans, sailing up the Shire River to Lake Nyasa until England terminated the expedition.

Search for the Source

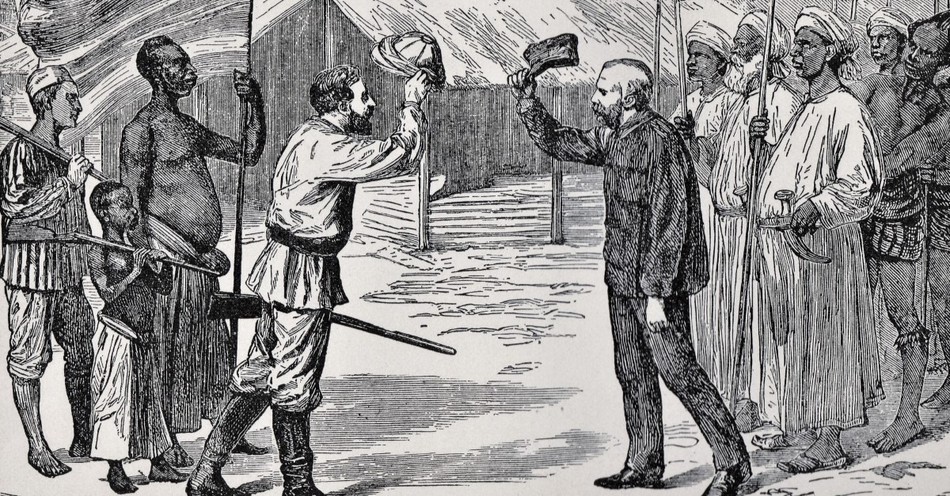

In 1858, the Royal Geographical Society sent Livingstone to find the source of the Nile. Three years earlier, explorer John Speke had reported the source was Lake Victoria [he was right]. But Livingstone and the Society believed other lakes to the south had outlets flowing north into Lake Victoria. At age 52, Livingstone set sail for Africa on what was to be his last journey. He started inland with 60 porters, most of whom quickly deserted him. He pressed on, searching without success for 7 years. By 1871, Livingstone had reached the Lualaba River, headwaters of the Congo, which he mistakenly thought to be the Nile. At Nyangwe he saw Arab slave traders massacre between 300 and 400 Africans. Sick at heart and in the body, he retraced his steps to Ujiji on Lake Tanganyika. For almost five years the world had not heard from him. Then, the New York Herald sent Henry Stanley, a tough journalist, to find him and the story.

On November 10, l871, Stanley marched into Ujiji, and when the famous explorer came out to meet him, Stanley responded with what has become one of history's most famous greetings: “Dr. Livingstone, I presume?” Refreshed with medicine and supplies, Livingstone became Stanley's close friend but refused to return to the coast with him, saying his work was not done. In 1872, newly outfitted with over 50 porters sent from the coast by Stanley, Livingstone set out once again to find the Nile's source, but he became so weak he had to be carried on a litter. One morning, aides found him dead in his grass hut, kneeling in prayer by his bed. His faithful porters buried his heart at the foot of a giant tree, mummified his body, and carried it for nearly 1,000 miles to the coast, then sailed for London. There his remains were easily identified by the old lion wound on the shoulder. He was entombed in Westminster Abbey where his epitaph reads:

Brought by faithful hands over land and sea, here rests David Livingstone, missionary, traveler, philanthropist, born March 19, 1813, at Blantyre, Lanarkshire, died May 1, 1873, at Chitambo’s village, Ulala. Other sheep I have which are not of this fold; them also I must bring (John 10:16).

An Amazing Influence

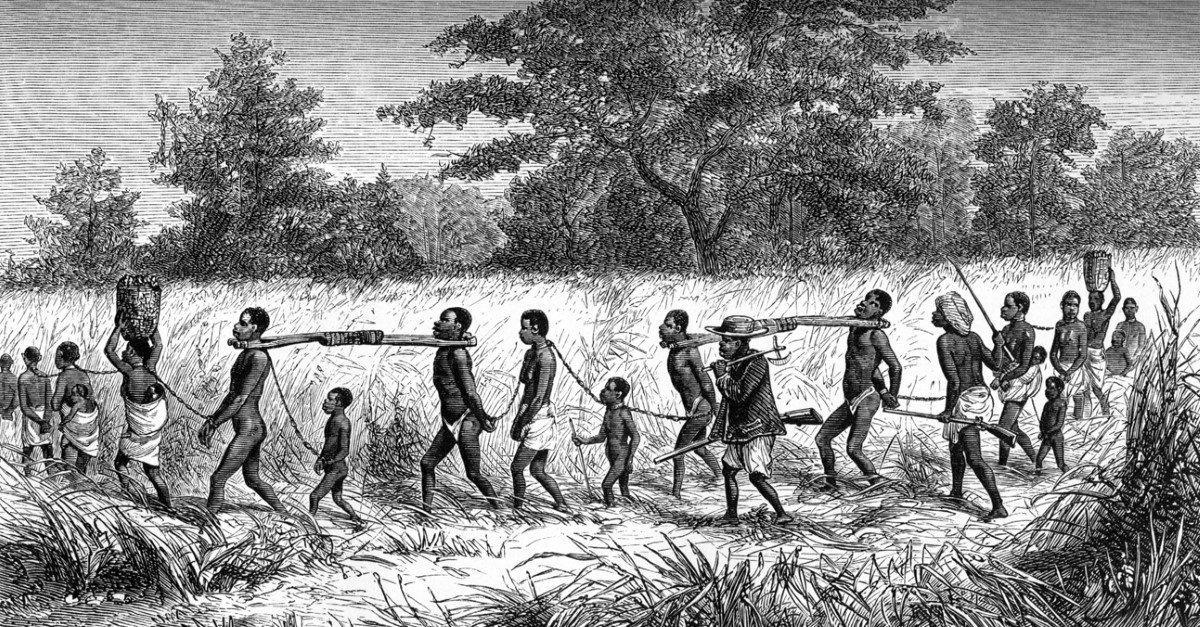

Livingstone's example has inspired tens of thousands of Christians everywhere and influenced hundreds more to become missionaries. Famous gospel pioneers such as Alexander Mackay (Uganda), Melvin Fraser (Cameroon), Mary Slessor (Nigeria), were all touched by Livingstone's life and led to follow his trails. But the world is equally indebted to Livingstone for his relentless attack on slavery. He was the first European to traverse the interior where he constantly passed slave caravans of up to 1,000 slaves tied together with neck yokes or leg irons, carrying ivory or other heavy loads, marching single file 500 miles down to the sea. Men or women slaves who complained about their load were promptly speared to death and left by the wayside. One could trace the trail of a slave caravan by the vultures and hyenas that feasted on the corpses it left behind. Livingstone wrote of the slave trade: To overdraw its evils is a simple impossibility... We passed a woman tied by the neck to a tree and dead... We came upon a man dead from starvation... I passed a slave woman shot or stabbed through the body... The strangest disease I have seen in this country seems to be broken heartedness, and it attacks free men who have been captured and made slaves. Livingstone estimated that 80,000 died each year, during capture or on the journey from the interior before ever reaching the auction blocks of Zanzibar. Once, after walking 120 miles near Lake Nyasa, he was shocked not to see a single human being, so thoroughly had the land been depopulated by the slave trader whom he described as "a monster brooding over Africa."

A Dream Fulfilled

Livingstone's personal and public letters, combined with those of other missionaries, ignited a public outcry for Parliament to stop the slave trade on the high seas. When Livingstone parted with Stanley, he sent a letter to be published describing the massacres of Africans by Arab slave traders at Nyangwe. He said that if his writings should lead to the suppression of the terrible Ujijian slave trade: "I shall regard that as a greater matter by far than the discovery of all the Nile sources together." This fondest dream of Livingstone was indeed realized. Although he never found the source of the Nile, his ongoing journalistic attack of the slave trade had begun to bear fruit even before his death. In 1871, Livingstone's and others' antislavery protests spurred the House of Commons to action. A month after Livingstone died, England threatened a naval blockade of Zanzibar which forced the Sultan to close its slave market forever.

Livingstone's Example Continues to Influence

This issue of Glimpses was primarily written by Dr. Gordon Severance and provides another example of how a love of Christian history radically affects one's practical Christian life. Dr. Severance is the husband of Dr. Diana Severance, a regular writer for Glimpses. This near eighty-year-old retired lawyer is a marvel! Co-author of a standard college textbook on business law, Severance has devoted his retirement years to advancing Christian missions. Christian History Institute is indebted to him as he was the one who goaded, gave his time sacrificially, and muscled us into sticking with the most difficult project we ever undertook, our full-length film drama, Candle in the Dark, on the life of William Carey, the “Father of Modern Missions.” Severance served on this film as everything from errand boy, fundraiser, international diplomatic negotiator, executive producer-India, to premiere showings organizer. His mother, raised in Turkey by missionary parents, read to him about David Livingstone when he was a small boy. He never forgot the movie on Livingstone that he saw as a youth with Spencer Tracy and Frederick March as lead actors. His father had Stanley's In Darkest Africa in his library, which Gordon devoured as a youth.

It was Severance who was chosen to go to Uganda to teach constitutional law as a Fullbright scholar at Makerere University in Kampala and to advise the Ugandan Constitutional Commission in their drafting of a new constitution that would avoid the tragic perversions of their former leader and one of history's worst despots, Idi Amin. During that tenure in Africa, as well as on his other trips there, Severance would study and follow the journeys of Livingstone, including rafting down the Zambezi river. He also scaled Mt. Kilimanjaro (19,300 feet). But legal beagle Severance (who some of our staff at Christian History Institute affectionately refer to as our "Texas Tiger" -- as he now lives in Texas and loves tigers) did more than study. He considered that if Livingstone in his day could build medical clinics to serve African people, then why couldn't he today? He selected a location where only shortly before Idi Amin and Milton Obote's men had massacred between 500,000 and 800,000 men, women, and children and there built a nearly 2,000 square foot clinic to minister to the needy population. That clinic has now treated over 30,000 people and delivered over 5,000 babies. Severance ponders: "How pleased Livingstone must be to see the fruit of his Christian influence in the schools, churches, and, yes, even the clinics like this one in his beloved Africa."

A Ready Worker

Young David Livingstone was such a faithful and valued worker in the cotton mill that his employer agreed to let him work six months and then attend medical school six months.

In his explorations, Livingstone was expert at "shooting the sun" to determine his geographical longitude and latitude, and on his explorations always sketched detailed maps --he was the "Kit Carson" of Africa.

Further Reading:

David Livingstone: Explorer, Missionary and Abolitionist

(Article first published on Christianity.com on April 28, 2010)

Photo Credit: Getty Images/Christine_Kohler

This article is part of our People of Christianity catalog that features the stories, meaning, and significance of well-known people from the Bible and history. Here are some of the most popular articles for knowing important figures in Christianity:

How Did the Apostle Paul Die?

Who are the Nicolaitans in Revelation?

Who Was Deborah in the Bible?

Who Was Moses in the Bible?

King Solomon's Story in the Bible

Who Was Lot's Wife in the Bible?

Who Was Jezebel in the Bible?

Who Was the Prodigal Son?