Why Did C.S. Lewis Call Jesus a True Myth?

To the modern person, a myth is defined as something false. Mythology is often viewed as interesting stories conveying some moral message but primitive superstition. C.S. Lewis rejected this view of myth. He believed that God, the great storyteller, revealed Himself through different mythologies throughout history. He also believed that these myths’ core ideas were fulfilled in the first century through Jesus of Nazareth’s incarnation, death, and resurrection.

Let’s look at what led C.S. Lewis to this perspective on myth.

SPECIAL OFFER: Enroll in this free online course on C.S. Lewis today!

How Did C.S. Lewis Define a Myth?

Before my conversion from agnosticism to Christianity, I thought myths were interesting tales but still lies, with nothing true in them. Reading C.S. Lewis led me to reject this view and understand myth’s cultural and spiritual importance. To an ancient mind, a myth was a story that conveyed an important universal truth about what it means to be human. This is rather difficult for a modern person to understand. Our culture has been heavily influenced by what Lewis called chronological snobbery—if it doesn’t fit how we think about things today, it can’t be true.

Our culture has also fallen prey to assuming that only the things we can prove are true. The fact is we constantly learn how little we know. We also find that myths never die. The popularity of Marvel and DC films and comics, the writings of fantasy authors like Neil Gaiman, J.K. Rowling, and Madeleine L’Engle—all these examples are inspired by mythology in some way.

C S. Lewis viewed myth as the ancients did. Through the power of myth, he went from being a staunch atheist to bowing the knee to Christ.

How Did Mythology Help Lewis Become a Christian?

The friendship between J. R. R. Tolkien and C. S. Lewis is legendary, and their long conversation on a fine windy night on September 19, 1931, is also legendary.

Lewis and Tolkien were walking along Addison’s walk with their friend Hugo Dyson. Dyson, like Tolkien, was a devout Christian and academic who made a strong impression on Lewis when they first met. Lewis found it odd and comical that some of his closest friends among the Oxford faculty held a very different worldview from his atheism.

Addison’s walk is a beautiful path at Magdalen College in Oxford, England, named after Joseph Addison, a fellow of Magdalen College. It plays a crucial role in understanding the conversation about myth that changed Lewis’s life. To this day, many people travel from all over the world to walk the path and reflect on what the conversation must have been like between these three incredible writers.

As the three friends walked, their conversation ranged from science to poetry to religion. Lewis conveyed his love for myth to his friends and his materialistic view that as delightful as myths are, they are still lies.

Tolkien pointed out to Lewis the limitations of his staunch rationalism. Tolkien helped Lewis understand that these mythic stories about gods convey an innate human yearning for meaning and redemption. Furthermore, some myths’ themes foreshadowed what happened in the Christian story. Tolkien suggested to Lewis that there was a special reason that Lewis enjoyed the ancient death and resurrection pattern in many stories about gods. For example, in Norse myth, the trickster god betrays Odin’s son Balder, who dies but is predicted to rise again when Ragnarok arrives—a time when the earth is destroyed, and a new heaven and new earth are formed. Similar stories appear in Greek myth (Adonis and Bacchus) and Egyptian myth (Osiris)

Tolkien argued that Lewis loved dying and rising god stories because they have something true in them. When Jesus of Nazareth appeared in the first century, died and rose again, he fulfilled all the good things those myths had foreshadowed. Jesus was a myth that came true.

This proved to be a changing point in the conversation and a key part of Lewis accepting theism. He wouldn’t become a full-fledged Christian until later—after a motorcycle ride with his brother Warnie. Still, the conversation with Dyson and Tolkien brought an important change. Lewis gave up his limited empirical view, making an important step toward accepting Christ’s agape love after he had resisted for many years.

How Can Jesus Be a “True Myth”?

In Lewis’ terms, the historical incarnation, death, and resurrection of Christ in the first century can be called a true myth. It fulfills the deep human longing for redemption present in many cultures’ death and resurrection stories. The Creator of time and space chose to convey truths to these cultures of what was to come, placing His agape love on display for all of humanity through Jesus’s remission of sins, the defeat of death and the powers of Hell, and offer of hope and eternal life to everyone. Christ is the source of goodness, beauty, poetry, and truths conveyed in myth. When I came to understand this by reading Lewis’s wonderful essay “Myth Became Fact,” it was a revelation to me. If God can speak through Balaam’s donkey, he can reveal Himself through different myths, poetry, and stories. I find these lines from “Myth Became Fact” to be incredibly poignant:

“Now as myth transcends thought, incarnation transcends myth. The heart of Christianity is a myth which is also a fact. The old myth of the dying god, without ceasing to be myth, comes down from the heaven of legend and imagination to the earth of history. It happens—at a particular date, in a particular place, followed by definable historical consequences. We pass from a Balder or an Osiris, dying nobody knows when or where, to a historical person crucified (it is all in order) under Pontius Pilate. By becoming fact it does not cease to be myth: that is the miracle.”

“God is more than a god, not less; Christ is more than Balder, not less. We must not be ashamed of the mythical radiance resting on our theology. We must not be nervous about ‘parallels’ and ‘pagan Christs’: they ought to be there—it would be a stumbling block if they weren’t. We must not, in false spirituality, withhold our imaginative welcome. If God chooses to be mythopoeic—and is not the sky itself a myth—shall we refuse to be mythopathic? For this is the marriage of heaven and earth: perfect myth and perfect fact: claiming not only our love and our obedience, but also our wonder and delight, addressed to the savage, the child, and the poet in each one of us no less than to the moralist, the scholar, and the philosopher.”

- Quoted from God in the Dock by C.S. Lewis

What Myths Influenced Lewis’ Stories?

As a young lad growing up in Belfast, Northern Ireland, Lewis heard his Nurse Lizzie Endicott tell wonderful stories from Celtic mythology, which he often refers to in his books and letters. These fascinating Irish myths, as well as the landscape of County Down and the County Antrim coast of Ireland, filled with stories from Celtic mythology, would have a profound impact on the writing of Lewis’s beloved Narnia books.

The poignant myth of Tír na nÓg, the isle of eternal beauty and youth, where the Fae live, influenced The Magician’s Nephew and Lewis’ novel Perelandra. In The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, the valiant mouse Reepicheep seeks to sail to the world’s end to find Aslan’s country, just as St. Brendan does in the old Irish myth about him going on a voyage by the will of God to seek for the island of eternal youth and beauty. In The Magician’s Nephew, Digory and Polly travel with the flying horse Fledge on a quest given by Aslan to retrieve a magic apple that will play an important role in protecting Narnia against evil and saving the life of Digory’s mother. This scene is influenced by the myth of Tír na nÓg, probably one of the most ancient Irish myths (scholar Philip Freeman estimates it is at least 9,000 years old).

In the myth of Tír na nÓg, a man travels on a magic horse to Tír na nÓg, the isle of eternal beauty and youth. The hero returns later to find that time runs differently at home in Ireland than on the isle (time difference plays a role in all the Narnia stories). The same myth’s influence can be seen in Lewis’ novel Perelandra, where Ransom seeks to help The Green Lady Tindril be reunited with The King, Tor, to fulfill the quest that Maleldil (Christ) gave Ransom. As in the myth of Tír na nÓg, there is a warning not to set foot in a specific place, or there will be terrible consequences.

All of Lewis’s other Narnia books have a correlating theme of characters yearning and longing for the true Narnia, which is truthfully a longing for Aslan. Lewis wrote many times about a joyous longing he discovered through mythic stories (like the story of Tír na nÓg, like the Norse myth of Balder). He defined this joy as a universal human longing roused by the power of art, landscape, music, and myth.

Where Can We Learn More about Lewis’ Views on Myth?

Here are some incredible books about C. S. Lewis’s views on myth and the role myth played in his conversion from atheism to theism to Christianity.

1. Surprised by Myth by Grant Hudson and Justin Wiggins

2. God in the Dock by C.S.Lewis

3. The Weight of Glory by C.S.Lewis

4. The Monsters and The Critics by J.R.R.Tolkien

5. The Oxford Inklings by Colin Duriez

6. The Faun’s Bookshelf by Charlie W. Starr

7. The Most Reluctant Convert by David C. Downing

8. True Myth by Joseph W. Menzies

9. The Inklings and King Arthur edited by Sørina Higgins

10. The Myth Makers by Grand Hudson

If you liked this article on C.S. Lewis, you may enjoy the following:

The Enduring Legacy of C.S. Lewis

What You Should Know about C.S. Lewis' Brother Warnie Lewis

Why C.S. Lewis Remains Compelling

How C.S. Lewis Helps Us Understand This Cultural Moment

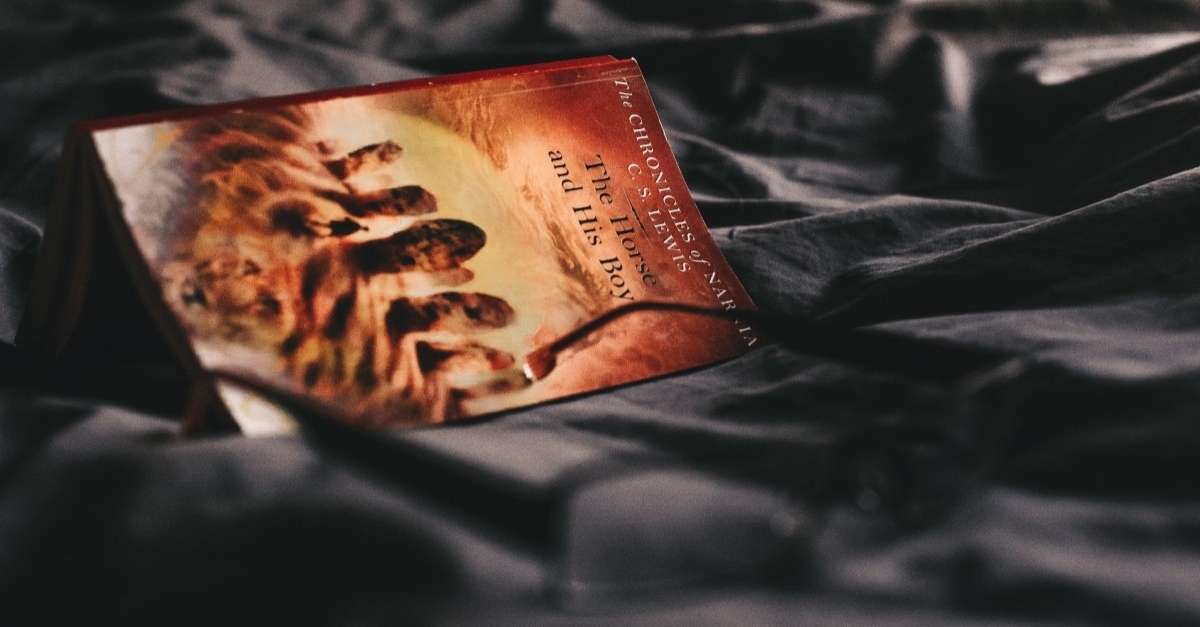

Photo Credit: K. Mitch Hodges/Unsplash

Justin Wiggins is an author who works and lives in the primitive, majestic, beautiful mountains of North Carolina. He graduated with his Bachelor's in English Literature, with a focus on C.S. Lewis studies, from Montreat College in May 2018. His first book was Surprised by Agape, published by Grant Hudson of Clarendon House Publications. His second book, Surprised By Myth, was co-written with Grant Hudson and published in 2021. Many of his recent books (Marty & Irene, Tír na nÓg, Celtic Twilight, Celtic Song, Ragnarok, Celtic Dawn) are published by Steve Cawte of Impspired.

Wiggins has also had poems and other short pieces published by Clarendon House Publications, Sehnsucht: The C.S. Lewis Journal, and Sweetycat Press. Justin has a great zeal for life, work, community, writing, literature, art, pubs, bookstores, coffee shops, and for England, Scotland, and Ireland.