While G.K. Chesterton’s official career was journalism (he wrote several thousand newspaper columns), he was a Renaissance man where words were concerned. He wrote poetry, Christians apologetics, detective stories, novels (everything from sci-fi to thrillers), political commentary, and gave BBC radio talks on various subjects. Chesterton published around 80 books in his lifetime, a considerable record for someone who only lived to age 62.

He wrote and talked about everything from history to architecture. However, Chesterton may be best remembered for his religious writings and fiction. He made compelling, always exciting arguments for Christianity that influenced many later thinkers, including C.S. Lewis and Malcolm Muggeridge.

10 Important Events in G.K. Chesterton’s Life

1. In 1875, Gilbert Keith Chesterton was born in London to a middle-class family of Unitarians.

2. In 1895, Chesterton got his first publishing job, working for George Redway.

3. In 1900, Chesterton published his first two books: the poetry collections Greybeards at Play and The Wild Knight and Other Poems.

4. In 1901, Chesterton married Frances Alice Blogg, who he credited with leading him back to Christianity via the Church of England.

5. In 1904, Chesterton published his first novel, The Napoleon of Notting Hill.

6. In 1908, Chesterton published two of his best-known books: Orthodoxy, a nonfiction defense of Christianity, and The Man Who Was Thursday, a metaphysical spy thriller.

7. In 1922, Chesterton entered the Roman Catholic Church. His friend and fellow Roman Catholic Hillaire Belloc observed that they both felt Roman Catholicism was Christianity’s best form and that England’s culture had declined after rejecting it. You can read more about his conversion below in Dan Graves’ article “Mr. Chesterton Makes His Confession.”

8. In 1925, Chesterton started his own newspaper, G.K.’s Weekly. The newspaper continued until Chesterton’s death without ever having many readers but providing an eclectic mix of journalism and opinions (including Chesterton’s own economic theory, Distributivism).

9. In 1930, Chesterton became the first president of the Detection Club, a London-based group that included the best-known writers of the Golden Age of Detective Fiction.

10. In 1936, Chesterton died in his Buckinghamshire home.

10 Important Quotes by G.K. Chesterton

1. “Books without morality in them are books that send one to sleep standing up.”—The Living Age, 1909

2. “It is an eternal truth that the fathers stone the prophets and the sons build their sepulchers, often out of the same stones.”—All I Survey

3. “I am a journalist and am so vastly ignorant of many things, but because I am a journalist, I write and talk about them all.”—The New York Times, 1921

4. “That is what makes life so splendid and so strange. We are in the wrong world. When I thought that was the right town, it bored me; when I knew it was wrong, I was happy. So the false optimism, the modern happiness, tires bus because it tells us we fit into this world. The true happiness is that we don’t fit. We come from somewhere else.”—Tremendeous Trifles

5. “And the upshot of this modern attitude is really this: that men invent new ideals because they dare not attempt old ideals. They look forward with enthusiasm, because they are afraid to look back.”—What’s Wrong With the World

6. “One can find no meanings in a jungle of skepticism; but the man will find more and more meanings who walks through a forest of doctrine and design. Here everything has a story tied to its tail, like the tools or pictures in my father’s house; for it is my father’s house.”—Orthodoxy

7. “Now the basis of Christianity as well as of Democracy is, that a man is sacred.”—1904 sermon, Preachers from the Pew

8. “Now compared to these wanderers the life of Jesus went as swift and straight as a thunderbolt. It was above all things dramatic; it did above all things consist in doing something that had to be done… This is where it was the fulfillment of the myths rather than of the philosophies; it is a journey with a goal and an object, like Jason going to find the Golden Fleece, or Hercules the golden apples of the Hesperides. The gold that he was seeking was death. The primary thing that he was going to do was to die…”—Everlasting Man

9. “The function of imagination is not to make things settled so much as to make settled things strange; not to make wonders facts, but facts wonders.”—The Bookman, 1903

10. “A man who has faith must be prepared not only to be a martyr, but to be a fool.”—Heretics

Further Reading: 20 Wise Quotes from G.K. Chesterton

10 Things You Probably Didn’t Know about G.K. Chesterton

1. He wrote detective fiction. In 1910, Chesterton published the first of many mystery stories about Father Brown, a Roman Catholic priest who solves crimes in his spare time. In 1928, he became a founding member of the Detection Club, alongside such writers as Dorothy L. Sayers, Ronald Knox, and Agatha Christie. Chesterton was the group’s first president.

2. He started in art. Although Chesterton became best known for his writing, he studied at the Slade School of Art with plans for a career in illustration. He never completed his degree, although he drew caricatures throughout his life.

3. His name is in space. In 2012, a crater on the surface of Mercury was named Chesterton.

4. He wrote biographies. While Chesterton’s fiction and apologetics are probably his most famous books today, he wrote several biographies of famous figures, especially early in his career. His biographies of Thomas Aquinas and Francis of Asissi are still widely available.

5. He influenced the Inklings and their friends. While Chesterton wasn’t part of the 1930s-1940s Oxford writers’ group organized by C.S. Lewis, he was connected to the group in interesting ways. Through the Detection Club, he knew Dorothy L. Sayers, who was friends with at least two Inklings. In 1935, Chesterton sent a letter to future Inkling Charles Williams praising his poetry. Later, Williams contributed book reviews to G.K.’s Weekly. Lewis called Chesterton’s book Everlasting Man crucial to his conversion.

6. He could laugh at himself. While Chesterton had a formidable intellect, he wasn’t afraid to poke fun at his own shortcomings. One story describes how a woman who met Chesterton in London during World War I asked why he wasn’t “out at the front.” Chesterton, who weighed over 280 pounds, answered, “If you go round to the side, you will see that I am.”

7. He wasn’t afraid to be unpopular. Many of Chesterton’s writings critique fashions of the day. For example, he critiqued modernists for being overly concerned about being current, as if they had to throw out anything that predated them. One of his most famous books, Heretics, critiques well-known figures like Rudyard Kipling, Charles Darwin, and H.G. Wells.

8. He befriended people he disagreed with. While Chesterton embraced unpopular positions and openly critiqued many people he disagreed with, he wasn’t unpleasant to them. He criticized several non-Christians in print, debated them publicly, and treated them as friends. He disagreed with George Bernard Shaw but said Shaw was “something of a pagan, and like many other pagans, he is a very fine man.” Shaw also considered Chesterton a friend, congratulating him in 1915 when he recovered from a severe illness: “you have carried out a theory of mine that every man of genius has a critical illness at 40…”

9. He embraced paradox. While Chesterton made logical arguments for Christianity’s rationality, he didn’t believe he had to omit paradoxes from his beliefs. Many of his writings in Orthodoxy are devoted to the idea that Christianity is essentially a paradox, but a poetic one that explains life better than any alternate explanation.

10. He wasn’t an anti-Semite. Chesterton died before Israel was established as a political nation and made the unpopular argument that Jews should be treated as a distinct people group and have their own nation. Some of his wording (“The Jewish problem”) and jokes about Jews have become dated; for that reason, many have accused him of being anti-Semitic. In 2012, the American Chesterton Society rebutted these claims with an entire issue of its magazine devoted to Chesterton’s views on Jews.

5 Great Books about G.K. Chesterton

Given how prolific Chesterton was, knowing where you should start with his work can be challenging. The following are some great books to start learning about Chesterton’s life:

A Year with G.K. Chesterton, edited by Kevin Belmonte

G.K. Chesterton: The Apostle of Common Sense by Dale Ahlquist

The Autobiography of G. K. Chesterton

Wisdom and Innocence: A Life of G.K. Chesterton by Joseph Pierce

Gilbert Keith Chesterton by Maisie Ward

You can also check out the American Chesterton Society’s reading plan for beginners.

Mr. Chesterton Makes His Confession

By Dan Graves, MSL

“How in blazes do you know all these horrors?” cried Flambeau [a criminal in one of Chesterton’s fictions].

The shadow of a smile crossed the round simple face of his clerical opponent. “Oh, by being a celibate simpleton, I suppose,” he said. “Has it never struck you that a man who does next to nothing but hear men’s real sins is not likely to be wholly unaware of human evil?”

Chesterton wielded one of the great pens of his day. His Father Brown detective stories are as delightful to nibble as cinnamon apples. Renowned in literature, Chesterton was also a passionate and humorous apologist for the Christian church. Especially the Catholic church. As a young man he showed considerable literary talent and began to edit a little paper. In time this became his life’s work. He did a lot of criticism. He had an uncanny knack of seeing what was crucial in any author’s work and the clarity to smell the real worth or the real flaw of any argument.

Paradox was his forte. Paradox, said Chesterton, “is truth standing on her head to attract attention.” As used by Chesterton paradox is either a statement that at first glance seems false but actually is true, or a “commonsense” view exposed as false. He used it so frequently it could become tiresome in his longer works. But in short essays it is scintillating and refreshing. Here is an example on the topic of history from The Everlasting Man, his paean to Christ which shows that the spiritual is more real than those things we consider tangible reality. “So long as we neglect [the] subjective side of history, which may more simply be called the inside of history, there will always be a certain limitation on that science which can be better transcended by art. So long as the historian cannot do that, fiction will be truer than fact.”

Chesterton could be absent-minded. Once he dropped a garter. While down on the floor groping for it, he found a book and began to read it, the garter completely forgotten. He would stand in the middle of traffic, lost to his surroundings, deep in thought. Still, he had tremendous concentration for writing and was ever fixed on the eternal truths that make the wisdom of this world foolish. Thus he could say succinctly of the agnostic George Bernard Shaw, “He started from points of view which no one else was clever enough to discover and he is at last discovering points of view which no one else was ever stupid enough to forget.” His witticisms were repeated everywhere.

On this day, Sunday, July 30th, 1922, Chesterton took a walk with Father O’Connor. His 400 pounds were to be baptized into the church that he had defended all his life. Looking for his prayer book he accidentally pulled out a three penny thriller instead. At last he found the text and made his first confession. Asked why he joined the Catholic church Chesterton replied, “To get rid of my sins.”

Bibliography

1. "Chesterton, Gilbert Keith." Dictionary of National Biography. Edited by Leslie Stephen and Sidney Lee. London: Oxford University Press, 1921 - 1996.

2. D'Souza, Dinesh. The Catholic Classics. Huntington, Indiana: Our Sunday Visitor, 1986.

3. Ffinch, Michael. G.K. Chesterton. New York: Harper and Row, 1986.

4. O'Brien, John A. Giants of the Faith. Image, 1960.

5. Pearson, Hesketh. Lives of the Wits. New York: Harper and Row, 1962.

6. Slosson, Edwin E. Six Major Prophets. Boston, 1917.

("Mr. Chesterton Makes His Confession" by Dan Graves was first published on Christianity.com on April 28, 2010.)

Further Reading:

The following Christianity.com articles cover people who influenced or were influenced by Chesterton:

Why Was Charles Williams the Odd Inkling?

What You Need to Know about Dorothy L. Sayers

10 Things to Know about Ronald Knox

10 Things You Need to Know about George MacDonald

10 Things You Need to Know about the Inklings

10 Things You Need to Know about J.R.R. Tolkien

The Enduring Legacy of C.S. Lewis

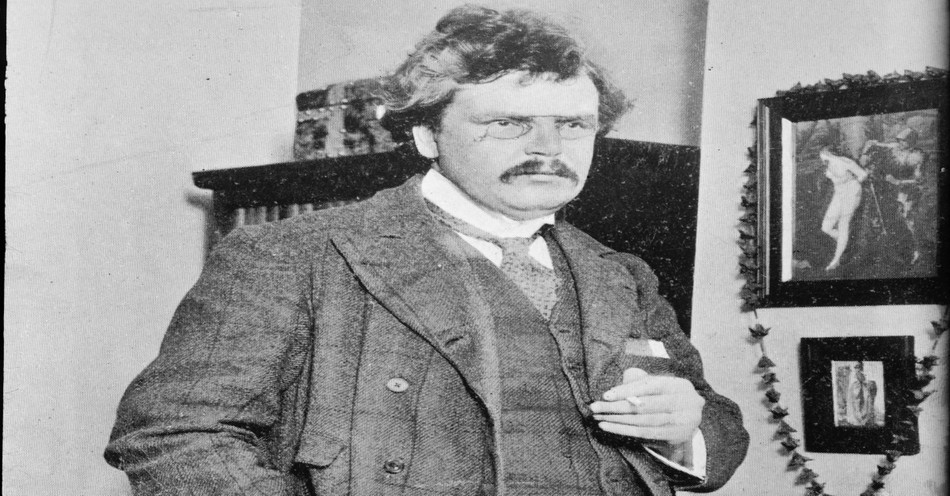

Photo Credit: 1915 photo, George Grantham Bain Collection, Library of Congress. Made available via Wikimedia Commons.

This article is part of our People of Christianity catalog that features the stories, meaning, and significance of well-known people from the Bible and history. Here are some of the most popular articles for knowing important figures in Christianity:

How Did the Apostle Paul Die?

Who are the Nicolaitans in Revelation?

Who Was Deborah in the Bible?

Who Was Moses in the Bible?

King Solomon's Story in the Bible

Who Was Lot's Wife in the Bible?

Who Was Jezebel in the Bible?

Who Was the Prodigal Son?