Scripture contains a plethora of terms and titles to describe who Jesus is and what he accomplishes. Some titles are taken up by Jesus himself, others are employed by the crowds, the disciples, or the authors of Scripture. One of the frequent titles given to Jesus is that of “King.” Yet, what do we mean when we use this title? After all, Jesus certainly does not reside in a palace or wear a bejeweled crown.

For many, the language of kingship seems aggressively triumphalist. It speaks of a reign based on strength, dominance, and the wielding of oppressive power. Kingship is equated with colonialism, moving throughout the world to exploit nations and peoples.

Let’s be honest, historically, this is pretty much what happened. Throughout the ages, kings have shown themselves to be coercive and power-hungry.

For this reason, many Christians reject king-language when referring to Jesus. We would never wish to suggest that Jesus is tyrannical and oppressive. Yet we cannot deny the fact that Scripture frequently refers to Jesus as a king.

Even the inscription above his cross read “Jesus, King of the Jews” (Matthew 27:37). The question that remains, therefore, is not whether “king” is an appropriate title for Jesus, but rather how this title might be applied.

Recognizing the kingship of Jesus helps us have a true and faithful understanding of who Jesus is. In fact, it is for this reason that the Church dedicates the last Sunday of the liturgical year to this theme. Jesus is King; this is a biblical fact. The kingship of Jesus is revealed in three fundamental ways.

1. Jesus Is the Counter-Cultural King

Scripture continually contrasts the kingship of Jesus with the kings of the world. Jesus is a king like no other. While we may have negative associations with kingship today, it is good to remember that the ancient world had a similar understanding. Kings ruled through military power, often taking over neighboring nations and peoples.

Furthermore, the early followers of Jesus lived in the shadow of Rome, an empire rooted in slavery, violence, and oppression. Depictions of Jesus as “the ruler of kings” (Revelation 1:5), or “the King of kings, and Lord of Lord’s” (Revelation 19:16), therefore, would have sounded completely out of place.

Visions of tyrannical kings and exploitative rulers play in the background of these biblical titles. In fact, the language of someone being “King of kings, Lord of lords,” initially described an emperor, one holding dominion and power over other kings and nations.

In the days following Christ’s death and resurrection, this title would have popularly referred to the Roman emperor. The language conveyed earthly strength, domination, and violence.

What makes the language of kingship so important when applied to Jesus is that this language works against the grain. Jesus is a different type of ruler than the Roman emperor. The kingship of Jesus is counter-cultural, it speaks of an alternate reality.

The way Jesus expresses his power and lordship is not in the wielding of might and dominance, nor is it in exploiting others. In fact, when the devil tempts Jesus to grasp earthly power for himself (Matthew 4:9), Jesus remains faithful.

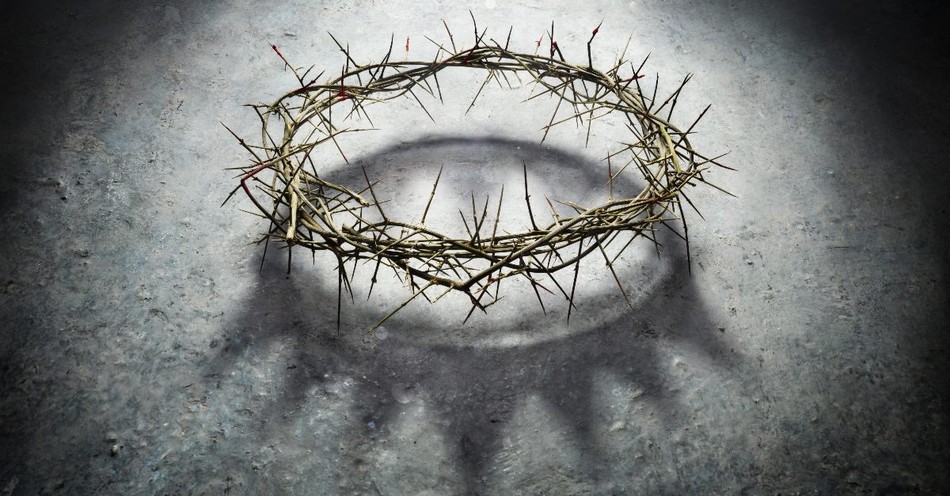

Scripture takes the language of kingship and turns it on its head. Jesus is the true King because he is different than all the false kings of the world. Jesus rules from the cross, not a throne; his crown is one of thorns, not jewels.

Thus, when we refer to Jesus as King, we describe something distinctly contrary to the normative understandings of kingship and worldly power. By doing so, we expose the emptiness of earthly kingship and power.

2. Jesus Rules in Love

If Jesus is a countercultural king, how is his reign different than that of earthly kings and monarchs? In the Book of Revelation, after referring to Jesus as the “ruler of kings,” John describes him as “the one who loves us” (1:6). The reign of Jesus is a reign of love. This, undoubtedly, is countercultural to the way we normally think of those with royal power.

Do kings and monarchs love their subjects? Do emperors feel passion for the ones they rule over? Again, we must recognize that this description of Jesus as the loving king occurs with the violent power of Rome ringing in the background. No one would think that Rome was an empire of love.

Jesus doesn’t wield power — he pours out his love. Whereas other kings may rule in strength, Jesus rules out of weakness. While other kings rule out of hate, Jesus exudes love. Importantly, John declares that the love of Jesus is a present reality.

The love of Jesus is not past tense; it is not something we simply read about when we open the pages of the Bible. The divine love of Jesus makes its way into our present lives. Jesus is king precisely because his love covers us even today.

3. Jesus Rules in Sacrifice

Jesus is a different king, not simply because he loves us, but because he empties himself for our redemption. The Book of Revelation describes the kingship of Jesus this way: “To him who loves us, and freed us from our sins by his blood” (1:5). Jesus willfully enters the lowest of places.

In fact, in emptying himself, Jesus takes the violence of earthly kings on himself. Jesus is king not because he wields earthly power, but because he suffers under it. In doing so, Jesus provides liberation from all that keeps us spiritually enslaved.

The contrast between Jesus and earthly kingship is beautifully depicted in the conversation between Jesus and Pilate (John 18:33-37). Pilate, who represents worldly power, simply cannot understand Jesus or his ministry.

He makes several attempts to get Jesus to admit his own kingship. In response, Jesus says, “My kingdom is not of this world, if it were, my servants would fight.” Fighting is what human kings do. Earthly kings use their subjects to fight for the king’s protection and livelihood. This is the kingship that Pilate understands.

Jesus is a different king because he doesn’t come to fight or protect his life. Jesus comes to sacrifice himself for the sake of others. Jesus did come to be served but to serve, and to give his life as a ransom for others (Mark 10:45).

This gift of himself sets us free from everything that oppresses us or spiritually dominates us. By giving himself, by pouring out his own blood, Jesus sets us free.

What Does This Mean?

Recognizing that Jesus is our king calls us to recognize that our lives are to follow his example. As Jesus is the King who stands in opposition to the false kings of earthly power, Christians are called to be equally countercultural. We are to be a different people, a set-apart people.

As followers of the heavenly king, the kingdom to which we belong, which we participate in and bear witness to, is a kingdom that defies coercive power and domination. This truth must be as much a part of our lives as it was a part of his.

Because Jesus is the King who rules in love, our expression of his kingdom is also to be rooted in that love. We are called to bear witness to the radical proclamation that the love of the King makes its way to all.

Similarly, as the kingship of Jesus is one of selfless sacrifice, we are to bear witness to this through manifestations of forgiveness, grace, and service.

Ultimately, heralding Jesus as our king is not simply about understanding who Jesus is, it is also about recognizing who we are, and to what we are called to in this world.

For further reading:

Why Did Kings Believe That They Were Ordained by God?

What Does it Mean That Jesus Is Prophet, Priest, and King?

What Does it Mean That God Is the King of Glory?

What Does it Mean That Jesus Is the King of the Jews?

Photo Credit: ©iStock/Getty Images Plus/RomoloTavani