At its peak in the 1950s, Freemason lodges in America had 4.1 million members—almost eight percent of the American male population. Freemasonry has been called everything from a harmless men’s social club to a cover for Satanist groups. Movies like National Treasure or From Hell have imagined the Freemasons doing anything from hiding the Knights Templar’s secret treasure to covering up Jack the Ripper’s killings (on Queen Victoria’s orders, no less).

What do we know for certain about the Freemasons? Is there something creepy about a group that isn’t a church or recovery program, uses vaguely religious rituals, and reaches millions of people around the world? What is the appeal?

What Are the Freemasons?

Many Freemason groups exist worldwide, with no formal international structure regulating all of them. Most will say their rituals are informed by founding documents known as The Old Charges, which describe rituals that reportedly date back to biblical times.

Granting that it’s impossible to describe every Freemason lodge, we can give a general definition: the Freemasons are groups that meet at Masonic lodges and have detailed rituals for joining the lodge and ascending through different offices. Members are almost always male (there is a sister organization called The Order of the Eastern Star). Members must follow various rules and pass (allegedly) secret rituals.

The group is called “Freemasons” because its rituals contain images and language inspired by the medieval stonemason guilds that apprenticed workers to cut stones. Andrew Prescott reports that “freemason” began as a term for stonemasons who worked on freestone (limestone or sandstone that workers cut with fine-toothed saws). “Lodges” were originally the name of a stonemason’s building site but developed to mean places where stonemasons met to discuss business.

Stonemasons also contributed something else to later Masonic lore. Historian John Dickie explains in The Craft that medieval guilds had carefully designed structures. Members advanced from apprentices to skilled workers if they met their teacher’s standards. As Dickie goes on to explain in an interview for the History Extra Podcast, Freemason rituals used the stonemasons’ emphasis on advancing through ranks and images from stonemasons’ tools as metaphors for men’s spiritual development.

What Do Freemasons Believe?

Of course, saying that Freemason rituals are symbolic ways to describe how men grow raises an important question: What should members be growing into?

Britannica explains members must believe in a Supreme Being, practice charity, and obey the law. So, they’re growing into law-abiding, charitable theists.

Generally, Masonic lodges have reported that their beliefs are compatible with all faiths. For example, in 2007, the United Grand Lodge of England released the following statement:

“Freemasonry is not a religion, nor is it a substitute for religion. It demands of its members belief in a Supreme Being, but provides no system of faith of its own. Its rituals include prayers, but these relate only to the matter instantly in hand and do not amount to the practice of religion. Freemasonry is open to men of any faith, but religion may not be discussed at its meetings . . .”

The statement goes on to say that members do have to follow the Sacred Volume of the Law and their membership oaths. The Sacred Volume of the Law appears to vary from one grand lodge to another—it may or may not be based on the Bible.

The statement suggests that Freemasonry’s teachings about God are similar to twelve-step programs where every member believes in a higher power. We see that interfaith emphasis in Albert Pike’s 1871 book Morals and Dogma of the Accepted Scottish Rite of Freemasonry:

“Masonry, around whose altars the Christian, the Hebrew, the Moslem, the Brahim, the followers of Confucius and Zoroaster, can assemble as brethren and unite in prayer to the one God who is above all the Baalim, must needs leave it to each of its initiates to look for the foundation of his faith and hope to the written scriptures his own religion. For itself it finds those truths definite enough, which are written by the finger of God upon the heart of man and on the pages of the book of nature.”

Baalim is an archaic biblical Hebrew term for Canaanite gods (especially Baal), sometimes also used for demons; Brahim is an archaic spelling for the Hindu caste of Brahmins. Therefore, Pike appears to be saying that Freemasons, whatever their religion or philosophy, share a belief that:

- God exists (even Confucianism emphasizes a higher power in semi-religious terms).

- God is generally understood in monotheistic terms (Hinduism reports that there is one God, Brahman, that all other gods and spirits emanate from).

- God is bigger than ancient pagan definitions (where gods are usually territorial deities, maybe demons).

- Nature and humanity’s inner knowledge of God both point to his existence.

Various Freemasons have argued whether Pike accurately portrays what every Masonic lodge teaches. However, Pike’s work does show that lodges promote an interfaith perspective. Some have raised concerns about whether this emphasis implies that all monotheists worship the same God. Various Christian groups have argued that this means Freemasonry doesn’t fit the historic Christian faith. The Roman Catholic Church has consistently said for centuries that Catholics cannot be Freemasons. The Greek Orthodox Church made a similar statement in 1933. On the other hand, Protestants in Britain and Ireland generally do not see any issue with Freemasonry. Some would argue that if Augustine is correct in Plundering the Egyptians that Christians can affirm elements in pagan cultures that fit Christan ideas, then Christians are free to affirm Masonic ideas fitting Christian teachings.

What Are Freemason Rituals?

While most of us can get behind the Freemasons’ emphasis on charity, theism, and being law-abiding citizens, we may find the rituals weird. Therefore, we should ask: What kind of rituals do they follow?

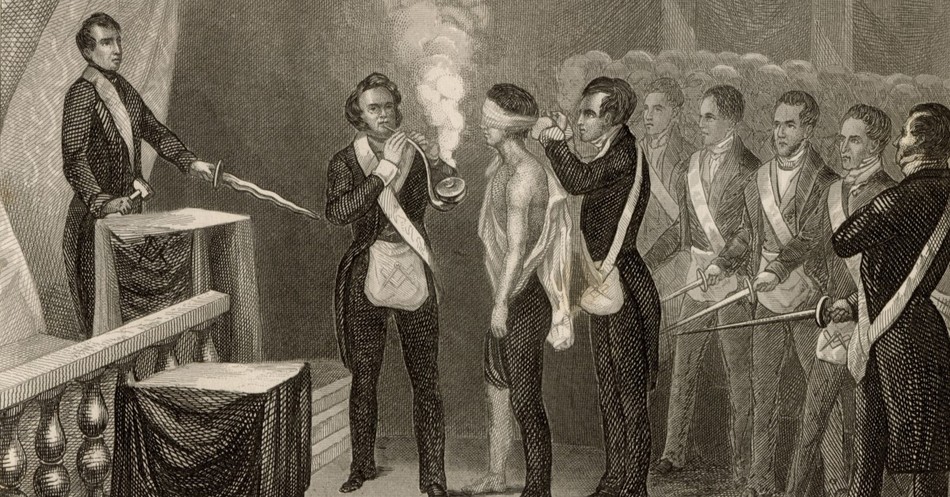

Masonic rituals vary, but they usually involve some processions and movements that symbolically act out spiritual priorities (for example, walking blindfolded into a room may represent taking a leap of faith). Symbolic props and allegorical stories about Solomon’s temple (especially about legendary architect Hiram Abiff) are often involved. The rituals take members through many ranks or degrees, depending on the lodge. Usually, there are three basic grades that the various ranks fit within:

- entered apprentice

- fellow of the craft

- master mason

The rituals combine images from many sources.

First, stonemason guilds provided images and a mythic vision of ancient roots. Dickie notes in The Craft that medieval stonemason guilds developed stories about their craft going back to the construction of Solomon’s Temple. Andrew Prescott notes these stories probably became the basis for the Old Charges.

Second, many alternative religious ideas popular in the Renaissance and Reformation periods influenced it. Many rituals owe something to Hermeticism, a worldview inspired by the ancient Greek religion Hermetism. As Earl Fontainelle explains, Masonic rituals also borrow from legends about Solomon’s temple, which informed many other secret societies from ancient times onward.

Third, legends about other historical groups worked their way into Freemason mythology. Pierre Mollier explains how many lodge rituals adopted legends about the Knights Templar allegedly surviving medieval persecution and becoming the Freemasons.

All the many influences created a complex layer of rituals that Freemasons believe provide a visual path to explain how men spiritually grow, a path outlined centuries earlier.

But how old is it really?

When Did the Freemasons Start?

As Jeremy Pemberton notes, most Freemason groups say their rituals are from “time immemorial,” ancient beliefs secretly passed down for centuries. That is a fairly common claim among secret societies and does not always hold up to scrutiny.

Historians see Freemasonry as gradually developing from practical stonemasons to modern groups using masonic imagery, the key shift in the Reformation period. David Stevenson explains how William Schaw reorganized and reinvigorated Scottish stonemason guilds after King James IV of Scotland appointed him master of works in 1584.

Lodges in Scotland and England became more connected, with a key moment arriving on June 24, 1717. Members from four masonic lodges met at the Goose and Gridiron Tavern at St Paul’s Churchyard in London, combining to make the first grand lodge connecting smaller lodges. Then, in 1723, The Constitutions of the Free-Masons was published, setting down the masonic lodges’ alleged history—how they were connected to the medieval mason guides, how their ideals went back even further to Solomon’s stonemasons. From there, Masonic lodges developed to include many kinds of businessmen as members.

What Made Freemasons So Popular?

Now that we know where Freemasonry comes from and what it believes, we may still wonder why it’s so popular. What is the appeal?

Certainly, the emphasis on secret rituals made it exciting, a form of the ever-popular secret boy’s club. It also offered what many secret societies offered: leadership and a kind of education for people who didn’t have access to other opportunities. As discussed in the next section, the yearning for ritual is something all humans have in some form.

More practically, Masonic lodges emphasized professional networking and good behavior. Members who broke etiquette rules could be kicked out of lodges. So, lodges provided a trusted way for businessmen to make new contacts.

Historically, Freemasons also offered protection. Dickie highlights how Freemason lodges became a key resource for Jewish men, who couldn’t join many professional associations. Jessica Harland-Jacobs explained in an NPR interview that Freemasons’ emphasis on helping members made a big difference in a pre-insurance laws era.

Freemasons’ emphasis on networking and rituals influenced various other groups. Dickie gives two curious examples in the History Extra podcast: the mafia and Mormonism.

- The mafia stemmed from Cosa Nostra, a nineteenth-century Sicilian group that emulated the Freemasons’ structure to provide landowners with a mercenary protection network when corrupt police wouldn’t protect property. After it evolved into a criminal organization, the mafia’s networking and mutual protection culture became a way for criminals to protect each other.

- Church of Latter-Day Saints founder Joseph Smith and several other early Mormons were Freemasons and adopted Masonic ideas into the church. Michael W. Homer explains in Joseph’s Temples that the masonic influence helps to explain Mormonism’s exclusive membership rituals and some of its messy history. For example, Freemasons have historically not welcomed African-American members, and the Church of Latter-Day Saints did not ordain African-American priests until 1978.

Mormonism is not America’s only social sphere that embraced Freemasonry. Since American colonies were mostly settled by Protestants, the Catholic church never had the same political control it had in Europe, so American Freemasons experienced less persecution. As Peter Feuherd explains, Freemasonry also became an ideal meeting place during the Enlightenment for Americans to discuss civil religion, freedom, and reason in ways that challenged European models. Since Freemasonry became a mark of social status and a space to discuss revolutionary ideas about God and Power, it’s unsurprising that many Founding Fathers were involved in Masonic lodges.

Why Do Freemasons Have Rituals?

Christians have often worried about Freemasonry’s emphasis on secret rituals. In some cases, particularly during the Satanic Panic of the 1980s-1990s, evangelical Christians have worried about the possibility of satanic activities hiding behind the rituals.

While there have been various accounts of strange activities happening at masonic meetings, historians point out how often these accounts are shown to be written by con artists or just poorly researched.

While we may find secrecy creepy, the fact that many Freemason rituals have been published and that various lodges have allowed scholars to research their work means that there are far fewer secrets than we think. Furthermore, “secret rituals” by themselves don’t prove much. If secrecy always implied Satan worship, we would need to investigate every 12-year-old’s secret clubhouse. Sometimes, secrecy is a game more than anything else.

We must also consider that the Freemasons weren’t that unusual when they started. Most medieval guilds told legends about their origins. Many people in the Reformation era (for example, Rosicrucians) explored rituals with magic-sounding images.

In many ways, our craving for rituals hasn’t changed. Secular and Christian groups continue to create rituals to commemorate special life changes. During the 1990s, books like Robert Bly’s Iron John generated the mythopoetic men’s movement rituals. Various Christian men’s books (such as Robert Lewis’s Raising a Modern-Day Knight) have discussed ways to apply medieval knighthood rituals to men’s development.

We all have ritual behaviors, even if we don’t follow mythopoeic and biblical manhood (or womanhood) discussions. As Dickie points out in The Craft, “When we laugh at the rituals of others, we forget how much of our own lives is invisibly ritualized.” We all build our lives around regular habits that are shorthand ways to communicate things—things as simple as clapping our hands to show appreciation. As James K.A. Smith observes in You Are What You Love, we also have regular habits (where we buy food and spend our spare time) that are essentially rituals showing what we value and reinforcing those values.

In church, many official and unofficial rites of passage symbolically show we are growing and changing. We hold baptisms to show our new faith. We hold dedications or christenings to communicate our value for raising children in our faith. We partake in Communion because the Eucharist changes us and because we must remember our spiritual priorities (Christ’s sacrifice on the cross). We participate in weddings, funerals, and holiday celebrations to highlight important life events. We host church camp songs and develop insider slang for our church’s special culture.

Can Christians Be Freemasons?

Granting that humans seem hardwired to create rituals, we do have questions we need to ask as Christians before joining a Freemason lodge.

First, we should consider whether Freemasonry’s attitude toward the Supreme Being fits the Christian view of God. As mentioned earlier, there has often been an Enlightenment tone to Freemason lodges’ discussions about God, which may present problems. Enlightenment thinkers often embraced deism—God as a distant figure, the great clockmaker who winds up the universe and lets it play out.

The Freemasons’ broad view of the Supreme Being may also create problems. We can agree with Pike’s idea that God provides evidence of himself in nature (Romans 1:20). We can agree that there is an inherent human desire for God that suggests God must exist: a God-shaped hole in our hearts. However, neither of these statements leads to the conclusion that Muslims, Hindus, and Christians worship the same god. We need to determine whether following Masonic ideas about God is like joining a 12-step program or joining a universalist church.

Third, granting that we seem hardwired to create rituals or liturgies for our lives, we should ask what the rituals contain. Do they have specific images from pagan cultures that should worry us? Images from Hermeticism have a Gnostic tone that doesn’t fit well with Christianity.

Fourth, we must consider a local lodge’s activities. What do its donations support? Do their leaders have dubious reputations? Since Masonic lodges vary so much, there may be genuinely sinister things behind some of them. For example, in the 1980s, Italian authorities discovered that a disgraced lodge, Propaganda Due, was laundering money for the mafia and connected to several assassination attempts.

Hopefully, the Freemasons we know aren’t in anything more sinister than a men’s social club that promotes charity causes. If a local lodge proves to be involved in something darker, we already know what to do: pray for them, as we are called to pray for anyone stuck in spiritual darkness. We are also called to love them well, remembering that we are all spiritually broken.

Photo Credit:©GettyImages/Tom Chalky - Digital Vintage Library

Christianity.com's editorial staff is a team of writers with a background in the Christian faith and writing experience. We work to create relevant, inspiring content for our audience and update timely articles as necessary.

.jpg)