Most evangelical churches don’t have icons. They may have an empty crucifix at the front or modern portraits of Jesus in a pastor’s office. This is typical for many Protestant churches that don’t have a high church background, which is understandable.

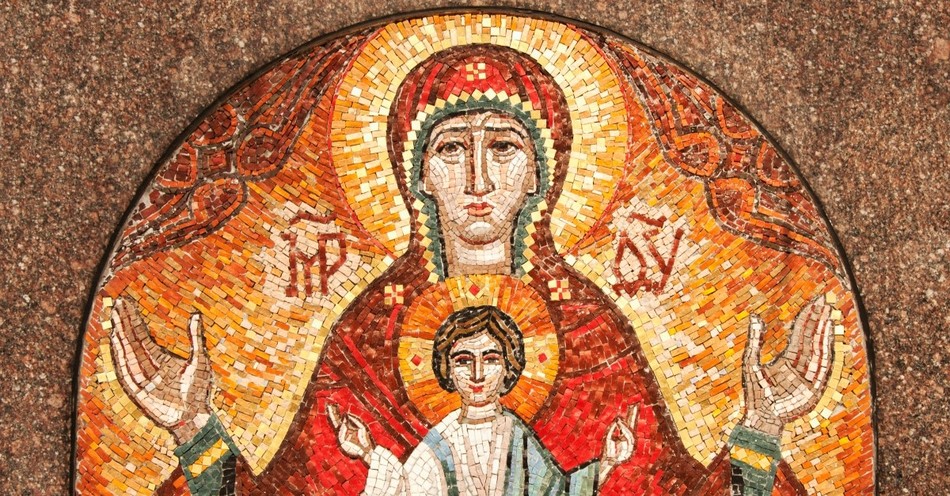

We would see major differences if we walked into an Eastern Orthodox Church or a Roman (or Byzantine) Catholic Church. One of these differences is the portrait styles of Christ, Mary and the Apostles, the saints, and even figures from the Old Testament. The style is known as Iconography, which dates back to the early church and is still used. It continues today in high church denominations, including some Protestant ones such as Lutheran churches and Anglicans.

We may find icons confusing or even concerning if we’re unfamiliar with them. As a former evangelical who became an Anglican Catholic, I understand. I was confused and concerned for a while, and it took me a few years to overcome that fear and embrace it.

Even if someone does not embrace Christian iconography, they can at least respect it. However, doing that means having an accurate, authentic understanding of what icons are and where they come from.

What Is Iconography?

As previously mentioned, iconography or holy icons depict Christ and church figures in a very precise and traditional way. One may see it as an ancient art, but it is much more than that for the high churches of Christianity. As Fr. Geoff Harvey of Good Shepherd Orthodox Church puts it,

“Icons have been described as ‘Theology written in images and color.’ Icons are not just pictures — they are sacred images, which convey spiritual truth in picture form, and are sometimes described as windows to heaven.”

The purpose of iconography is not just having it in one’s house, like a photograph of one’s family. Icons aid in worship and prayer. They may appear in the sanctuary of high churches or prayer corners in individual homes. Whatever their location, they help people focus on Christ as they reflect on Christ and the saints.

A common misconception about iconography is that people worship them. For example, during the eighth century, Muslims and pagans accused Christians in the Byzantine Empire of idol worship because of their crucifixes and iconography. Not only is this false but it has been debunked repeatedly since the early church (we’ll get to that in a bit). This false claim not only inaccurately defines our high church brothers and sisters, but it leads to bearing false witness against them—which the 10 commandments warn us not to do.

We will return to how icons are used in worship and prayer momentarily. First, we need to understand the history of iconography.

When Did Christians Begin Using Iconography?

Before Emperor Constantine the Great legalized Christianity in 313 A.D., Christians were persecuted and underground—metaphorically and physically. They often worshipped in catacombs, a burial ground place that pagans used.

While Christians did not agree with some of these pagan customs, they redeemed the location by making it a sight of worship by adding Christian paintings and mosaics. Scholars now consider the Christian art found in the catacombs to be the origin of iconography.

The images were simple and sometimes subtle to prevent Roman suspicion. For example, they often used symbols (such as anchors or the Chi-Rho) to represent Christ or biblical concepts. After the legalization of Christianity, iconography found its place in church buildings.

Why Was Iconography Important to the Church?

Icons also served an important practical purpose in church history: most people were illiterate, so images conveyed Christian ideas to people who couldn’t use books. Even when people could read, few Bibles were available. As Fr. Chris Margaritis states in an interview about Orthodox Easter, “for three-quarters of the church life until the 1500s, we didn’t have Bibles.”

Before Johannes Gutenberg invented the printing press, Bibles had to be translated by hand, making them scarce in available copies. As Margaritis observes later in the interview, the Eastern Orthodox Church still had difficulty accessing printed Bibles since the Muslim-controlled Ottoman Empire ruled southeastern Europe from the 1400s to the 1800s.

Since icons often taught biblical content when nothing else was available, Orthodox churches developed a particular structure: the icons tell the story of the Bible and church history. The left side typically shows icons of the Old Testament figures, the center shows Gospel stories, and the right side shows the early church and later saints. The ceiling usually shows a large icon of Christ surrounded by the apostles and prophets—connecting everything, and the congregation, to Christ and his clouds of witnesses as Hebrews 12:1-2 instructs.

From teaching to prayer and worship, iconography played a crucial role for the early Christians and continues to aid millions worldwide today.

However, this does not mean icons have not been controversial sometimes. Christians have argued about their usage time and time again—and some, like John Calvin and the Puritans, have stamped out their usage. So, why have Christians argued about icons? How have high church Christians typically responded to the debates?

Why Have Christians Debated Iconography?

Concerns about whether icons had become something Christians worshipped instead of using them to worship God led to two sides: iconoclasts who forbade icons and iconophiles who supported their use.

Byzantine Emperor Leo III forbade iconography usage in 730 A.D., which became known as the iconoclast controversy. While some agreed, many in Western Europe under the Bishop of Rome disagreed. One critic was John of Damascus, who wrote the “Discourse on Sacred Images,” a profound defense of iconography.

This growing divide in Christendom eventually led to the second Council of Nicaea, which occurred in 787 A.D. Empress Irene of Athens hosted the council, with over 367 Bishops discussing the iconoclast issue. John of Damascus’ writings and reputation served him well at this meeting, as he famously stated,

“Of old God the incorporeal and uncircumscribed was not depicted at all. But now that God has appeared in the flesh and lived among humans, I make an image of the God who can be seen. I do not worship matter but I worship the Creator of matter, who for my sake became material and deigned, to dwell in matter, who through matter effected my salvation. I will not cease from worshipping the matter through which my salvation has been effected.”

In other words, he claimed that Christians do not worship icons but the one who is depicted, i.e., Christ and Christ alone. The council decided to reinstate icons for prayer and worship.

Iconoclasm eventually returned during the latter years of the Reformation. While Martin Luther approved icons, other reformers (such as Ulrich Zwingli, John Calvin, and eventually the Puritans) thought otherwise. They often removed (sometimes destroyed) icons, including crosses, as they saw any image as a distraction or an idol.

How Can Christians Gracefully Discuss Iconography?

Iconography remains a heated debate between Christians, especially on the internet. Both sides have their points. We can understand the Protestant caution not to fall into idolatry. We can also understand the high church emphasis on respecting the church’s history and tradition or artwork that honors God. So, how can we civilly discuss the problem and respect differences?

First, we can do our research. If we disagree with one side, we can go to direct sources to see their arguments rather than biased sources that fit our view. We can make a point to see expert sources—what historians and clergy advise.

Second, we can practice viewing each other as brothers and sisters in Christ. We are called to build relationships and love our neighbors well. Being hostile from the start divides and provides ammunition to unbelievers who already believe Christians don’t love each other well.

Third, be open to the possibility of change. We often assume we have all our theological opinions figured out and airtight, only to find that generations of Christians have held other perspectives. Even if your mind is not completely changed, your heart towards others can be.

Take it from me. I was an Evangelical Christian for over 20 years who constantly criticized Christians who used icons. In 2022, I humbly switched sides after studying high church Christianity and became an Anglican Catholic who openly uses and loves iconography.

In a digital age with countless resources, let us use knowledge to understand and respect others. You may even learn something new.

Photo Credit:©GettyImages/Oleksandr Hryvul

This article is part of our Christian Terms catalog, exploring words and phrases of Christian theology and history. Here are some of our most popular articles covering Christian terms to help your journey of knowledge and faith:

The Full Armor of God

The Meaning of "Selah"

What Is Grace? Bible Definition and Christian Quotes

What is Discernment? Bible Meaning and Importance

What Is Prophecy? Bible Meaning and Examples

.jpg)