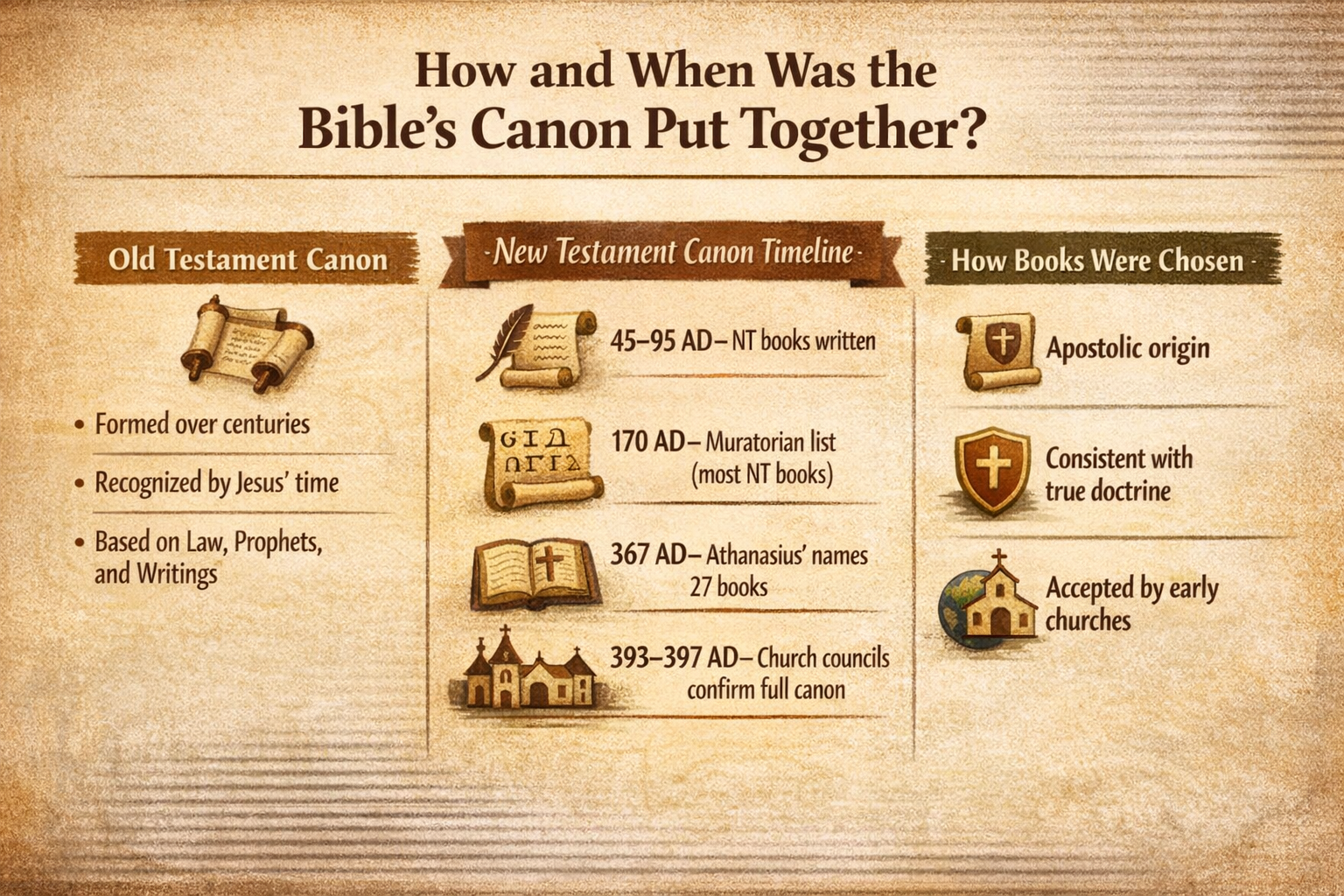

The canon of the Bible was formed over centuries as early believers recognized which books were truly inspired by God. The Old Testament was largely settled by Jesus’ time, while the New Testament canon was affirmed by the 4th century, based on apostolic authority, consistency, and widespread use in the early church.

The Bible stands as a foundation of Christian life and belief. Yet the Bible didn’t always exist. At some point, Christians chose and organized the books and writings that ended up in the Bible. We call that collection the canon. The term canon comes from the Greek kanon, meaning “rule” or a “measuring stick,” and refers to any officially recognized collection of authoritative writings for a religion or group. Christians believe and affirm the Bible is divinely inspired by God to serve as a foundation for faith, doctrine, and practice.

God inspired these texts, but how did Christians almost two thousand years ago decide what went into the canon? What can we learn from the process?

What Is the Septuagint and Its Influence on Scripture?

We must first look at the legacy of the Hebrew Septuagint.

The Septuagint, sometimes known as LXX, was developed in the third century BC in Alexandria, Egypt. According to Jewish tradition, seventy (or seventy-two) Jewish scholars painstakingly translated the first five books of the Old Testament, the Torah, from Hebrew into Greek (the common and new academic language) under King Ptolemy II. Over time, Jews translated other writings of history, prophecy, wisdom, and more.

Most Jews lived in a Greek-speaking world three centuries before Jesus and didn’t really understand Hebrew. The Greek translation made sure they could still access their sacred writings, essential to remaining faithful to God and his ways while dispersed from Judea and Jerusalem. Eventually, the Septuagint became the established core collection of Hebrew writings for faith and tradition, essentially the Jewish “canon.”

Jesus and the disciples grew up with this idea of the Hebrew canon in the Septuagint. It was read in synagogues and quoted by Jewish teachers. In Judea, they mainly spoke Aramaic but were more familiar with the Greek translation. When Jesus and his apostles referred to Scripture, they usually quoted from the Septuagint Greek rather than the original Hebrew. As an example, Jesus reads from Isaiah in the synagogue (Luke 4:18-19), and the words align more with the Greek translation than the Hebrew texts. Paul and the other New Testament authors wrote in Greek and used the Septuagint in their letters.

When the New Testament refers to the importance of Scripture, they almost exclusively mean the Septuagint. They used the Old Testament canon to teach the New Covenant and Jesus as Messiah.

Therefore, Christianity already had experience with a library of canonical writings as foundational to faith. With the Septuagint as a precedent, it wasn’t much of a stretch for early Christians to begin collecting their own writings and thinking of some as God-inspired. Just as the Greek-speaking Jews adopted a translation and chose certain books to serve as canon, the early church started compiling their own central books to use for faith and practice.

What criteria did the early church use to choose these books and letters for the canon? We must first look at why the apostles wrote things down in the first place.

What Was the Purpose of the Different Writings in the New Testament?

Jesus didn’t write any of his teachings down. He discipled people, sharing his doctrine with a few select men we call the apostles. After his resurrection and before his ascension, he gave his disciples (and, by extension, all Christians) the following mission: “Go and make disciples of all nations … teaching them to obey everything I have commanded you.” (Matthew 28:19-20) The apostles took this seriously, as we see in Acts, teaching, preaching, and planting churches.

Their writings, therefore, flowed from this commission to make disciples. The Pax Romana, a time of peace, and the Roman administrative system allowed for easy written communication between churches as Christianity expanded. The common language of Greek also helped spread the Gospel message to people of all nations.

The apostles told the same stories over and over to teach about the Messiah, and the Gospels were written to preserve these accounts and spread them easily. Each Gospel had a specific audience and purpose. These writings solidified Jesus’ words and actions for the expanding church and any who sought to believe.

The apostles wrote letters to guide and teach the early churches. Paul’s letters addressed theological issues and errors and included encouragements for practical living based on heavenly truth. James, Peter, John, and Jude wrote letters with doctrinal teaching to strengthen the church in times of persecution. They called Christians to holiness and taught them how to obey Jesus’ commands in a hostile world.

The apostles didn’t necessarily set out to create a new Bible. They obeyed Christ’s call to spread his teachings and to disciple others to live in the faith. And since the New Covenant expanded the Old Testament writings, realizing the Hebrew promises for the Messiah and the Kingdom of God, the apostles had to explain this new Spirit-filled life to others.

With the Septuagint’s precedent, Christians of the second century started choosing certain writings and letters as God-inspired, beginning the development of a new canon. What were their criteria?

What Were the Three Criteria for Early Church Biblical Canonization?

The early church had a challenge regarding which writings were authoritative. While many people remained illiterate, a large portion could read Greek. The Greco-Roman philosophical culture encouraged writings on important subjects to spread messages or teachings. Therefore, many writings existed from the “Christian” or religious community. Additionally, some writers would put a famous person’s name on their letter or book to encourage a wider audience to accept it. Some letters with Peter or John’s name might be falsely attributed to them. So the early church established three main criteria to determine what new writings would be included in the canon.

- First, the early church chose writings that came from the apostles or from those closely connected to them. The apostles witnessed Jesus’ ministry, resurrection, and teachings first-hand, and Jesus directly commissioned them to spread his message. The early church believed these men had a unique role, so they counted their writings as authoritative. Early church leaders needed to prove authorship, however. Books like the Gospel of Thomas and Peter emerged and circulated, but the church rejected them as canonical because they couldn’t prove Thomas or Peter actually wrote them. The four Gospels, for example, were accepted because of their direct connection with Jesus. Matthew and John were apostles Mark recorded Peter’s teachings, and Luke based his Gospel on Paul’s teachings. Paul’s letters were recognized because the church believed him called as an apostle by Jesus directly, hence his encounter with Christ being repeated in Acts. Other writings lacking apostolic authorship were set aside or perhaps even rejected.

- Second, also related to Jesus’ commission, the early church examined whether the writing aligned with “apostolic doctrine.” Some letters from Paul or others might exist, but did they communicate the right doctrine? Apostolic doctrine refers to the core teachings from Jesus passed down to the apostles. This doctrine would have included truths like Jesus’ divine and human nature, his bodily resurrection, and salvation by grace to live holy. If a text didn’t teach this doctrine or included something opposed to the faith, it was excluded. As an example, only Gospels that included the death and resurrection accounts were accepted, core to the message and work of Jesus. The Gospel of Judas not only didn’t include those accounts but taught ideas contrary to apostolic doctrine, like denying Jesus’ death for sin. The church leaders rejected the Gospel of Judas. In this way, from several different sources and testimonies, the universal teaching of Jesus was expressed in a consistent manner.

- Third, the whole church across all regions needed to recognize a book as necessary for the faith. Jesus’ apostolic commission was to produce a righteous, holy people, disciples who lived a Spirit-filled life in obedience to Christ. Paul mentions in 1 Corinthians 14 how when prophets spoke, the church could and should bear witness to whether the message came from God or not, because the Spirit dwells within the church individually and collectively. The Spirit would bear witness. This happened with the choosing of canonical books. The church bore witness to what letters or books were inspired by the Spirit, and further, which developed and produced Jesus disciples. By the second century, the early church was spread throughout the Roman Empire. But believers and leaders across languages and cultures affirmed the same core writings as Scripture. Church leaders paid attention to which writings were useful in worship and teaching. If a book was widely accepted by churches from Jerusalem to Rome or North Africa, it indicated the Spirit had guided its acceptance, along with the Old Testament. What we know as the New Testament wasn’t chosen by a single person or group but developed and recognized over time by the entire body of Christ. The canon wasn’t imposed by an administrative body but acknowledged through spiritual discernment.

How Did the Council of Nicaea Shape the Biblical Canon?

Many people believe the biblical canon was decided by Rome or the Council of Nicaea in AD 325. However, the New Testament was largely established long before Nicaea. By 325, only a couple books remained in question, and even those weren’t debated at the council.

As we’ve noted, the Septuagint, or the Old Testament canon, had been established a century or more before Jesus. And the early church adopted the Septuagint as Scripture. The New Testament canon was almost complete by the late second century.

Early church leaders like Irenaeus (AD 180) and Tertullian (AD 200) affirmed the four Gospels, Acts, Paul’s letters, and other apostolic writings as Scripture, and this during a time of great persecution against the church from Rome. The Muratorian Fragment (AD 170) lists most of the New Testament books as authoritative, showing the church had already chosen core writings. By the early third century, Origen and other scholars acknowledged the majority of what we know as the New Testament. Based on the criteria above, the only two books in question were James and Hebrews.

James was questioned because a few believed it conflicted with Paul’s teaching on faith and grace alone. They never questioned James’ authorship, however. Eventually, the church recognized it as consistent with Paul’s writings on how faith would lead to right living. Hebrews faced questions because the early church couldn’t confirm the author. But Hebrews’ theology proved absolutely consistent with apostolic teaching and didn’t claim to come from a false author. So it was included as it is today.

At no point did the Council of Nicaea address biblical canon. Emperor Constantine gathered Christian bishops to settle a major doctrinal issue—the Arian controversy, which dealt with Christ’s dual divine and human nature. But the books of the New Testament were already being read in churches across the empire. No emperor or government imposed the canon.

The New Testament canon happened organically and spiritually through the church to fulfill Jesus’ commission to teach his doctrine and pass it down to other disciples. If we can point to a date for the final canon, we can say between 200-250 AD, far before Rome started to see the benefit of Christianity. On the contrary, around 250 AD Rome still persecuted the church. In AD 397, the Council of Carthage only confirmed what the church already established more than a century before.

The full biblical canon emerged from the apostles following and fulfilling Jesus’ commission, and the church identified the writings carrying that apostolic authority, a faithful witness to the Word of God.

Peace.

Further Reading:

What is the Biblical Canon and Why Should Christians Know about It?

The Biblical Canon: How Was the Bible Canon Chosen?

Photo credit: ©Getty Images/Red Goldwing

.jpg)