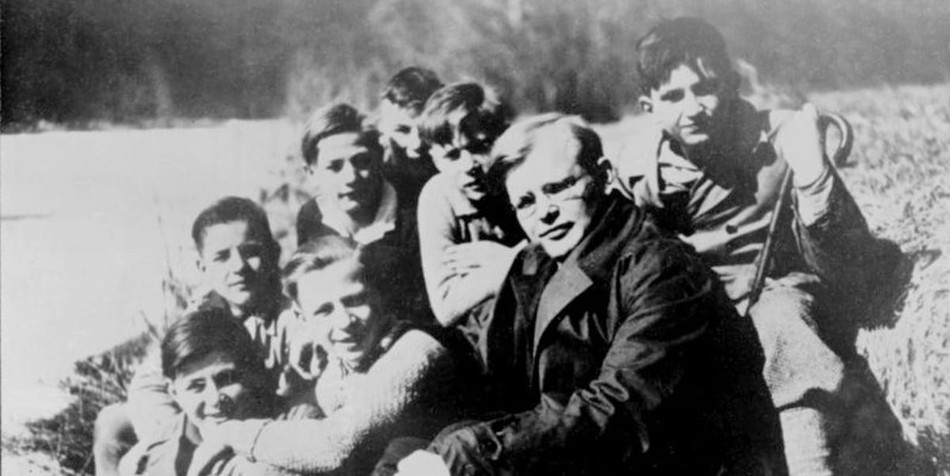

February 4 marks the birthday of German theologian and resistance fighter Dietrich Bonhoeffer (1906-1945). Whether you discovered him from reading his classic book The Cost of Discipleship or learned his story from Eric Metaxas’ book Bonhoeffer: Pastor, Martyr, Prophet, Spy, his story is just as inspiring and thought-provoking over 70 years after his death. Particularly in an age where many people worry about governments taking away liberties and churches ponder when to resist secular authority, Bonhoeffer’s life and work are worth studying.

Bonhoeffer’s Early Life

Dietrich Bonhoeffer was born February 4, 1906, in Breslau, Germany. He had seven siblings, including a twin sister, Sabine. His oldest brother, Walter, died in 1918 while fighting in World War I. The Bonhoeffers were a well-to-do family with a good pedigree – his mother Paula came from aristocrats, his father Karl was a nationally-regarded psychiatrist at Berlin’s Charité Hospital.

While his maternal grandfather and great-grandfather were theologians, Bonhoeffer didn’t grow up in a family of regular churchgoers. His parents and siblings were surprised when 14-year-old Dietrich announced that he wanted to be a theologian. Some writers (such as David P. Gushee and Colin Holtz in Moral Leadership for a Divided Age) have suggested this choice initially had more to do with Bonhoeffer setting himself apart from his siblings.

Bonhoeffer started his theology studies in 1923 at the University of Tübingen. After finishing his pre-doctorate degrees, he went to Humboldt University of Berlin, getting his doctorate in 1927. Bonhoeffer was only 21 years old when he achieved this degree, an excellent student who impressed acclaimed teachers like Luther expert Karl Holl and church historian Adolf von Harnack. However, Bonhoeffer admitted later that he rarely attended church and prayed little during this time, even as he planned to become a pastor.

Bonhoeffer’s Spiritual Turning Point

Regulations meant that Bonhoeffer couldn’t receive ordination until he was twenty-five. In 1930, after working as an assistant pastor in Barcelona, Bonhoeffer filled out his last year of ineligibility in New York. He attended Union Theological Seminary, studying under the noted theologian Reinhold Niebuhr. However, Bonheoffer wasn’t impressed with his classes, saying, “there is no theology here.”

African-American seminary student Frank Fisher introduced Bonhoeffer to Harlem’s Abyssinian Baptist Church, which had a more positive effect. Bonhoeffer loved the church’s emphasis on preaching the gospel, its worship culture, and its focus on helping the poor. Seeing the congregants face racism disgusted him, and he learned to see Jesus in the context of suffering minorities. When Bonhoeffer returned to Germany, many noticed a change. He replied, “I became a Christian in America.”

In 1931, Bonhoeffer started teaching systematic theology at the University of Berlin. The same year, he served as a youth secretary at the World Alliance for Promoting International Friendship Among the Churches. He was ordained in November 1931 and taught both seminary classes for adults and confirmation classes for younger people. One student interested in confirmation was Maria von Wedemeyer, an 11-year-old girl from a similarly aristocratic German background. Bonhoeffer decided that she was “too immature” but accepted her brother and several cousins as students.

Bonhoeffer Facing the Nazis

On January 30, 1933, Bonhoeffer’s career took a sharp turn: Adolf Hitler became chancellor of Germany. On February 1, Bonhoeffer gave a radio speech warning Germans not to idolize their new Führer. His speech was cut off in the middle of a sentence.

The following months made it clear that the Nazi Regime wanted German Protestant churches to get behind one set of policies, particularly promoted by the Deutsche Christen movement. These policies included nationalist theology that treated the Führer as the church’s leader, under-emphasizing or banning the Old Testament, and adding “the Aryan clause” to church bylaws to bar Jews from church leadership.

Bonhoeffer and hundreds of other pastors refused to follow this line, backing Swiss theologian Karl Barth’s Barmen Declaration that affirmed Christ led the church. Fights and schisms followed, and Christians opposing Nazi policies founded the Confessing Church in 1934.

Bonhoeffer Gets a Chance to Escape

In 1935, Bonhoeffer was in England, talking to Barth. Bonhoeffer had accepted a post to pastor two churches there, using connections in England to help the Confessing Church. However, he admitted to Barth that he was tired of fighting with little support. He was considering staying in England, away from the conflict. Barth replied, “And what of the German Church?”

Shortly afterward, Bonhoeffer declined an opportunity to study under Gandhi in India and returned home. From 1935-1937, he taught at the Confessing Church’s underground seminary in Finkenwalde. He reworked lectures from this period into The Cost of Discipleship, a 1937 book criticizing “cheap grace,” and affirmed Christians make sacrifices to follow Christ’s example.

In 1936, authorities banned Bonhoeffer from teaching at the University of Berlin. His father Karl retired from his hospital that year, possibly to avoid backing state-enforced sterilization procedures. Nazis shut down the Finkenwalde underground seminary in 1937. In 1938, Sabine and her Jewish-born husband fled to England, and authorities announced that every German pastor had to swear loyalty to Hitler.

Reinhold Niebuhr provided Bonhoeffer a new escape route, a chance to return to Union Theological Seminary. Bonhoeffer came to New York in June 1939, then returned to Germany two weeks later. Many were upset that he turned down a golden opportunity, but he explained in a letter to Niebuhr:

“I will have no right to participate in the reconstruction of Christian life in Germany after the war if I do not share the trials of this time with my people.”

The same year, Bonhoeffer released a book about Christian community, informed by his experiences at Finkenwalde: Life Together. Then in August 1939, he did something which seemed to violate all his anti-Nazi principles: he joined Germany’s military intelligence group, the Abwehr.

Bonhoeffer and the Plot to Kill Hitler

Officially, Bonhoeffer said he joined the Abwehr to avoid conscription, plus his overseas church connections made him an asset, and his brother-in-law Hans von Dohnányi was in it. The truth was that Abwehr’s leader Wilhelm Canaris and other operatives were resisting the Nazis and planning Hitler’s death.

From 1939-1943, Bonhoeffer completed various secret missions for the German resistance, seeking overseas help. He began writing Ethics, a book on morals from a Christ-centered (or Christological) perspective. He hoped it would be his greatest work.

Something more personal, and perhaps more shocking than everything else, happened in January 1943. Bonhoeffer had stayed in contact with the von Wedemeyers since the 1930s, and Maria von Wedemeyer had grown into a mature young woman. Despite the age difference (she was 18, he was 36), they became engaged. Renate Bethge, the fiancée of Bonhoeffer’s friend and successor Eberhard Bethge, wrote later that she was happy for the couple but could see that the engagement surprised many.

The joy was short-lived. In April 1943, Bonhoeffer was arrested for helping smuggle 14 Jews out of Germany. He spent 18 months awaiting trial in Tegel Prison, writing and ministering to fellow prisoners. One guard tried to help Bonhoeffer escape, but he declined because the Nazis might have taken it out on family members.

Bonhoeffer at His Life’s End

On July 20, 1944, an assassination attempt against Hitler titled “Operation Valkyrie” failed. Nazis rounded up many Abwehr officials and German resistance fighters in the aftermath, including Dohnányi and Bonhoeffer’s brother Klaus.

Charged with knowing about the plot, Bonhoeffer was transported through several prisons until, in February 1945, he landed in Buchenwald Concentration Camp. Moved to Flossenbürg Concentration Camp a few days later, Bonhoeffer performed a church service in a derelict schoolhouse for other prisoners.

On April 8, 1945, he was court-martialed without representation and sentenced to death. The next day, Bonhoeffer, Wilhelm Canaris, and five other men were ordered to strip naked before being hanged. Hermann Fischer-Hüllstrung, a Flossenbürg prison doctor, described Bonhoeffer’s last moments:

“Through the half-open door, I saw Pastor Bonhoeffer still in his prison clothes, kneeling in fervent prayer to the Lord his God. The devotion and evident conviction of being heard that I saw in the prayer of this intensely captivating man moved me to the depths.”

Bonhoeffer’s last words were, “this is… for me, the beginning of life.” His brother-in-law was executed the same day in Sachsenhausen camp. His brother Klaus was executed on April 23. On April 30, Hitler committed suicide, and on May 7, Germany surrendered.

All told, four of Bonhoeffer’s siblings outlived him. Sabine lived the longest, dying in 1999. Maria von Wedemeyer studied mathematics at the University of Göttingen and moved to the United States in 1948. She had a successful career as a computer scientist, married and divorced twice, and had three children. She died in 1977. Her last letters to Bonhoeffer were published in 1994 as Love Letters from Cell 92.

Bonhoeffer’s Legacy

Many remember Bonhoeffer’s sacrifices, the way he resisted Hitler, rescued Jews, and stood against government attempts to subvert orthodox Christianity. His books Life Together and the Cost of the Discipleship are spiritual classics.

His later work – the unfinished Ethics and the poems, unfinished fiction, and essay fragments he wrote in prison – still inspire debate. His prison writings describe a future age that would need a “religionless Christianity,” a term that Bonhoeffer didn’t live long enough to explain. In a chapter on Bonhoeffer for The History of Apologetics, Matthew D. Kirkpatrick argues that whether Bonhoeffer’s ideas changed or not in prison, these later writings show him sobered, less interested in the abstract.

Regardless of which side we best connect with – Bonhoeffer’s life, the early writings, or the later writings – he was a courageous man who refused to have anything but God. His stance for truth and against tyranny continues to inspire today.

Further Learning:

To learn more about Bonhoeffer, enjoy this video where Eric Metaxas discusses his 2012 book Bonhoeffer: Pastor, Prophet, Martyr, Spy.

Or read the following:

Dietrich Bonhoeffer: The Cost of Discipleship

Bonhoeffer Executed on Hitler's Order

Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons/German Federal Archives

This article is part of our People of Christianity catalog that features the stories, meaning, and significance of well-known people from the Bible and history. Here are some of the most popular articles for knowing important figures in Christianity:

How Did the Apostle Paul Die?

Who are the Nicolaitans in Revelation?

Who Was Deborah in the Bible?

Who Was Moses in the Bible?

King Solomon's Story in the Bible

Who Was Lot's Wife in the Bible?

Who Was Jezebel in the Bible?

Who Was the Prodigal Son?