For seven years, the money to send a missionary to Liberia lay unused. The mission committee could find no one willing to take the risk.

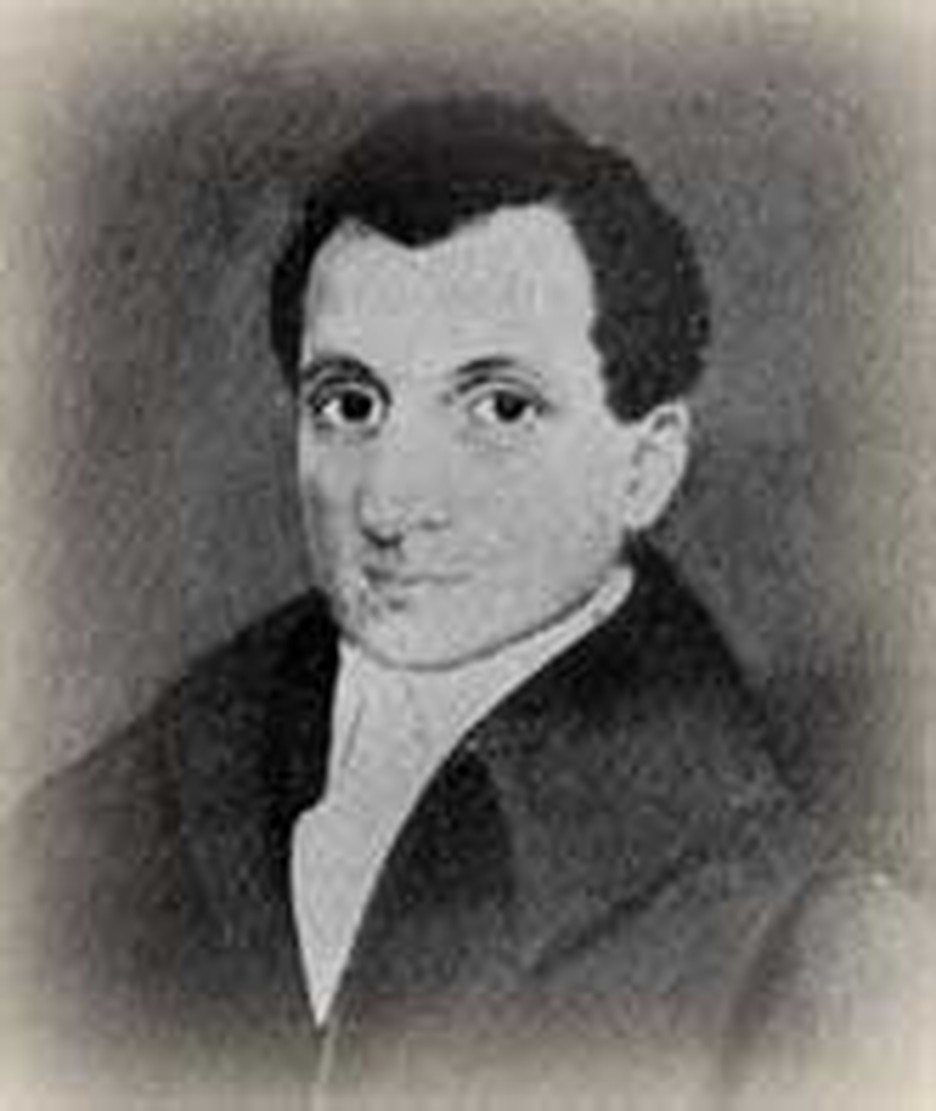

They could find no one, that is, until Melville Cox stepped forward. Deathly ill with tuberculosis, he could speak only with pain. In 1830 his wife, baby and several close family members had died within a short span, devastating him, but releasing him from ties that might have held him back. Now his heart burned with desire to carry the gospel to people who had never before heard it.

"If you go to Africa, you'll die there," warned a student at Connecticut's Wesleyan University.

"If I die in Africa, you must come and write my epitaph," retorted Melville Cox. He felt that it would be no loss to die far from home (as long as Christ were with him) but hoped that his death would spur forward the cause of mission work. Even his epitaph should reflect that spirit.

"What shall it be?" asked the student.

Melville's reply became a blazing torch to kindle Methodist enthusiasm for missions. "Let a thousand die before Africa be given up!" he exclaimed.

He sailed for Liberia aboard the Jupiter on this day, November 6, 1832--the first missionary sent to a foreign field by America's Methodists. While sailing, he made plans, but recognized that their accomplishment was not up to him. "In making up my mind and in searching for a passage to go out, I have followed the best light I could obtain. I now leave it all with God..." The following March, he thanked God he had finally arrived in Liberia.

He immediately visited the area's few Christians, gathered them into an assembly, started a church, and began writing Sketches of West Africa. He opened a school and taught seventy students. But, as had been predicted, his health did not hold out. He contracted malaria. He could have returned home on the ship Hilarity after his first attack of the deadly tropical disease which sent shooting pains through him, but he chose to remain.

His last journal entry, written June 26, 1833, noted that it had been four days since he had seen a doctor. "This morning I feel as feeble as mortality can well. To God I commit all." Despite his weakened state, he survived almost another month, not dying until July 21, 1833, four and a half months after his arrival.

During one of his fevers, he sang a spiritual, "I am happy! I am happy!...My days are immortal..." This triumphant spirit made his story a powerful tool for recruiting additional missionaries.

Bibliography:

- "Cox Memorial United Methodist Church, Hallowell, Maine." https://www.gcah.org/Heritage_Landmarks/Cox.htm

- "Genealogical Information from the Western Methodist, 1833-1834." https://www.tngenweb.org/madison/smith/wm33-04.htm

- "Melville Beveridge Cox." Edited Appleton's Encyclopedia. https://www.famousamericans.net/melvillebeveridgecox/

- Morgan, Robert J. On this Day. Nashville: T. Nelson, 1997.

- Smith, Larry D. "Before Africa Be Given Up!" https://www.gbs.edu/revivalist/0104_editorial.shtml

- Taylor, S. Earl. The Price of Africa. New York: Young People's Missionary Movement, 1902.

Last updated July, 2007.

.jpg)