The Greatest Thing in the World! What is it? What Do You Say?

Great faith? A big job? Superior Education? Being liked? Passion? Love? Being smart? Athletic prowess? Respectability? Wealth? hope?

So, what did you say was "the greatest thing in the world?"

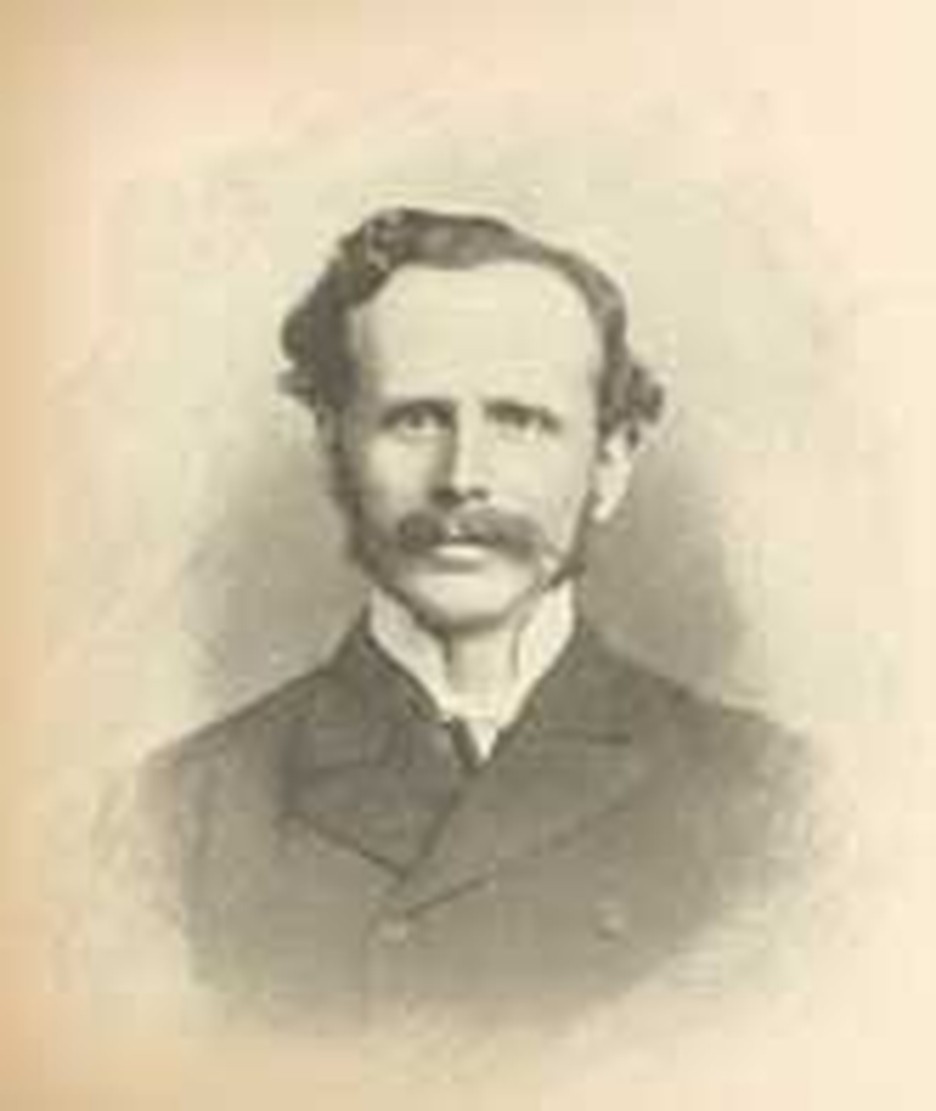

Scotsman Henry Drummond insisted he knew the answer based on what he considered the highest authority. He spoke of the "greatest thing" often. In fact he was invited all over the world to talk about it. The title of his little talk was simply The Greatest Thing in the World. You can read it in ten or fifteen minutes. It has never been out of print in the 120 years since first published and maintains its status as a classic of spiritual inspiration.

What did Henry say was the greatest thing? You probably guessed it:

The greatest thing in all the world is Love.

What follows is just a taste from Drummond's classic talk.

Every one has asked himself the great question of antiquity as of the modern world: What is the . . . noblest object of desire, the supreme gift to covet?

We have been accustomed to be told that the greatest thing in the religious world is Faith. That great word has been the keynote for centuries of the popular religion; and we have easily learned to look upon it as the greatest thing in the world. Well, we are wrong. If we have been told that, we may miss the mark. I have taken you, in the chapter which I have just read [Editor’s note: he always began his talk by reading I Corinthians 13], to Christianity at its source; and there we have seen, "The greatest of these is love." It is not an oversight. Paul was speaking of faith just a moment before. He says, "If I have all faith, so that I can remove mountains, and have not love, I am nothing." So far from forgetting, he deliberately contrasts them, "Now abideth Faith, Hope, Love," and without a moment's hesitation, the decision falls, "The greatest of these is Love."

And it is not prejudice. A man is apt to recommend to others his own strong point. Love was not Paul's strong point. The observing student can detect a beautiful tenderness growing and ripening all through his character as Paul gets old; but the hand that wrote, "The greatest of these is love," when we meet it first, is stained with blood.

Nor is this letter to the Corinthians peculiar in singling out love as the summum bonum. The masterpieces of Christianity are agreed about it. Peter says, "Above all things have fervent love among yourselves." Above all things. And John goes farther, "God is love." And you remember the profound remark which Paul makes elsewhere, "Love is the fulfilling of the law." Did you ever think what he meant by that? In those days men were working their passage to Heaven by keeping the Ten Commandments, and the hundred and ten other commandments which they had manufactured out of them. Christ said, I will show you a more simple way. If you do one thing, you will do these hundred and ten things, without ever thinking about them. If you love, you will unconsciously fulfill the whole law. . . . "Love is the fulfilling of the law." It is the rule for fulfilling all rules, the new commandment for keeping all the old commandments, Christ's one secret of the Christian life.

Now Paul had learned that; and in this noble eulogy he has given us the most wonderful and original account extant of the summum bonum. We may divide it into three parts. In the beginning of the short chapter, we have Love contrasted; in the heart of it, we have Love analyzed; towards the end we have Love defended as the supreme gift.

. . . .To love abundantly is to live abundantly, and to love for ever is to live for ever. Hence, eternal life is inextricably bound up with love. We want to live forever for the same reason that we want to live tomorrow. Why do you want to live tomorrow? It is because there is someone who loves you, and whom you want to see tomorrow, and be with, and love back. There is no other reason why we should live on than that we love and are beloved. It is when a man has no one to love him that he commits suicide. So long as he has friends, those who love him and whom he loves, he will live; because to live is to love. Be it but the love of a dog, it will keep him in life; but let that go and he has no contact with life, no reason to live. The "energy of life" has failed. Eternal life also is to know God, and God is love. This is Christ’s own definition. Ponder it. "This is life eternal, that they might know Thee the only true God, and Jesus Christ whom Thou hast sent." Love must be eternal. It is what God is. On the last analysis, then, love is life. Love never faileth, and life never faileth, so long as there is love. That is the philosophy of what Paul is showing us; the reason why in the nature of things Love should be the supreme thing -- because it is going to last; because in the nature of things it is an Eternal Life. That Life is a thing that we are living now, not that we get when we die; that we shall have a poor chance of getting when we die unless we are living now. No worse fate can befall anyone in this world than to live and grow old alone, unloving, and unloved. To be lost is to live in an unregenerate condition, loveless and unloved; and to be saved is to love; and he that dwelleth in love dwelleth already in God. For God is love.

The Challenge

How many of you will join me in reading I Corinthians 13 once a week for the next three months? . . . It is for the greatest thing in the world. You might begin by reading it every day, especially the verses which describe the perfect character. "Love suffereth long, and is kind; love envieth not; love vaunteth not itself." Get these ingredients into your life. Then everything that you do is eternal. It is worth doing. It is worth giving time to. No man can become a saint in his sleep; and to fulfil the condition required demands a certain amount of prayer and meditation and time, just as improvement in any direction, bodily or mental, requires preparation and care. Address yourselves to that one thing; at any cost have this transcendent character exchanged for yours. You will find as you look back upon your life that the moments that stand out, the moments when you have really lived, are the moments when you have done things in a spirit of love.

Moody and Drummond

Drummond was greatly beloved by evangelist D. L. Moody who sought his companionship and help. After Moody's 1884 campaign in England, he was relaxing with 21 of his fellow workers. The group urged Moody to give a devotional, but the great evangelist demurred: "No, you've been hearing me for eight months, and I'm quite exhausted. Here's Drummond, he will give us a Bible reading." Somewhat reluctantly, Drummond arose, pulled from his hip pocket a Testament and began to read I Corinthians 13. Without a note he expounded a message of which Moody said: "It seemed to me that I had never heard anything so beautiful, and I determined not to rest until I brought Henry Drummond to Northfield to deliver that address." Indeed, Moody wished the message could be read in his Northfield schools once a year and "read once a month in every church 'til it was known by heart."

The Remarkable Henry Drummond

Over a century has passed since the death of Henry Drummond, the Scottish professor whose writings stirred the English-speaking world of the latter 19th century. A modest, world-aware man of unselfconscious piety, before his compressed lifetime ended at the age of 46, March 11, 1897, he had become: a great friend of Dwight L. Moody, who said Drummond "is the most Christ-like man I ever met"; a convincing speaker, once called "the greatest leader of young men this century has seen," because of his effectiveness with university students and his devotion to the work of the Boys Brigade; a Great Commission-believer, unafraid of modern science; one of the earliest evangelical authors to gain wide popular appeal. For these reasons and more, this modest servant -- today most famous as author of a remarkable little essay on I Corinthians 13, The Greatest Thing in the World -- deserves a special place in Christians' memory.

Warmly accepted in three visits to the United States (1879, 1887, 1893), Henry Drummond was welcomed among Ivy League institutions and others. Amherst College granted him an honorary doctorate. When he departed Harvard after speaking to crowds of impressed undergraduates, Professor Peabody analogized that Drummond’s appearance there was “as though a comet had flashed upon the view and had left a trail of light as it sank below the horizon.” A Boston newspaperman wrote in 1893, "Next to the death of Phillips Brooks, the event which stirred Boston religious circles most profoundly last winter was the presence in the city for two months of Professor Henry Drummond." Of the young Scot's time at Yale, William Lyon Phelps, no stranger to the speaker's rostrum, opined, "I have never seen so deep an impression made on students, by any speaker on any subject."

Chautauqua's audience found Drummond to be "a worldwide celebrity" whose "modesty was phenomenal." After the first of his Lowell Lectures at Lowell Institute in 1893, he was compelled to a repeat performance of each address in the series, so packed was the hall, and so great was the demand to hear him. On his visits, the American public dazzled Drummond with offers of presidencies of colleges, invitations to address major institutions and societies, and competing bids among lecture bureaus.

Unaccustomed to such attention, the 35-year-old sensation wrote his parents from the U.S. (July 1, 1887): "I am tearing away here at American speed. Already I have been asked to become principal of a college, ditto of another college, to write for various papers, to lecture in half the states of the Union, and otherwise to line my pocket with dollars. But I have refused all wiles...." -- from an article by Thomas E. Corts and Marla H. Corts

Sorry Guys. Some Other Time.

Although only 28 years old at the time, Drummond, while visiting America, was invited to dinner with the famous poets, Oliver Wendell Holmes and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, but he turned them down, preferring instead to travel 800 miles to visit evangelist D. L. Moody.