Many of the early Puritans and pilgrims arrived in America with a fervent faith and vision for establishing a godly nation. Within a century the ardor had cooled. The children of the original immigrants were more concerned with increasing wealth and comfortable living than furthering the Kingdom of God. The same spiritual malaise could be found throughout the American colonies. The philosophical rationalism of the Enlightenment was spreading its influence among the educated classes; others were preoccupied with the things of this world.

When Theodore Frelinghuysen, a minister of the Dutch Reformed Church, came to begin his pastoral world in New Jersey during the 1720's, he was shocked by the deadness of the churches in America. He preached the need for conversion, a profound, life-changing commitment to Christ, not simply perfunctory participation in religious duties. Presbyterian Gilbert Tennent was heavily influenced by Frelinghuysen and brought revival to his denomination. Tennent believed the deadness of the churches was in part due to so many pastors having never been converted themselves. His book On the Dangers of an Unconverted Ministry caused quite a stir!

Origins of the Great Awakening

The event that has become known as the Great Awakening actually began years earlier in the 1720s. And, although the most significant years were from 1740-1742, the revival continued until the 1760s.

Many of the early colonists had come to the new world to enjoy religious freedom, but as the land became tamed and prosperous they no longer relied on God for their daily bread. Wealth brought complacency toward God. As a result, church membership dropped. Wishing to make it easier to increase church attendance, the religious leaders had instituted the Halfway Covenant, which allowed membership without a public testimony of conversion. The churches were now attended largely by people who lacked a personal relationship with Jesus Christ. Sadly, many of the ministers themselves did not know Christ and therefore could not lead their flocks to the true Shepherd. Then, suddenly, the Spirit of God awoke as though from an intense slumber and began to touch the population of the colonies. People from all walks of life, from poor farmers to rich merchants, began experiencing renewal and rebirth.

The faith and prayers of the righteous leaders were the foundation of the Great Awakening. Before a meeting, George Whitefield would spend hours--and sometimes all night--bathing an event in prayers. Fervent church members kept the fires of revival going through their genuine petitions for God's intervention in the lives of their communities.

The early rays of the Great Awakening began with Theodore Frelinghuysen of the Dutch Reformed Church in New Jersey. Through his ministry, the hearts of his church members were changed. It was the young people who responded first and experienced the regeneration of becoming new creations. They, in turn, spread the message to their elders. Thus began the first spark of the Great Awakening.

In 1727, about the time that Frelinghuysen and Tennent were seeing a revival in New Jersey, Jonathan Edwards went to Northampton, Massachusetts to become assistant minister to his grandfather Solomon Stoddard. Stoddard had ministered at Northampton almost sixty years and during that time had seen five periods of revivals or "harvests," as he called them. Stoddard recognized that a church goes through periods of spiritual refreshing and depression: There are some special Seasons wherein God doth in a remarkable Manner revive Religion among his People. God doth not always carry on his work in the church in the same proportion...there be times wherein there is a plentiful Effusion of the Spirit of God, and Religion is in a more flourishing Condition.

Jonathan Edwards, Father of the Great Awakening

Pictured Above: Portrait of Jonathan Edwards

The preacher's monotone voice filled the church in Northampton, Massachusetts. As the brilliant Jonathan Edwards spoke, he kept his eyes focused on the back wall of the church. Gently, Edwards' words began to sink into the hearts of the assembly, and although his method of speaking lacked enthusiasm, his words were powerful. Revival followed.

During the 1730s, the church in Northampton felt the stirring of the Holy Spirit, moving them from their lukewarm apathy to an awakening of their souls. Delivering his most famous sermon, "Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God," on July 8, 1741, in Enfield, Connecticut, Edwards helped spread the revival. A great commotion swept over the people and they began wailing, crying, and screeching loudly. Frequently Edwards asked the congregation to control themselves so he might finish his sermon. As a result of his preaching and the work of the Spirit, lives began to change and complete towns were transformed.

The most prominent theologian of the Great Awakening was Jonathan Edwards. Not a powerful speaker, Edwards still managed to spread the revival. From his brilliant mind, he constructed one of the most impressive sermons ever preached. He also wrote many books and pamphlets describing the events he saw in his own church. The only son in a family of eleven children, Edwards was born on October 10, 1703. At the young age of thirteen, he entered Yale (not unusual during that era of history) and graduated in 1723. Four years later Jonathan married the remarkable and virtuous Sarah Pierpont. Faithfully Sarah helped Edwards in his ministry and personal endeavors. In 1727, Edwards became the assistant minister at the Northampton church. When his grandfather, Solomon Stoddard, died, Jonathan became the minister and served in that church for nearly twenty-four years. He spoke boldly against the Halfway Covenant. Since many of the members who promoted the Halfway Covenant were merchants (or river gods, as Edwards called them), they were able to make most of the decisions for the community, thus giving them the power over the rest of the populace. Edwards did much to help alleviate the tyrannical practices that followed.

In the 1730's, when Jonathan Edwards became the minister at Northampton, he found only spiritual deadness in the church. He was concerned about the immorality of the young people and began visiting them in their homes. In 1734 he preached a series of sermons on justification by faith alone. "By December," wrote Edwards, "the Spirit of God began extraordinarily to set in. Revival grew, and souls did as it were come by floods to Christ." Over a six month period, Edwards recorded three hundred conversions. He wrote a book, Narratives of Surprising Conversions, describing the revival and its effects on the life of the town.

The Far-Reaching Revival

In his Treatise Concerning Religious Affections, Edwards emphasized that true religion must affect the heart. In The Distinguishing Marks of a Work of the Spirit of God, Edwards taught from I

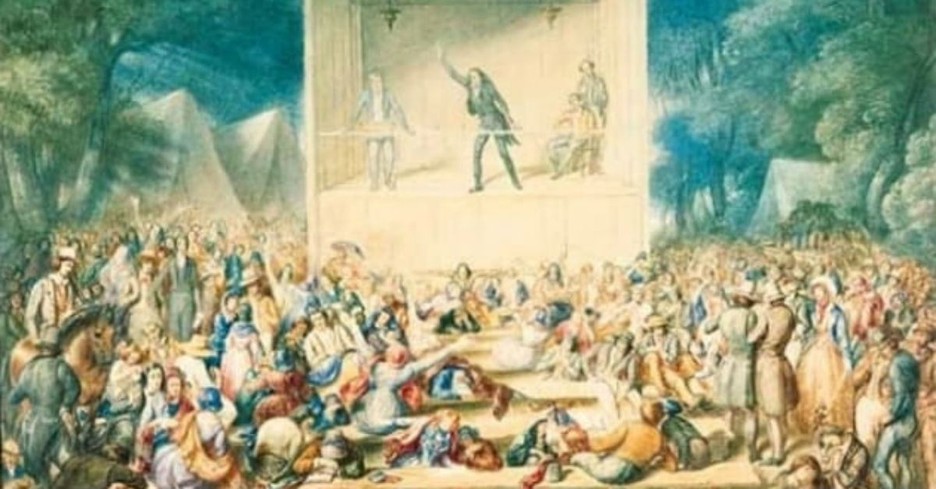

Great Awakening Crowds - the people came "en mass"

George Whitefield, an Anglican evangelist and friend of John and Charles Wesley, not only traveled throughout Britain bringing the gospel of Christ, but he also made seven trips to America between 1738 and 1770. He was probably the most well-traveled man in the colonies and drew large crowds wherever he spoke. A widespread revival was most clearly seen during his second journey (1739-1741). As he toured the colonies, he would daily preach to large crowds in the open air; the crowds were too large for the churches.

Pictured Below: A Portrait of George Whitefield

Ben Frankin and George Whitefield

Benjamin Franklin was fascinated with Whitefield's speaking ability and the effects his teaching had on the people. Though Franklin never openly became a Christian himself, he did become a friend of Whitefield's and his publisher in America. He was impressed with the change Whitefield's gospel preaching brought on society. Franklin wrote that It was wonderful to see the change soon made in the manners of our inhabitants. From being thoughtless or indifferent about religion, it seemed as if all the world were growing religious so that one could not walk through the town in an evening without hearing psalms sung in different families of every street.

The faith and prayers of the righteous leaders were the foundation of the Great Awakening. Before a meeting, George Whitefield would spend hours--and sometimes all night--bathing an event in prayers. Fervent church members kept the fires of revival going through their genuine petitions for God's intervention in the lives of their communities.

While Edwards was the most prominent theologian of the time, by far the most influential and famous evangelist of the Great Awakening was George Whitefield. He was born in England and educated at Oxford, where he met and became friends with John and Charles Wesley. During his spare time at college, he visited the poor and those in prison. On June 20, 1736, at the age of twenty-two, he became an ordained minister. God blessed him with an amazing ministry, and wherever he spoke revival accompanied him. At the Wesley brothers' request, he joined them in Georgia to continue his ministry. After a few months, he returned to England and again reached thousands through his preaching. He became well-known in both the Colonies and Great Britain. His preaching spread revival and a new birth to the hearts of those who listened.

Unfortunately, many ministers became jealous of his God-given ability. In Bristol, the churches refused to allow him the use of their buildings. Undeterred, Whitefield preached outside On more than on occasion he addressed 30,000 people. He spoke persuasively with a loud, commanding, and pleasant voice. With weighty emotion and dramatic power Whitefield presented the gospel message to the masses, spreading the light of Christ with vigor and enthusiasm. He also united the independent movements of the Great Awaking and bound the separate colonies into a unit. Breaking through denominational boundaries he once said, "Father Abraham, who have you in heaven? Any Episcopalians? No! Any Presbyterians? No! Any Independents or Methodist? No, no, no! Whom have you there, then Father Abraham? We don't know those names here! All who are here are Christians--believers in Christ, men who have overcome by the blood of the Lamb and the word of his testimony. Oh, is that the case? Then God help me, God help us all, to forget having names and to become Christians in deed and in truth!" During his life, he made seven tours of the colonies and preached 18,000 sermons! There was hardly a portion of the colonies that did not feel his influence and love.

Old Lights vs. New Lights

Not everyone welcomed the beliefs of the Great Awakening. One of the principal opinions of the opponents was Charles Chauncy, a minister in Boston. Chauncy was especially critical of Whitefield’s preaching and instead supported a more traditional, formal style of religion.

By about 1742, a debate over the Great Awakening had divided the New England ministry and many colonists into two factions.

Preachers and followers who embraced the new ideas brought forth by the Great Awakening became distinguished as “new lights.” Those who affirmed the old-fashioned, traditional church ways were designated “old lights.”

Effects and Results of the Great Awakening

The Great Awakening in America in the 1730s and 1740s had tremendous results. The number of people in the church multiplied, and the lives of the converted manifested true Christian piety. Denominational barriers broke down as Christians of all persuasions worked together in the cause of the gospel. There was a renewed concern with missions, and work among the Indians increased. As more young men prepared for service as Christian ministers, a concern for higher education grew. Princeton, Rutgers, Brown, and Dartmouth universities were all established as a direct result of the Great Awakening. Some have even seen a connection between the Great Awakening and the American Revolution --Christians enjoying spiritual liberty in Christ would come to crave political liberty. The Great Awakening not only revived the American church but reinvigorated American society as well.

The significant working of God during the Great Awakening was far-reaching. Truly converted members now filled the pews. In New England, during the time from 1740 to 1742, memberships increased from 25,000 to 50,000. Hundreds of new churches were formed to accommodate the growth in church-goers. For the first time, the individual colonies had a commonality with the other colonies. They were joined under the banner of Christ. Clearly, their unity gave them strength to face the impending danger of war with England. Not only did the Great Awakening unite the colonies religiously but also politically. After being freed from inner sin, the colonists also sought freedom from external tyrants. The motto of the Revolutionary War was, "No King but King Jesus!"

|

A magazine just to report the revival |

Excerpts provided form Amy Puetz: The Great Awakening

Article Photo Credit: WikimediaCommons

Sources

Great Awakening, History.com

First Great Awakening, Wikipedia.org

The Great Awakening, Khanacademy.org

.jpg)