Times were tight for Phillis Wheatley. Although frail and asthmatic, she still had to earn money to support her family. Ever since she had been granted her freedom, she had scrabbled to make a living. She hoped that her standing as the first published African-American poet would help her. On this day, October 30, 1779, her notice appeared in the Evening Post and General Advisor of Boston. At that time, much publication was done by "subscription," meaning one had to get enough orders for a volume in order that the publisher could cover his costs.

Phillis projected a volume of poems and letters on various subjects "dedicated to the Right Hon. Benjamin Franklin, Esq: One of the Ambassadors of the United States at the Court of France."

At seven or eight years of age, in 1761, Phillis had been captured in Senegal, Africa and sold as a slave to the Wheatleys, a Boston family who showed kindness to her. She quickly mastered English. At twelve she was reading Greek and Latin. The Bible and the poetry of John Milton, Thomas Gray and Alexander Pope made a strong impression on her. She wrote her first poem at thirteen.

Phillis came to world attention when she authored a tribute to George Whitefield. She sent this to Whitefield's sponsor, Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntington. Like most of her poetry, it was deeply religious in tone:

Hail, happy saint, on thine immortal throne,

Possessed of glory, life, and bliss unknown;

The countess invited Phillis to England and helped her secure publication of her poems. This was the first book by an African American published. Immediately those who sought to abolish slavery held it up as proof that Africans were not inferior to other humans.

Because Phillis had been well-treated and had become a Christian she could say:

'Twas mercy brought me from my pagan land,

Taught my benighted soul to understand

That there's a God, that there's a Savior too:

Once I redemption neither sought nor knew...

The Wheatleys eventually offered her her freedom and she accepted, although she tended them until their deaths. When she struck out on her own, she entered a marriage that proved difficult. Her three children died young while she struggled to support them as a seamstress and poet. Poverty took its toll and New England's cold worsened her breathing problems.

Her hopes of raising enough subscriptions to print the book and earn a little extra money for food failed. She died in 1784, just thirty-one years old. Her poems were not earth-shaking. Thomas Jefferson sneered at them as "below the dignity of criticism." But her work has survived and she left a legacy as an individual who overcame serious drawbacks to leave a lasting name. African Americans can point back to her with pride, although many consider her a traitor to their race because she found some good in the circumstance of her enslavement.

Bibliography:

- Gates, Henry Louis, jr. The Trials of Phillis Wheatley. Basic Civitas Books, 2003.

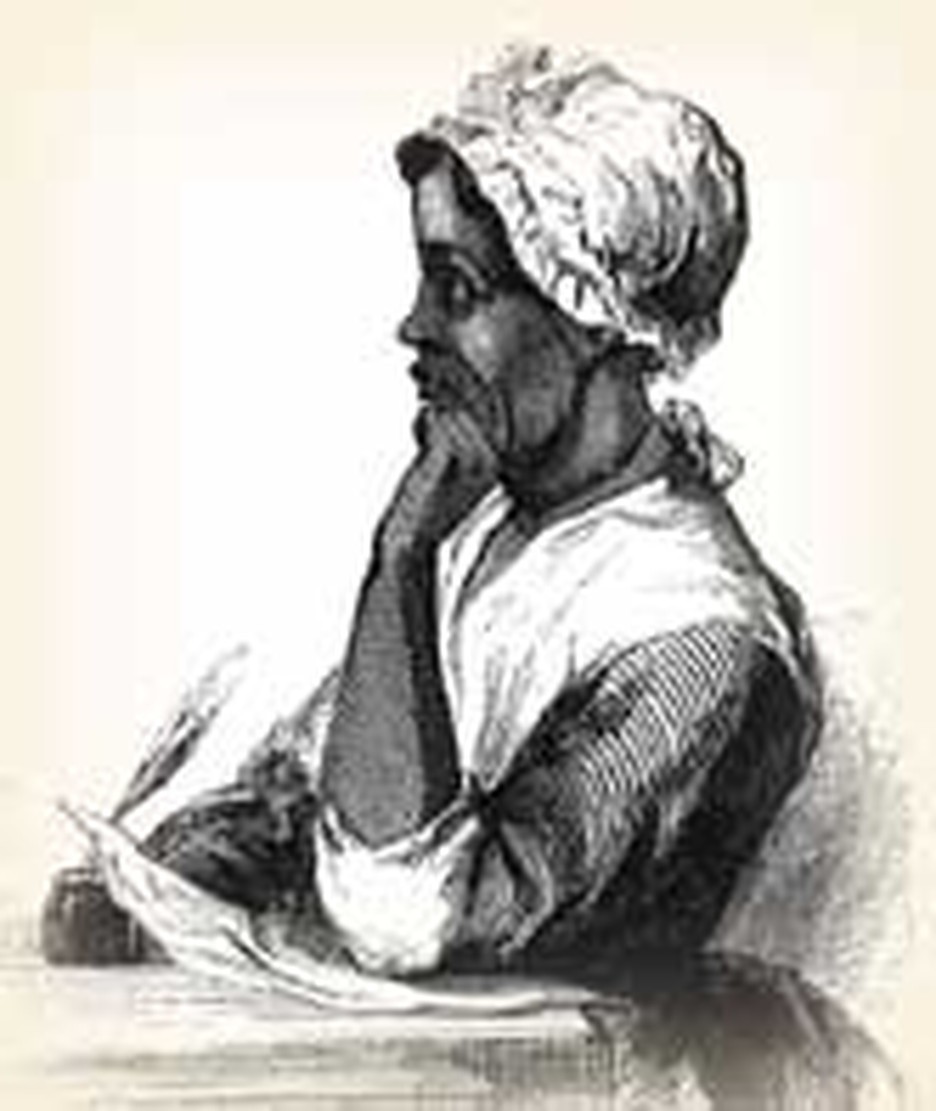

- Lossing, Benson J. Eminent Americans. New York: Mason Bros., 1857, source of the portrait.

- "Phillis Wheatley, Poet; A Brief Biography" https://www.jmu.edu/madison/wheatley/biography.htm

- "Phillis Wheatley, America's First Black Woman Poet: https://earlyamerica.com/review/winter96/ wheatley.html

- "Phillis Wheatley: Precursor of American Abolitionism" (https://www.forerunner.com/forerunner /X0214_Phillis_Wheatley.html)

- Robinson, William H. Phillis Wheatley in the Black American Beginnings. Detroit, Mi: Broadside Press

Last updated June, 2007.

.jpg)