England, at the beginning of the eighteenth century, was in a moral quagmire and a spiritual cesspool. Thomas Carlyle described the country's condition as "Stomach well alive, soul extinct." Deism was rampant, and a bland, philosophical morality was standard fare in the churches. Sir William Blackstone visited the church of every major clergyman in London, but "did not hear a single discourse which had more Christianity in it than the writings of Cicero." In most sermons he heard, it would have been impossible to tell just from listening whether the preacher was a follower of Confucius, Mohammed, or Christ!

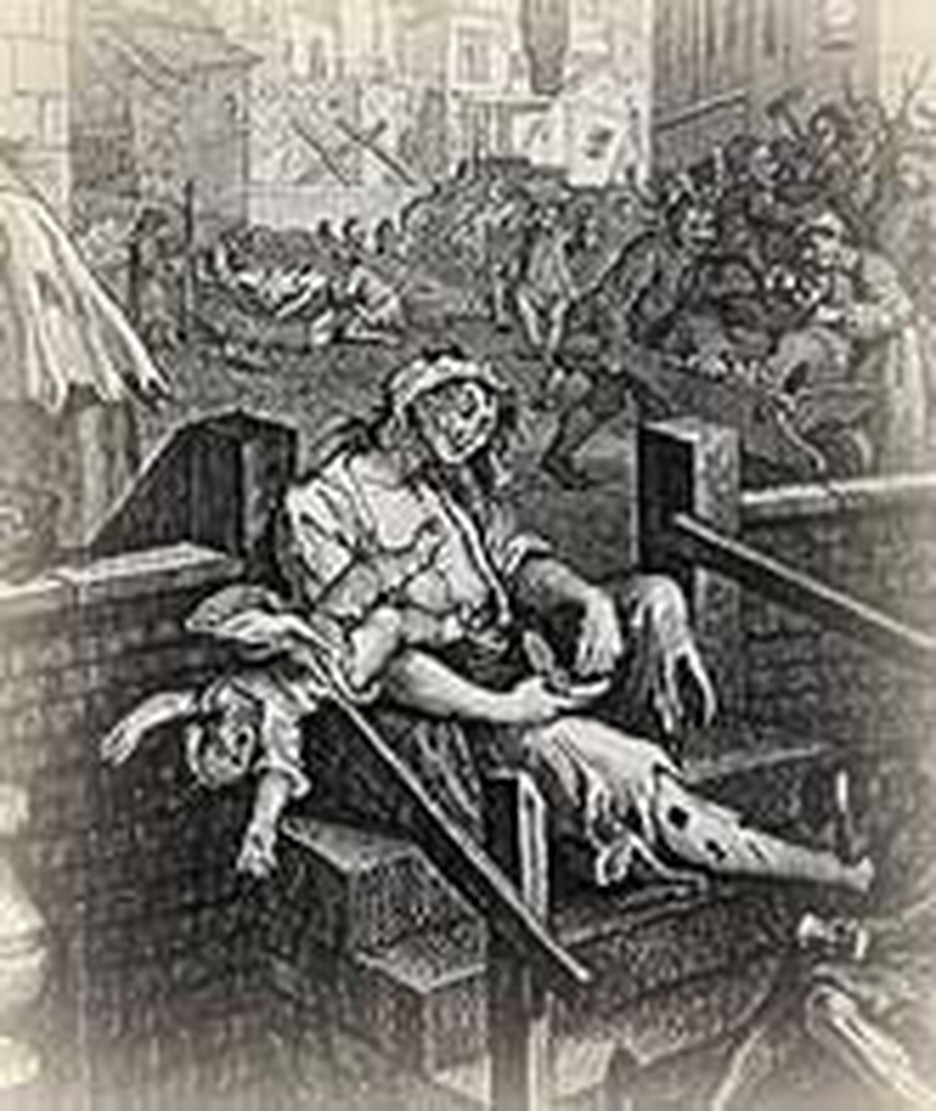

Morally, the country was becoming increasingly decadent. Drunkenness was rampant; gambling was so extensive that one historian described England as "one vast casino." Newborns were exposed in the streets; 97% of the infant poor in the workhouses died as children. Bear baiting and cock fighting were accepted sports, and tickets were sold to public executions as to a theater. The slave trade brought material gain to many while further degrading their souls. Bishop Berkeley wrote that morality and religion in Britain had collapsed "to a degree that was never known in any Christian country."

To the highways and byways

About the same time, George Whitefield, an ordained Anglican clergyman,

was converted and in 1737 began preaching in London and Bristol. In order

to reach the many non-church-goers, Whitefield spoke in the open fields,

and large crowds began gathering to hear the message of salvation. Whitefield

became an itinerant preacher, or "one of God's runabouts," as

he called himself, traveling extensively in his wide-ranging ministry.

In his day, itinerant preachers were often criticized as interfering with

or undermining the role of the parish priest. Whitefield countered that

many of the established clergy could not bring life to their people since

they themselves were spiritually dead.

One such spiritually dead clergyman was John Wesley, who later became the founder of Methodism (although he never intended to form a separate church). Wesley had gone to Georgia with James Oglethorpe to work as a missionary to the Indians. He soon returned to England in despair and wrote, "I went to America to convert the Indians; but O who will convert me!" On the ship going to Georgia, Wesley had met some Moravian immigrants and was impressed by their spiritual strength and joy in the Lord. Back in England, as Wesley struggled with his own sinfulness and need of salvation, he received spiritual counsel from the Moravian Peter Boehler. On May 24, 1738, during a meeting at Aldersgate, Wesley experienced God's saving grace and wrote, "I felt my heart strangely warmed. I felt I did trust in Christ, Christ alone for salvation; and an assurance was given to me that he had taken away my sins."

From George Whitefield, Wesley learned the importance of preaching in the open air to reach the masses. At first he could not imagine souls being saved unless they were in Church, but Jesus' "open-air preaching" of the Sermon on the Mount convinced him it was okay.

To the poor and discouraged

Wesley was not welcomed in many of the Church of England churches. He

was looked down upon as one of the contemptible religious "enthusiasts."

Maybe this was a blessing in disguise, as it permitted him to minister

to the poor in prisons, hospitals, workhouses, and at the mine pit heads.

Excessive taunts, verbal abuse, and even occasional physical violence

could not deter Wesley.

Wesley traveled over 250,000 miles in the cause of the gospel. In his preaching he talked continually of Christ and emphasized repentance, faith, and holiness. He said that repentance was like the porch of religion; conviction of sin always came before faith. Faith was the door of religion. Faith was "not only to believe that the Holy Scriptures and the articles of our faith are true, but also to have a sure trust and confidence to be saved from everlasting damnation through Christ." Holiness was religion itself, "the loving God with all our heart, and our neighbors as ourselves, and in that love abstaining from all evil, and doing all possible good to all men." As Wesley preached, multitudes responded. He noted in his journal that "the Word of God ran as fire among the stubble; it was glorified more and more; multitudes crying out, 'What must I do to be saved?' and afterwards witnessing, 'By grace we are saved through faith.'"

Wesley supervised the education of lay preachers to educate the people in small cell groups where discipline and faithfulness were learned. These preachers also distributed and sold Christian books to the people, helping provide them with spiritual food. Wesley pioneered the monthly magazine and edited Christian Living, a selection of theological and devotional literature for the lay person. He also was the first to print and use religious tracts extensively.

The effects spread

Wesley used all the profits from his literary works for charitable purposes,

and he encouraged Christians to become active in social reform. He himself

spoke out strongly against the slave trade and encouraged William Wilberforce

in his antislavery crusade. Numerous agencies promoting Christian work

arose as a result of the eighteenth century revival in England. Antislavery

societies, prison reform groups, and relief agencies for the poor were

started. Numerous missionary societies were formed; the Religious Tract

Society was organized; and the British Foreign Bible Society was established.

Hospitals and schools multiplied.

The revival cut across denominational lines and touched every class of society. England itself was transformed by the revival. In 1928 Archbishop Davidson wrote that "Wesley practically changed the outlook and even the character of the English nation."

Did Wesley save England from a revolution? |