Why was George Whitefield Controversial?

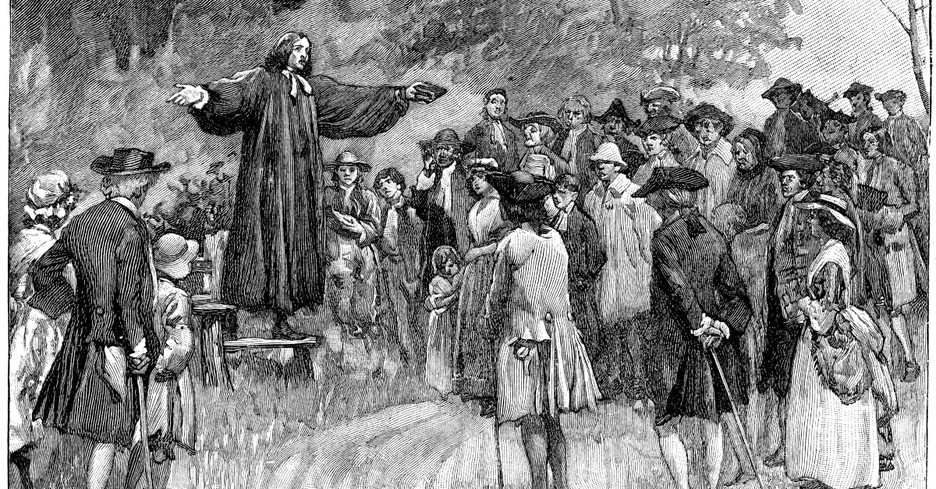

Because George Whitefield refused to soft-pedal his preaching, he received various responses. His bluntness sometimes offended people, and many established ministers of his time refused to allow him to speak in their pulpits. While angry listeners occasionally pelted him with everything from rotten fruit to dead cats, many people loved to hear him preach. He delighted the masses with his colorful style, often running around the stage and using dramatic facial and hand gestures. If some people were upset by this, so be it.

Early eighteenth-century crowds came to hear George Whitefield by the tens of thousands. When this traveling minister came to town, his meetings were not to be missed. In Philadelphia, a crowd cheered and yelled for George as he stood on a hill outside the central part of the city, mesmerizing the audience with his dynamic message.

"Father Abraham, whom have you in heaven?" he shouted. "Any Episcopalians?"

"No!" the people roared.

"Any Presbyterians?" Whitefield danced around the stage as he spoke, jabbing at the air with his hands.

"No!"

"Any Independents or Seceders. New Sides or Old Sides, any Methodists?"

"No! No! No!" the crowd shouted in reply.

He called out, "Whom have you there, then, Father Abraham? We don't know those names here! All who are here are Christians-- believers in Christ, men who have overcome by the blood of the Lamb and the word of his testimony . . . God help me, God help us all, to forget having names and to become Christians in deed and in truth."

IMAGE BELOW: Painting of George Whitefield Preaching

Whitefield and The Great Awakening

George Whitefield was born in 1714 in Gloucester, England. His father died when George was just two years old, leaving his mother to keep their inn running and support her family as best as she could. Whitefield considered becoming a preacher and spent hours studying his Bible as a young man, often reading late into the night. Shortly before entering Oxford, he was converted to faith in Christ. While at Oxford, he met John and Charles Wesley, forming a friendship that God would use on both sides of the Atlantic to influence multitudes with the Gospel.

All three Englishmen came to America in the 1730s. The movement known as the Great Awakening was just beginning, and this was a time when God's Spirit moved across the emerging nation, drawing people to himself. When Europeans first came to the New World in the early 1600s, some were eager to share their vital faith in Christ with the Native Americans. They desired to create a shining city on a hill that would be an example to the rest of the fallen world, an idea that John Winthrop preached about on his way to Massachusetts.

Many who came to the New World were seeking a country where they could freely practice their faith, unlike the nations from which they fled. But by the early 1700s, traditional churches had largely settled into self-satisfaction. Their preachers delivered dry sermons and avoided speaking about winning souls to Christ. Under this kind of leadership, faith often withered, lacking the vital spark that would make it relevant to their everyday lives.

No Lukewarm Christianity

George Whitefield detested lukewarm Christianity. To him, it was worse than no faith at all. In his ministry, he made every effort to shake churchgoers out of their apathy. He reminded them of Christ's words to the church at Laodicea in Revelation 3:16, where Christ said he would spew such congregations out of his mouth. The only kind of faith that pleased God was fervent, heartfelt belief, and Whitefield preached dramatically about this type of faith.

Because of his shouting and gyrations, pulpits closed to Whitefield in many "respectable" English churches. When this happened, he took his messages outside, often preaching in meadows at the edges of cities. This was considered nothing less than sacrilege to the "proper" church folks of his day.

When he came to America in the late 1730s, the colonies welcomed him, although some of the more traditional among the clergy were still bothered by his style of preaching. George and several other zealous ministers like Jonathan Edwards, Gilbert Tennent, David Brainerd, and the Wesley brothers rekindled believers' faith in Christ. Many also believe that God used the Great Awakening to draw the American colonies into closer union, preparing them for independence from Britain. The Great Awakening revival was an event in which all the colonies shared, giving them a common, unifying experience.

George Whitefield, the Showman

Whitefield was a gifted orator who mesmerized audiences, using his voice in the manner of a skilled actor. He was a master storyteller, a skill he often used in his preaching. Once, when he described a storm at sea, his description was so vivid that a sailor in the audience actually cried out, "To the lifeboats! To the lifeboats!" George had endured many storms during his thirteen voyages across the Atlantic Ocean and drew on this experience to paint his vivid word pictures. Some people even fell to the floor as though dead, so strong were their feelings of conviction when they heard Whitefield's messages. At a time when there were no microphones, this powerful preacher projected his voice so that he could be heard up to a mile away.

An Important Friendship

George Whitefield's preaching allowed a young Philadelphia printer to perform an experiment. Benjamin Franklin joined the crowds that thronged to hear Whitefield preach, but rather than listening to his message, Ben turned and walked away. As he walked further away, he stopped periodically to see if he could still hear the British preacher. Franklin said, "Imagining then a semicircle, of which my distance should be the radius, and that it was filled with auditors to each of whom I allowed two square feet, I computed that he might be heard by more than thirty thousand. This reconciled me to the newspaper accounts of his having preached to twenty-five thousand in the fields."

Ben Franklin offered to print Whitefield's sermons so people could buy them, and he also housed the preacher above his shop on Market Street. When the Philadelphia clergy refused to allow Whitefield to speak in their churches, Franklin purchased a building so that all preachers could have a place to address the people. He also supported Whitefield's orphanage in the Georgia colony. Although the two men became devoted friends who respected each other deeply, Ben Franklin always resisted Whitefield's efforts to convert him. Through Whitefield's sermons and long conversations, however, he came to believe that God had a special place for America, that "we were a people chosen by God for a specific purpose."

One Last Sermon

Whitefield delivered over 18,000 sermons to ten million people during his lifetime, averaging roughly ten sermons a week. This was truly extraordinary at a time when there was no television or mass communication.

Late in September 1770, George fell ill after preaching to crowds in New England. On September 29, he prayed for strength to deliver one last sermon. At first, he was barely able to stand, but he rallied to preach on faith and works for two hours. Later that night, he had a severe asthma attack. Although a doctor was summoned, George Whitefield died at 6 o'clock the following morning.

Below is George Whitefield's grave in the crypt of Old South Presbyterian Church, Newburyport, Massachusetts.

Reactions to Whitefield's Controversial Preaching

Opposition to George Whitefield and other preachers of the Great Awakening sometimes revolved around their appeal to the lower social classes and to women. One of Whitefield's greatest supporters in England, Lady Huntington, sponsored his new preaching style. She established over 60 chapels to encourage this new style and urged her friends and those in her social circles to hear Whitefield preach. The Duchess of Buckingham took offense and wrote to Lady Huntingdon: "I thank your Ladyship for the information concerning these preachers. Their doctrines are most repulsive and strongly tinctured with impertinence and disrespect toward their superiors in that they are perpetually endeavoring to level all ranks and do away with all distinctions. It is monstrous to be told that you have a heart as sinful as the common lechers that crawl on the earth. This is highly offensive and insulting and I cannot but wonder that your Ladyship should relish any sentiment so much at variance with high rank and good breeding."

Undeterred, Lady Huntington invited men of great stature to her home to hear Whitefield preach. Among those invited to her house were Lord Bolingbroke, Lord Chesterfield, Horace Walpole, and David Hume. In order to protect Anglican bishops from possible embarrassment, she established a curtained alcove for them to guard their privacy and dubbed it the Nicodemus Corner. So great was her zeal for the Lord and His ministers that when Oxford expelled several students for holding Methodist meetings in the new preaching style, she launched a new, non-denominational seminary.

An Eyewitness Account

Now it pleased God to send Mr. Whitefield into this land; and hearing of his preaching at Philadelphia, like one of the Old apostles, and thousands flocking to hear him preach, and great numbers were converted to Christ; I felt the Spirit of God drawing me by conviction.

Then one morning there came a messenger and said Mr. Whitefield [was] to preach this morning. I was in my field at Work. I dropt my tool that I had in my hand and ran to my pasture for my horse with all my might fearing that I should be too late to hear him. I brought my horse home and soon mounted and took my wife up and went as fast as I thought the horse could bear, and when my horse began to be out of breath, I would get down and put my wife on the Saddle and bid her ride as fast as she could and not Stop or Slack for me except I bad[e] her, and so I would run until I was much out of breath, and then mount my horse again, and we [went] along as if we were fleeing for our lives, all the while fearing we should be too late, for we had twelve miles to ride double in little more than an hour.

And when we came within about half a mile of the road; I heard a noise something like a low rumbling thunder and presently found it was the noise of horses coming down the road. A Cloud of dust arose some Rods into the air over the tops of the hills and trees. I heard no man speak a word but every one pressing forward in great haste. 3 or 4,000 people assembled together. I turned and looked towards the great river and saw the ferry boats bringing over loads of people; the land and banks over the river looked black with people and horses all along the 12 miles. I saw no man at work in his field, but all seemed to be gone.

When I saw Mr. Whitefield come upon the Scaffold he looked almost angelical, a young, slim slender youth before some thousands of people with a bold undaunted countenance, and he looked as if he was Cloathed with authority from the Great God. And my hearing him preach gave me a heart wound; by God's blessing my old foundation was broken up, and I saw that my righteousness would not save me.

Excerpted from George Leon Walker, Some Aspects of the Religious Life of New England (New York: Silver, Burnett, and Company, 1897), 89-92.