Creation of the King James Bible

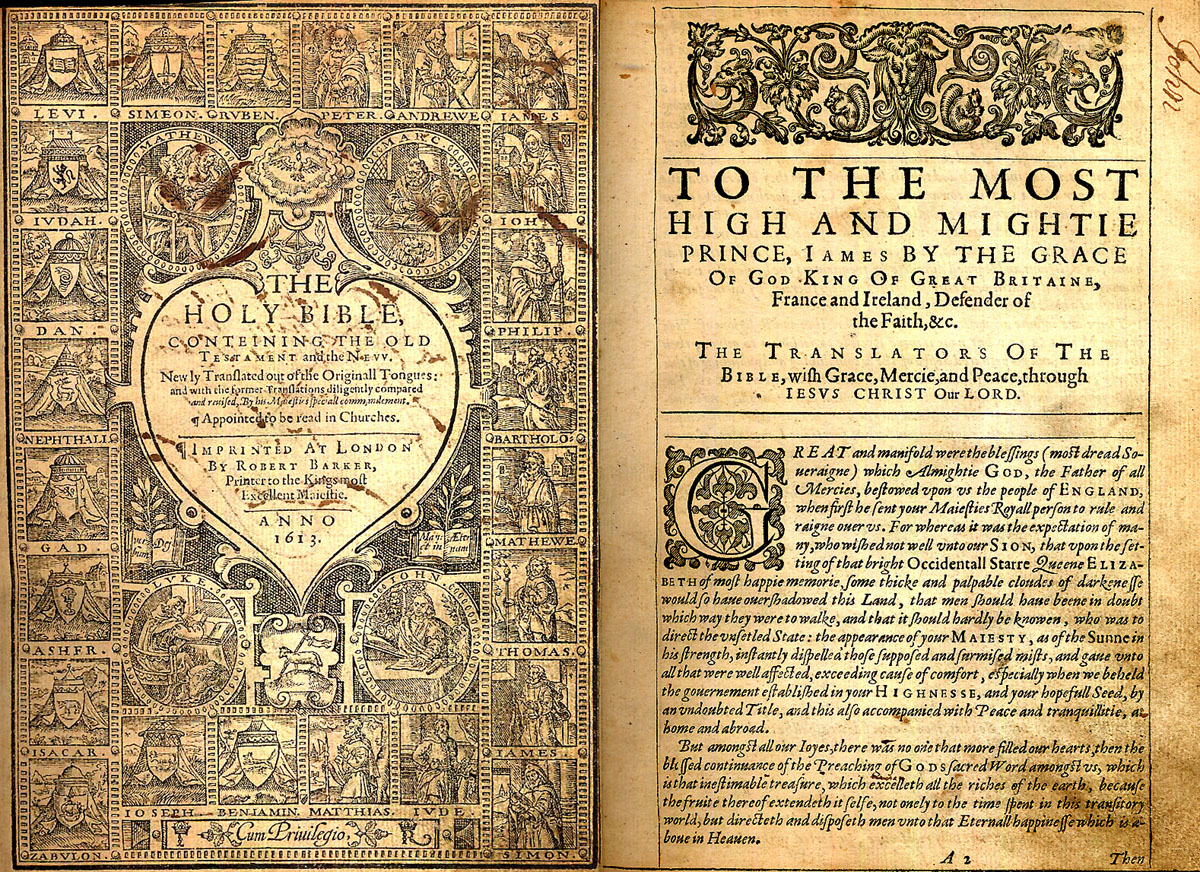

The commissioning of the King James Bible took place in 1604 at the Hampton Court Conference outside of London. The first edition appeared in 1611. The King James version remains one of the most significant landmarks in the English tongue. It has decidedly affected our language and thought categories, and although produced in England for English churches, it played a unique role in the historical development of America. Even today, many consider the King James Bible the ultimate translation in English and will allow none other for use in church or personal devotions. However, the story behind the creation of this Bible translation is little known and reveals a fantastic interplay of faith and politics, church and state. To understand what happened, we need to go back to the world of the early 17th century.

Imagine what it was like to live in England in 1604. Theirs was not a world like ours where speed, change, and innovation are consciously cultivated and thoughtlessly celebrated. Their world moved much slower, and continuity was prized over change. In their world, the crowning of a new monarch was a grand event that profoundly affected the life and identity of the nation. The monarch would rule for life. There was no continuous cycle of election campaigns in their world as there is in ours.

The Puritans Miscalculate

Consider the mood that must have prevailed at Queen Elizabeth's death. Her rule had provided a great sense of security and stability for her country.

The Puritans were eager to continue the Reformation's work, and Elizabeth's death seemed their opportune moment. Scotland's James VI succeeded her, thus becoming James I of England. Because James had been raised under Presbyterian influences, the Puritans had reason to expect James to champion their cause. They were gravely mistaken.

James was acquainted with many of their kind in Scotland and did not like them. However, they were a sizeable minority, serious, well-educated, highly motivated, and convinced of the righteousness of their convictions. Regardless of personal antipathy, James did not consider it politically wise to ignore them.

James wanted unity and stability in the church and state but was well aware that the diversity of his constituents had to be considered. The Papists (as they were called then) longed for the English church to return to the Roman fold. There were also the Puritans, loyal to the crown but wanting even more distance from Rome. They insisted that England's Reformation did not go far enough because it still retained too many Catholic elements. They had no trouble agreeing with John Knox's description of Elizabeth as "neither good Protestant nor yet resolute papist."

The Presbyterians wanted to do away with the hierarchical structure of powerful bishops. They advanced what they believed was the New Testament model of church administration under elders or presbyters.

The Nonconformists and Separatists, some of whom would later become America's Pilgrims, wanted the state out of church affairs altogether. They were not seen as a potent force then, but their movement slowly developed.

Then there was Parliament -- eager to expand its power beyond its role at the time. There was a significant Puritan influence and representation in the Parliament.

To keep our alliteration, let’s refer to the next group as the "Prayer Book" establishment or the Bishops and the hierarchy of the English church. They were a genuine elite, holding exceptional power, privilege, and wealth. To them, Puritan agitation was far more than an intellectual abstraction to be debated at Oxford and Cambridge. If the Puritans were to prevail, this hierarchy had much to lose.

James Comes to the Throne

As James prepared to take the throne, strong stirrings of discontent caused him grave concern. Elizabeth died on March 24, 1603, after ruling for 45 years. James received word of his cousin Elizabeth's death and his appointment to the throne, and on April 5, he began his journey from Edinburgh to London for his coronation.

James' journey south was marked by a critical interruption. A delegation of Puritans presented James with a petition outlining their grievances and the desired reforms. The document was known as the Millenary Petition and had over 1,000 clergy signatures, representing about ten percent of England's clergy. This petition was the catalyst for the Hampton Court Conference. From the beginning, the petition sought to allay suspicions regarding loyalty to the crown. It treated four areas: church service, church ministers, church living and maintenance, and church discipline. It also set forth objections that perhaps sound rather frivolous to us today, but were serious matters to the Puritans. Among the things they objected to were the use of the wedding ring, the sign of the cross, and the wearing of specific liturgical clothing. However, the Millenary Petition contains no mention at all of a new Bible translation.

James took the petition seriously enough to call for a conference. In a royal proclamation in October 1603, the king announced a meeting to take place at the Hampton Court Palace, a luxurious 1,000-room estate just outside of London, built by Cardinal Wolsey.

The Council Participants

The participants in the conference were the king, his Privy Council of advisors, nine bishops and deans. There were also four moderate representatives of the Puritan cause, the most prominent being Dr. John Reynolds, head of Corpus Christi College. Clearly, the deck was stacked against the Puritans, but at least they were given a voice.

King James Sets the Tone

Like Constantine at the opening of the Council of Nicea, James delivered the opening address. He immediately set the tone and gave clear cues of what to expect. The doctrine and polity of the state church were not up for evaluation and reconsideration.

James immediately proceeded to hint that he found a great deal of security in the structure and hierarchy of the English church, in contrast to the Presbyterian model he witnessed in Scotland. He made no effort to hide his previous frustration in Scotland.

The Puritans were not allowed to attend the first day of the conference. The four Puritans were allowed to join the meeting on the second day. John Reynolds took the lead on their behalf and raised the question of church government. However, any chance of his being heard was lost by one inopportune and, no doubt, unintended reference.

He asked if a more collegial approach to church administration might be in order. In other words, "Let's broaden the decision-making base." Reynolds posed his question this way: "Why shouldn't the bishops govern jointly with a presbytery of their brethren, the pastors, and ministers of the Church."

The word presbyterie was like waving a red flag before a bull. The king exploded in reply: "If you aim at a Scots Presbyterie, it agreeth as well with monarchy as God and the devil! Then Jack, and Tom, and Will, and Dick shall meet and censure me and my council." He then uttered what can be considered his defining motto and summary: "No bishop, no King!"

At this point, he warned Reynolds: "If this be all your party hath to say, I will make them conform themselves, or else I will harrie them out of the land, or else do worse!"

While Reynolds' unfortunate use of the term presbytery damaged the Puritan case, he does get credit for proposing the most significant achievement of the conference. Reynolds "moved his majesty that there might be a new translation of the Bible because those which were allowed in the reign of King Henry VIII and King Edward VI were corrupt and not answerable to the truth of the original." James warmed to a new translation because he despised the then-popular Geneva Bible. He was bothered more by its sometimes borderline revolutionary marginal notes than by the actual quality of the translation.

A New Translation of the Bible

So James ordered a new translation. It was to be accurate and true to the originals. He appointed fifty of the nation's finest language scholars and approved rules for carefully checking the results.

James also wanted a popular translation. He insisted that the translation use old familiar terms and names and be readable in the terminology of the day.

It was made clear that James wanted no biased notes affixed to the translation, as in the Geneva Bible. Rule #6 stated: "No Marginal Notes at all to be affixed, but only for the explanation of the Hebrew or Greek Words." Also, James was looking for a single translation that the whole nation could rely on "To be read in the whole Church," as he phrased it.

He decreed that special pains be "taken for a uniform translation, which should be done by the best learned men in both Universities, then reviewed by the Bishops, presented to the Privy Council, lastly ratified by the Royal authority...."

A Colossal Achievement

Consider how preposterous it was to have a team of elite scholars writing for a largely illiterate public. We can only stand back in amazement at their achievement. Think how ludicrous the translation mandate was. It called for a product commissioned to reinforce a clear-cut royal political agenda, to be done by elite scholarly committees, and reviewed by a self-serving bureaucracy, with ultimate approval reserved to an absolutist monarch. The final product was intended primarily for public and popular consumption. It was to be read orally -- intended more to be heard in public than to be read in private.

How many works of literary genius do you recall that were done by the committee? How many premier scholars are you aware of who can write for the ear? Not to mention in a context intended to evoke a spirit of worship!

How optimistic would you have been that a team of about 50 could handle the technical and linguistic challenges while at the same time producing work with a cadence, rhythm, imagery, and structure that would resonate so deeply with the popular consciousness that it uniquely shaped civilization and culture? However, history shows that they successfully created a translation that not only met the needs of their generation but also succeeded in influencing the lives of generations to come.