Solomon Stoddard had a dilemma on his hands. New England Puritans held to a Covenant Theology. In its simplest terms this said that any group of people who pledged to each other to obey God's word for the good of all could form a congregation or church. Covenant members had to give a verbal testimony of their experience of grace. Stoddard's dilemma grew out of Covenant Theology.

Covenant members married and had children and grandchildren. What should be done with these newcomers? Had they experienced grace? Were they part of the church or not?

Richard Mather drafted a solution in 1662. It was called the Halfway Covenant. Under it, infants could be baptized, but the children of covenant members were not allowed to partake of the Lord's Supper until they made a confession of personal faith at the age of fourteen or so. Unless churchgoers made such a confession of faith, they should not partake of the bread and wine.

Solomon Stoddard, the Congregational minister at Northampton, Massachusetts, pointed out the dilemma in Mather's Halfway Covenant. Under it, no one was allowed to partake of the Lord's Supper until he had certain knowledge and assurance of salvation; without this knowledge, attendance at the sacrament was damning. However, under that same theology, no man could be absolutely sure he was eternally saved. The very thing you couldn't be sure of was the one thing the Halfway covenant required you to declare. But if no one could be absolutely sure he or she was eternally saved, how could anyone make a declaration of salvation in order to take the elements?

Stoddard's solution was to allow any well-behaved churchgoer who chose to do so to partake of the bread and wine even if he or she wasn't sure of salvation. Stoddard argued that if they were not saved, taking the bread and wine might help them secure saving grace or even convert them. On this day, November 5, 1677, he adopted this new practice.

Since Stoddard had a good deal of influence, his example was followed by most preachers in Western Massachusetts. Ironically, one who did not follow him was his own grandson, Jonathan Edwards. This brilliant thinker, who succeeded his grandfather as pastor of Northampton, was not persuaded that open communion should be allowed. He charged that the Puritans had drifted into a religion of works. Seeking to restore a purer Calvinism, he rejected Stoddard's principle. In 1750, his congregation booted him out of the pulpit.

Bibliography:

- Coffman, Ralph J. Solomon Stoddard. Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1978.

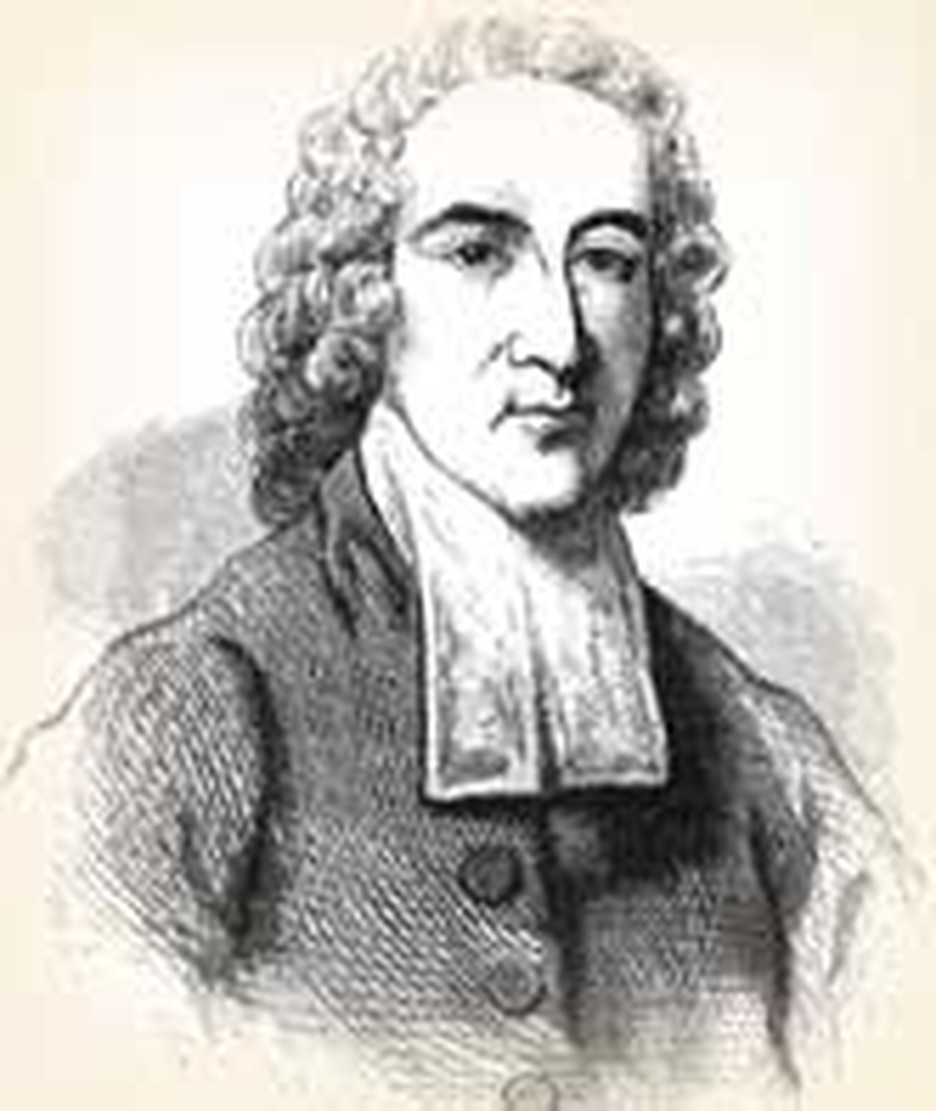

- Lossing, Benson J. Eminent Americans. New York: Mason Bros., 1857. Source of the portrait.

- Stoddard, Solomon. The defects of preachers reproved: in a sermon preached at Northampton, May 19th, 1723. Boston: 1747.

- "Stoddard, Solomon." Dictionary of American Biography. New York: Scribner, 1958 - 1964.

- Various encyclopedia and internet articles.

Last updated April, 2007.