Oh, my Lord!

Oh, my good Lord!

Keep me from sinkin' down.

I tell you what I mean to do

(Keep me from sinkin' down)

I mean to go to heaven too

(Keep me from sinkin' down)

I look up yonder and what do I see?

(Keep me from sinkin' down)

I see the angels beckonin' me

(Keep me from sinkin' down)

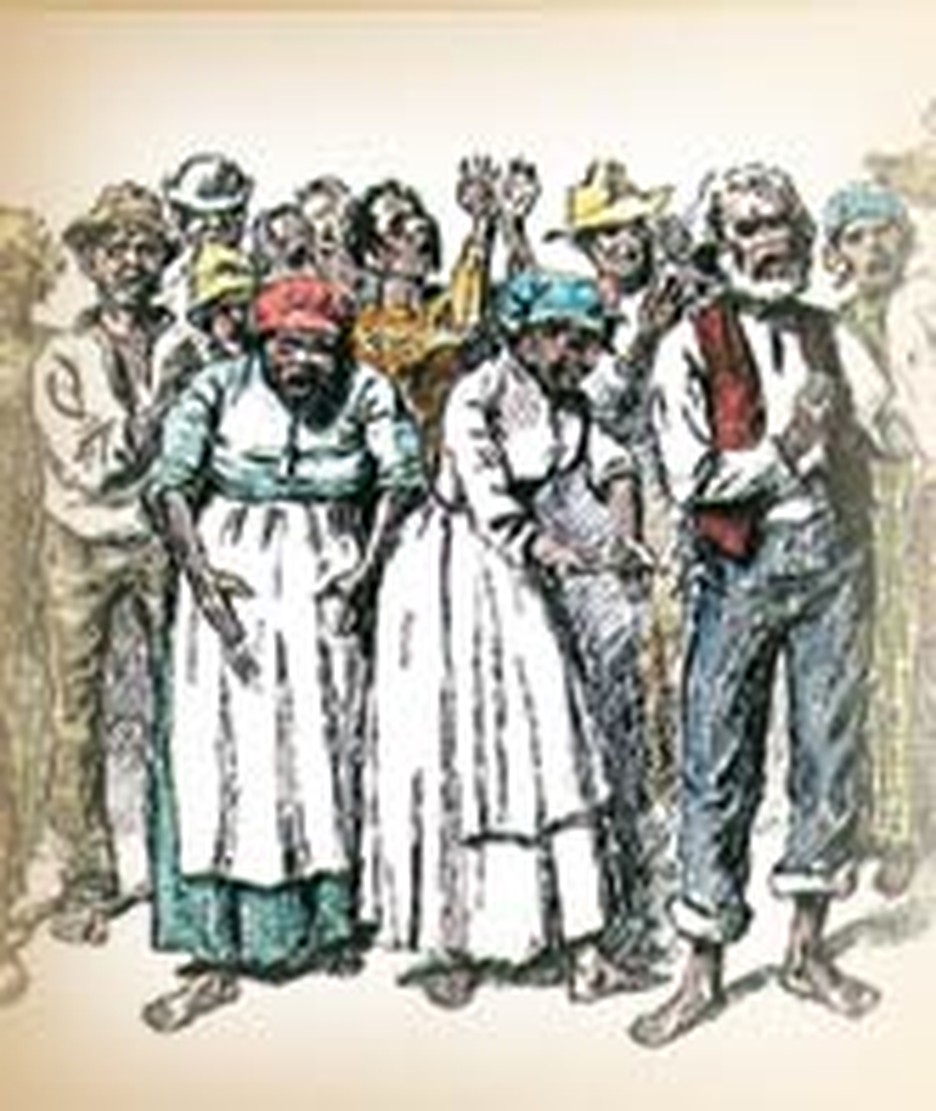

"As we wheeled up the avenue, our numbers ever increasing, the Negroes broke into another song, more joyful than the last, and all clapped hands in unison, when they sang the chorus until the air quivered with melody." (From an account by Mary Livermore, a Boston school teacher in Virginia before the Civil War.)

Slave Song Spirituals

Singly or by twos the black slaves slipped into the torch-lit forest grove. What they were doing was illegal. They could be whipped for it. But they had to sing, had to sing without restraint, had to pour out to God their souls' deepest prayers, longings and complaints, regardless of consequences. With bodies swaying and eyes half-closed, they sang, lifting to heaven their anguish and triumph.

Oh, bye an' bye, bye an' bye

I'm goin' to lay down my heavy load...

I'm troubled, I'm troubled,

I'm troubled in mind

If Jesus don't help me

I surely will die. . .

Simple the words may have been, but they expressed spiritual aspirations and sorrows as deep as any found in Christendom. What is more, they were expressed with rhythms of utmost sophistication and melodies plaintive, haunting, or oddly original.

The blacks who stepped in chains from the slave ships were a musical people, used to expressing religious ideas in song. Sold into hard work, poverty and oppression in America, they turned to songs for solace, singing on every possible occasion in rhythms that had been long familiar to their race. They sang while picking cotton or shucking corn, sang on the chain gang, sang in prison, sang in church-when allowed to attend.

If the slaves had to judge Christianity only by their white masters, few might have become Christians. They were well aware of the shortcomings of their owners, whose faith was often merely a Sunday profession, ignored during the harsh week. Hypocrisy found pointed comment in Spirituals.

Everybody talkin' about

Heaven ain't goin' there...

But just as the gospel had appealed in the first century to the poor and to slaves, so it appealed to Africans similarly situated. The sufferings of Christ and of the ancient Jews drew black folk to Christianity. Moses delivering his people from Egyptian bondage, Joseph sold as a slave by his own brothers, Daniel flung by a tyrant into a lion's den--these timeless stories were the agents that evoked a response of faith from the slave community, faith which found utterance in song.

Go down Moses,

'Way down in Egypt land

Tell ol' Pharaoh

To let my people go.

Little wonder, then, that of all the slave songs, it is the Spirituals, expressing the deepest religious emotions of souls touched by Christ, which kindles a flame in our hearts. Spirituals are recognized as some of the world's most authentic spiritual utterances since David penned the Psalms.

Identity Found in Spirituals

These Spirituals gave the slaves an identity which appearances seemed to belie: that of a people chosen by the Lord. Just as the Lord fought for Moses and the Israelites, just as he toppled Goliath before David, just as he appeared to Jacob on the ladder, so would he work in their lives. And if they were not delivered while yet living in this world, there remained freedom in the heavenly Canaan. Their songs summarized these beliefs, expressing in broken words the genuine spiritual realities of a world unseen, the world of Christian virtues: forgiveness, hope, faith, love, endurance, eternal life, holiness. James Weldon Johnson noted this and commented, "The Negro took complete refuge in Christianity, and the Spirituals were literally forged of sorrow in the heat of religious fervor. They exhibited, moreover, a reversion to the simple principles of primitive, communal Christianity." No wonder blacks, however weary after a hard day's work, risked the sometimes cruel anger of masters to steal into the woods at night and improvise music for hours.

The whole group could participate; repetitive choruses and antiphonal responses between leader and people characterized Spirituals. And while many of the songs were mournful, others were filled with the joy of Christ.

Oh, religion is a fortune,

I really do believe...

"Remarkably buoyant!"

Frederick Douglass, a prominent escaped slave, wrote of his captivity: "We were at times remarkably buoyant, singing hymns and making joyous exclamations, almost as triumphant in their tone as if we had already reached a land of freedom and safety."

The Jubilee Singers

The world at large first heard Spirituals in the 1870s, shortly after the Civil War emancipated America's blacks. The Fisk Jubilee Singers, a group of ex-slaves, toured the United States and Britain with orchestral renditions. Many listeners were amazed at the vitality of what they heard. Western music soon showed the influence. Spirituals, which had rescued faithful black Christians from "sinkin' down," now added vitality to the musical idioms of the world.

Slaves were auctioned off as if they were animals to be bought and sold. In some years over 70,000 black men, women and children were shipped to plantations in the West Indies and America.

Fascinating Facts About Slave Songs

- The ninth symphony of Antonin Dvorak, a favorite with many concert-goers, may employ Spiritual melodies. "Here in the music you have neglected, even despised, is something spontaneous, sincere, and different, native to your country," he said. "Why not use it?" He used similar melodies in his "American" quartet, opus 96.

- Theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer (1906-1945) studied in New York in the 1930s. A musician in his own right, he appreciated the Spirituals he heard at the Abyssinian Baptist Church and recorded some to play to his students in Germany.

- "Hymns more genuine than these have never been sung since the psalmists of Israel relieved their burdened hearts and expressed their exaltation. Nor will they die, because they spring like these from hearts on fire with a sense of the reality of spiritual truths." Edith A. Talbot

- Today's gospel music is directly descended from Spirituals. Renowned jazz musician Thomas A. Dorsey (not to be confused with the band leader Tommy Dorsey), a former blues man turned gospel song writer was an early promoter of the genre. Most famous of his gospel hymns is, "Precious Lord, Take My Hand" translated into more than 50 languages.

- The composers of Spirituals are unknown. They are a genuine folk music. Because the songs became an oral tradition, the words varied from region to region when song leaders found it necessary to ad-lib lines they had forgotten.

- Slaves were auctioned off as if they were animals to be bought and sold. In some years over 70,000 black men, women and children were shipped to plantations in the West Indies and America.

In their Own Words

| They crucified my Lord an' he never said a mumbalin' word; They crucified my Lord an' he never said a mumbalin' word; Not a word, not a word, not a word. He bowed his head an' died, an' he never said a mumbalin word; He bowed his head an' died, an' he never said a mumbalin word; Not a word, not a word, not a word. | You got a right, I got a right, We all got a right to the tree of life; Yes, you got a right, I got a right, We all got a right to the tree of life. The very time I thought I was los' The dungeon shook an' the chain fell off. You may hinder me here But you cannot there 'Cause God in his heaven Goin' to answer prayer. O Brethren, You got a right, I got a right We all got a right to the tree of life. | Can't you live humble? Praise King Jesus! Can't you live humble To the dyin' lamb? Lightenin' flashes, thunders roll, Make me think of my poor soul. Come here, Jesus, come here please See me Jesus on my knees. Can't you live humble? Praise King Jesus! Can't you live humble To the dyin' lamb? |

Many African-American spirituals found their way into our hymnals including:

•Let Us Break Bread Together

•Go Tell It on the Mountain,

•Lonesome Valley

•Amen

•Were You There?

•He's Got the Whole World in His Hands

•There is a Balm in Gilead

•Lord, I Want to Be a Christian

One of the Greatest Miracles (Editor's Notebook)

When in the fourth grade of grammar school, we were visited once a week by an itinerant and kindly music teacher named Luke Gaskell. He did his best to help us love and learn music. Mr. Gaskell's devoted efforts failed to uncover any musical talents in this particular student, but I remain indebted to him for the single class period he devoted entirely to teaching us the Negro spiritual "Steal Away, Steal Away to Jesus." This teacher took us through the song word by word, line by line, drawing forth the depths of simultaneous pain and exaltation. He made the experience of slavery real but he also helped us feel the joy of song that can give solace to and emancipate the spirit.

I cannot remember where I read it, but one historian commented somewhere that one of the greatest miracles and movements in all Christian history is the acceptance of the Gospel by so many African-Americans. The slaves not only appropriated the faith that was culturally identified with the oppressor, but gave it enriched meaning and depth, not least through their music and worship.

A friend read this issue before publication and said: "I had known nothing about the subject. Before I was done reading I found myself crying to God for unfaltering faith so that I might spend eternity with a people capable of such an outpouring of spiritual passion."

Christians still get clobbered with the old refrain that the New Testament supported slavery. What a distortion! The New Testament recognized slavery as a long-established fact of life. But consider the brilliance and beauty of Paul's demolishing the foundation of slavery by discrediting all discriminatory human divisions (Gal. 3:20) and in the book of Philemon establishing the full humanity and worth of runaway slave Onesimus in the most exalted terms. Interestingly, one of the criticisms the early church had to face was that it was populated by so many poor and slaves.