Scotland took seriously the religious reforms introduced in the sixteenth century by John Knox, which included church rule by elders. When King Charles I and Archbishop William Laud attempted to force Scotland to adopt the English prayer books and a form of church government controlled by bishops, the Scots balked. They were so fierce about it that the Bishop of Brechin felt he had to read from the new prayer book with a pair of pistols in his hands. The Scots determined not to give ground.

Several times before in the short history of the Scottish reformation, groups of Scots had covenanted together to hold some line or another. In 1638, they drew up the greatest of their covenants.

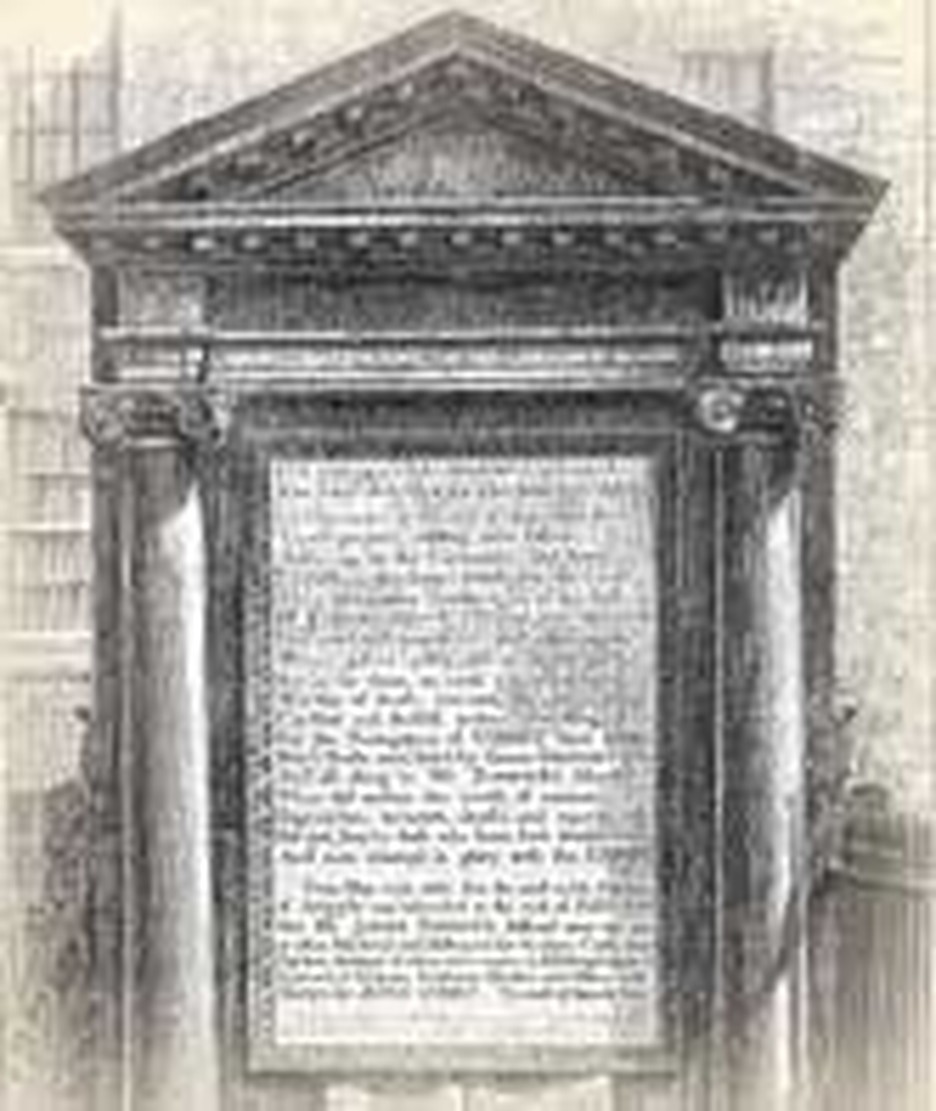

This National Covenant was not directly an act of rebellion, although it demanded changes in the political arrangement. Its authors, Archibald Johnston of Wariston and Alexander Henderson demanded that the Scottish Parliament and General Assembly be free from the King's interference. They called for the abolition of bishops, who were usually agents of the king. Although loyal to the king, the Scots would not let him tell them how they should pray. They said they would resist to the death any attempt by him to steal Christ's rights in the church.

The document contained an intriguing mixture of citations from the law and allusions to the Bible. It concluded by calling "...the LIVING GOD, THE SEARCHER OF OUR HEARTS" to be a witness..." God, they said, knew their sincere desire and that they weren't faking their determination. They knew they had to give an account to Jesus Christ in the judgment day, and said so. To break the covenant would be to come under God's everlasting wrath, and to lose the respect of the world. Therefore, they humbly pleaded with the Lord to strengthen them by his Holy Spirit, "and to bless our desires and proceedings with a happy success; that religion and righteousness may flourish in the land, to the glory of GOD, the honour of our King, and peace and comfort of us all."

On this day, Wednesday, February 28, 1638, the covenant was first read aloud in the Greyfriars Church of Edinburgh. This was the same church where John Knox had once been taken for trial. It was already dear to the Scots, and now would be more so. Leading individuals signed the covenant on the spot.

The next day, it was taken to Tailors Hall, where the burghers of the city added their names. In subsequent days and weeks, the movement gained force as copies made their way not only throughout Scotland, but into Ireland. Everywhere, people signed.

The Scots stood by their word, too. When the king would not listen to them, Civil War ensued. A few years later, Parliament adopted a similar document, known as the Solemn League and Covenant. A people bound to the covenant emerged who became known as Covenanters. Eventually they won many of the rights that they had claimed in their covenant.

Bibliography:

- "National Covenant." The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, edited by F. L. Cross and E. A. Livingstone. Oxford, 1997.

- Orr, Brian. "The National Covenant and Greyfriars Kirk." http://www.tartans.com/articles/cov9.html.

- Smellie, Alexander. Men of the Covenant; the story of the Scottish Church in the Years of Persecution. New York: Fleming H. Revell Company, 1903.

- Various encyclopedia and internet articles.

Last updated June, 2007.