On this day, July 11, 1656, the authorities in Boston, Massachusetts were dismayed. Aboard the Swallow, which had just sailed into harbor, were two Quaker women, the first Quakers to reach the colony. Massachusetts was a Puritan commonwealth. Its leaders believed that a Christian state had an obligation to regulate religious belief and behavior. Admitting believers from other denominations would eventually unbalance the arrangement between government and church. This was especially true of Quakers, who were notorious for acts of civil disobedience whenever their personal convictions conflicted with government policy. To most denominations of the day, the Quakers, with their rejection of traditional theology could be defined with one word: heretics.

Deputy Governor Richard Bellingham acted quickly. He confined Ann Austin and Mary Fisher to the ship and ordered the public executioner to burn all of the literature that they had brought with them. He knew the power of print to go where evangelists could not.

On second thought, it seemed better to Bellingham to place the women where the state, not a shipmaster, had control of them. So he brought them ashore: Ann, an old woman, the mother of five children; and Mary, a former serving maid, aged 33. Earlier that year she had been whipped in England for saying that it was wrong to make a vocation out of preaching.

In Boston, the two underwent a severe ordeal. They were examined by the magistrates and "found not only to be transgressors of the former laws, but to hold very dangerous, heretical, and blasphemous opinions; and they do also acknowledge that they came here purposely to propagate their said errors and heresies, bringing with them and spreading here sundry books, wherein are contained most corrupt, heretical, and blasphemous doctrines contrary to the truth of the gospel here professed amongst us."

Bellingham refused them food. He cut off their light by boarding up the prison window and refused them candles or writing material. Both were stripped and searched for signs of witchcraft. Boston would have been pleased to have hanged them had anything incriminating been found. To ensure that no one caught their radical ideas, the men in power declared that anyone attempting to speak with the women would be fined five pounds--a hefty chunk of change in those days.

These Quaker women had come by way of Barbados to publish the truth as they saw it. Now hunger gnawed their bellies and their prayers went up to heaven. It seems God heard, for the innkeeper bribed the jailer five shillings a week to smuggle food to the hungry women.

At the end of five weeks, Massachusetts brought the women out and sent them home on the ship that had brought them. The Captain was made to deposit 100 pounds as a guarantee that he'd return them to England. No doubt the Puritans hoped to make the transportation of Quakers a money-losing proposition for ship-owners.

Eventually, sterner measures were used against Quakers. Some were whipped; some were abandoned in forests; some had their ears cut off and some were hung. But Quakers kept coming; their persistence helped win America's civil rights.

Bibliography:

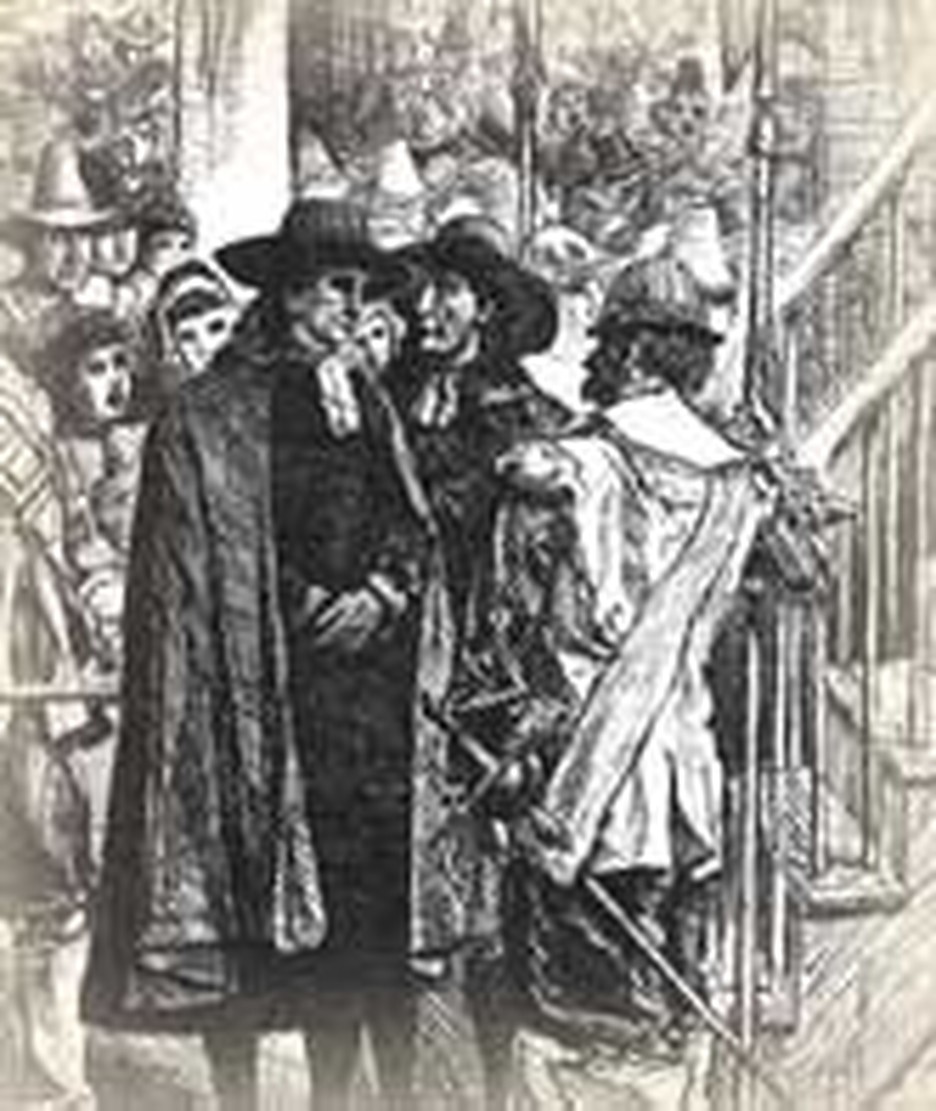

- Perry, William Stevens. History of the American Episcopal Church. Boston: James R. Osgood, 1885. Source of the Image.

- "Quakers, the. Hostile Bonnets and Gowns." http://www.mayflowerfamilies.com/ enquirer/quakers.htm

- Selleck, George A. Quakers in Boston, 1656-1964. Three centuries of Friends in Boston and Cambridge. Cambridge: Friends Meeting, 1976.

Last updated July, 2007.