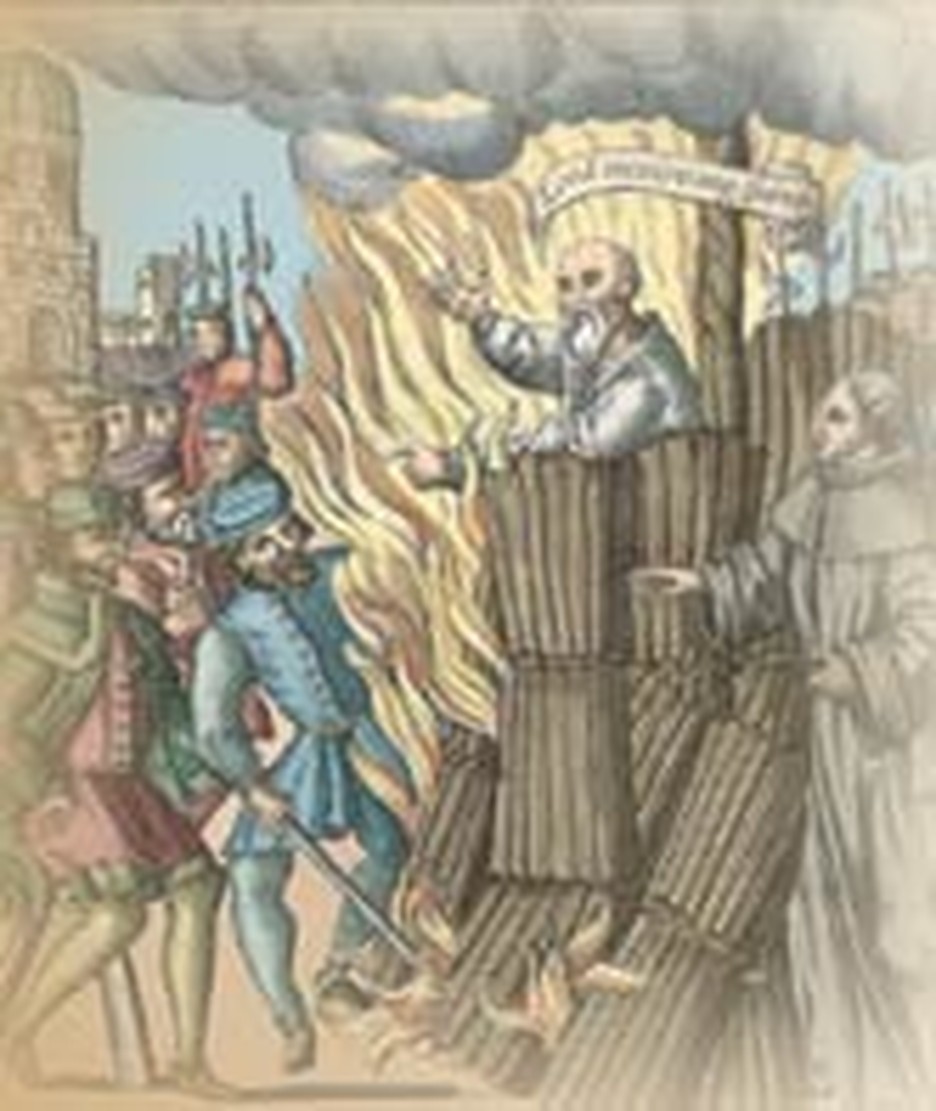

Before a vast crowd of friends and enemies, the Archbishop thrust his hand into the fire. He was going to his death by being burned at the stake but insisted that the hand that was guilty of such shameful sin must burn first. Jesus said "It is better to lose a limb than for your whole body to go to hell," and Cranmer took him at his word.

He went in style, but Thomas Cranmer was not a natural martyr.

Admittedly Thomas was committed to his Protestant faith in Catholic England at a time when that could be quite dangerous. And he rose to the highest position in the English Church, becoming the first Protestant Archbishop of Canterbury. But Thomas Cranmer loved his comfortable life of quiet scholarship. When it came to it, would he have the courage to take the ultimate stand for his faith? It was a close call. Here is his most unlikely story -- one that did much to shape the world of his day right down to our own day. Cranmer was born into a mildly well-to-do family in Nottinghamshire, England, in 1489. He studied at Jesus College, Cambridge, taking a surprising eight years to get his degree. After attaining his MA, he suddenly gave up any prospect of an ecclesiastical or academic career by marrying for love. When his wife Joan died in childbirth he was crushed, but Cranmer was destined as a result of this loss, to become possibly the most influential figure in the history of the English church.

Mission: Divorce

Thomas Cranmer was ordained at Cambridge and was still there at the time of Luther's encounter with Rome. He believed in reform, but from within the Catholic church, and he was horrified by Luther's separation from Rome. His mind was changed as a consequence of being drafted into the diplomatic service of the King.

Cranmer's mission was to get rid of Henry VIII's wife. Henry had married Catherine of Aragon with a special dispensation from the pope, because Catherine was his brother's widow, a match contrary to church law. But having borne him a daughter, Catherine failed to come up with any more children, and Henry needed a son to pass his crown on to. He believed the marriage was cursed by God, as Leviticus 20:21 warns, and another wife was called for. Normally, he would have come to another mutually satisfactory arrangement with the Pope, but the Pope was in serious trouble with Catherine's uncle, the Holy Roman Emperor, so no deal. Cranmer had the idea of canvassing the Protestant leaders of Europe and getting them to declare Henry's marriage invalid. This long debate was ultimately unsuccessful, but it had two huge results for Cranmer. It impressed the King enough to raise him to Archbishop of Canterbury, the top job in the English church -- to Cranmer's horror. And Cranmer was so impressed with the Protestants that he started to be gradually won over. Cranmer marked the change by quietly taking a second wife while he was out in Germany.

Cranmer at Canterbury

Parliament passed laws declaring the Church of England independent of Rome, making the King instead of the Pope, its head. Cranmer then declared the marriage void, and Henry took Anne Boleyn as his new wife. Cranmer had no political ambitions. Even as Archbishop, he spent three quarters of his working day in quiet study and found time in the remainder for sport. His greatest achievement at this time was to get English Bibles into the churches for the first time. In Henry's latter years, things got dangerous for Cranmer. Henry was never really converted to Protestantism, and the Church of England was really independent Catholic rather than Protestant. In 1539, the King issued the Six Articles, insisting that the beliefs of the Church of England were still well and truly Catholic. The bookies took bets that Cranmer would soon be executed like others who had fallen foul of Henry's whims. But the King respected Cranmer, and he retained his position. In January, 1547, Henry died, and was succeeded by his eleven-year-old son Edward VI. Edward was a convinced Protestant, and so Cranmer was retained and now had the opportunity to reform the church fully.

The New Prayer Book

Cranmer encouraged Protestant preaching in the church and published his own sermons. But Cranmer's greatest contribution to the Reformation was the Book of Common Prayer. This replaced the Catholic liturgy in Latin with new English services. The 1549 edition was pretty conservative, hoping not to upset the mass of people who were attached to Catholic traditions too much. But for this, it drew widespread criticism from Protestants, and so in 1552 Cranmer produced a revised prayer book, which was more emphatically Protestant. His Book of Common Prayer became one of the greatest classics of English Literature, and well into the twentieth century its phrases were part of the common currency of English people. Cranmer still kept in many elements of Catholic liturgy and ritual that he found beautiful and not unbiblical, and so the English services combined the best of old and new.

Cranmer the Heretic

Unfortunately for Thomas Cranmer's reforms, and for Cranmer himself, King Edward died in 1553. Lady Jane Grey was queen for a brief nine days before being swept aside by Edward's elder sister Mary. This was the one daughter that Catherine of Aragon had produced, and her life since then had not been happy. Not only had her mother been sent away, but when the marriage was declared invalid, Mary became "illegitimate." She was a fervent Catholic, and blamed all that had happened on Protestantism in general and Cranmer in particular. Mary set about restoring Roman Catholicism. When she replaced the English Prayer Book with the old Latin Mass, Cranmer protested and was arrested. In a humiliating ceremony, he was removed from office, but worse was to come. Barraged in jail by Roman Catholic apologists for three years, his confidence in his faith was crushed. Mary's men persuaded him to sign a series of six recantations. The first merely said that the English should obey their Queen's religion, but they became more and more serious and the last was a "root-and-branch" denunciation of Protestantism. In exchange for his life and freedom, the broken man signed. The capitulation of one of the greatest living Protestant leaders was a fantastic victory for Mary.

Surprise!

But now she made her great mistake. Her personal hatred for Cranmer was such that even though she had his recantation, she insisted on burning him anyway. The execution was on 21st of March, 1556, and Cranmer was allowed to preach before the massive crowd to publicize his recantation. In his last masterly speech, he repented of all his sins -- as he was meant to -- but ended by repenting his greatest sin of all, denial of the Protestant gospel. Amid uproar and commotion, he was led off to the fire and burnt. He put his right hand into the flames first. "As my hand offended," he said, "writing contrary to my heart, my hand shall first be punished."

What Might Have Been

The Roman Catholic Church convened the Council of Trent to counter the spreading Reformation influence. Cranmer eagerly desired that Protestant leaders meet together. He particularly sought unity on the Lord's Supper. He desired to host a meeting in England and on March 20, 1552, wrote and invited Calvin of Geneva, Bullinger (Zwingli's successor at Zurich) and Melanchthon (Luther's successor at Wittenberg). It never came to pass. July 24, 1553, Mary became queen. Cranmer's moment had passed. Below is an excerpt from his letter of invitation to Calvin.

Our adversaries are now holding their councils at Trent for the establishment of their errors; and shall we neglect to call together a godly synod, for the refutation of error, and for restoring and propagating the truth? They are, as I am informed, making decrees respecting the worship of the host; wherefore we ought to leave no stone unturned, not only that we may guard others against this idolatry, but also that we may ourselves come to an agreement upon the doctrine of this sacrament. It cannot escape your prudence how exceedingly the Church of God has been injured by dissensions and varieties of opinion respecting the sacrament of unity; and though they are now in some measure removed, yet I could wish for an agreement in this doctrine, not only as regards the subject itself, but also with respect to the words and forms of expression. You have now my wish, about which I have also written to Masters Philip [Melanchthon] and Bullinger; and I pray you to deliberate among yourselves as to the means by which this synod can be assembled with the greatest convenience. Farewell.

-- Your very dear brother in Christ,

Thomas Cranmer

From Cranmer's 1552 Prayer Book

Almighty and most mercyfull father, we have erred and strayed from thy wayes, lyke lost shepe. We have folowed too much the devises and desyres of oure owne hearts. We have offended against thy holy lawes. We have left undone those things whiche we oughte to have done, and we have done those thinges which we ought not to have done, and there is no health in us: but thou, O Lord, have mercy upon us miserable offendors. Spare thou them, O God, which confesse theyr faultes. Restore thou them that be penitent, according to thy promyses declared. unto mankynde, in Christe Jesu oure Lorde. And graunt, O most merciful father, for his sake, that we may hereafter live a godly, righteous, and sobre life, to the glory of thy holy name. Amen.

Almighty God, unto whom all heartes be open, all desyres knowen, and from whom no secretes are hyd: clense the thoughtes of our heartes by the inspiracion of thy holy spirit, that we maye perfectlye love thee, and worthely magnify thy holy name: through Christ our Lorde. Amen.

.jpg)