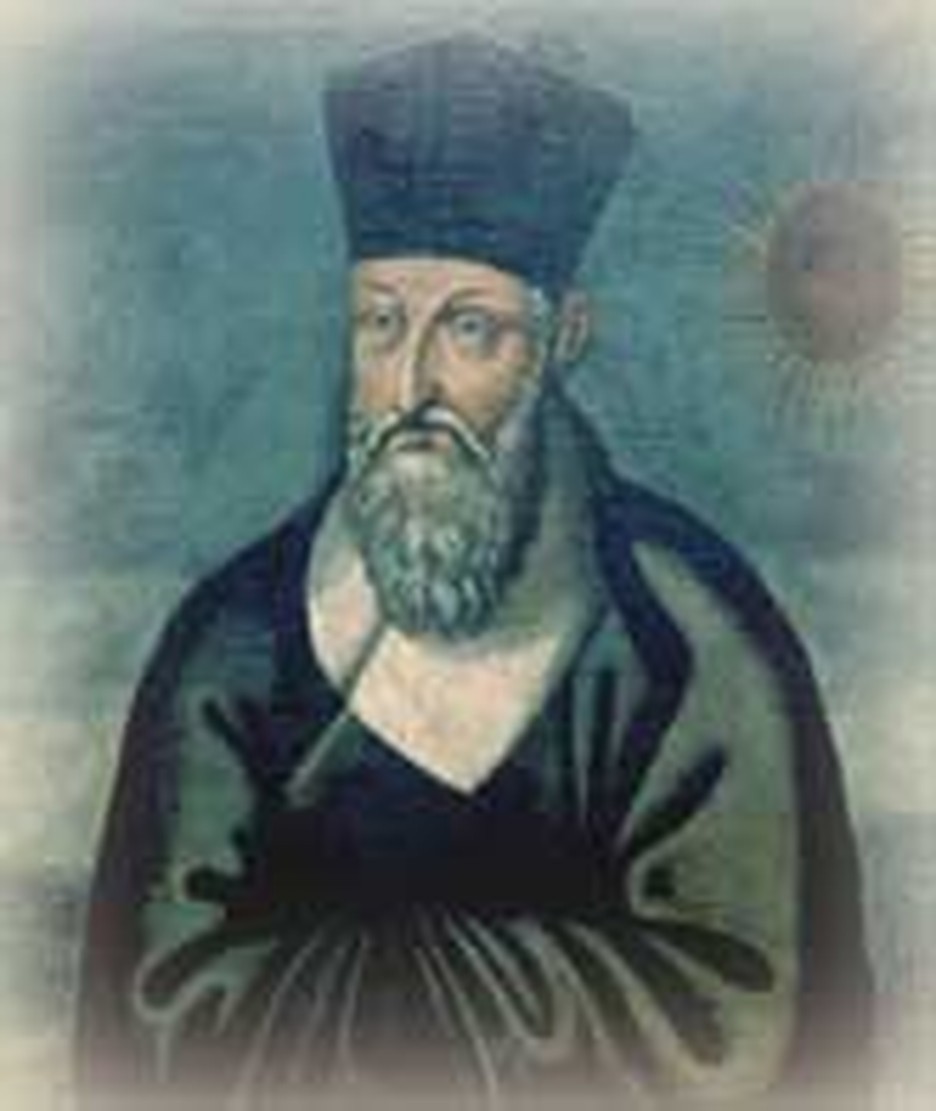

From behind, the man who boarded the sampan bound for China looked like a Buddhist monk. Seen face to face, it came as a shock that he was a westerner. A Portuguese trader, perhaps? But no, he wasn't pushing wares. The intelligence stamped on his face suggested something more scholarly. And who knows what might be in his bag?

In the 16th century, the Chinese prided themselves on being the most ancient civilization of the world--the only real civilization. They did not believe they had much to learn from foreigners. Chinese statesmen feared the destabilizing effects of religious innovations. Because of this, every attempt to introduce Christianity into China met with rejection. That is why Matteo Ricci was traveling disguised as a Buddhist monk. The gospel had to get to Peking and he thought he had found the right lures. Those lures were in his bag.

Ricci was born on this day October 6, 1552. The timing was perfect in light of the work he was to accomplish. Europe's artistic, scientific and technological advances that had begun in the Renaissance were well under way. Perspective had come to art. Prisms taught men the composition of light. Mathematics had been applied to physics. Mapmaking was a science. Architecture had transcended ancient forms. Printed books were now within the reach of the common man. Clock-making produced workable timepieces. Dipping into his bag, thirty year old Ricci dangled these Western inventions in front of his oriental hosts. Having aroused their interest, he spoke to them about Christ in the cultured Mandarin language, which he took pains to learn.

Tactfully, Ricci appealed to the words of the Chinese sages wherever they supported Christian doctrine. He even adopted a Confucian term for the name of God. All of this made the gospel more palatable to the Chinese and he met with considerable success. "Without going out of the house, we preach to the Gentiles, some of whom are converted."

Ricci and his associates devised a way to write Chinese phonetically. He translated several western works of science for the Chinese. Printed, these found their way into all China. With them went a primer on Christian doctrine.

His influence was so respected that at his death the emperor made him an honorary citizen of China. On his monument were engraved the names of hundreds of mandarins who revered him or had embraced his teachings. Centuries earlier, Nestorians had introduced Christianity to China. However it had failed. The lures dangled by Ricci helped him plant a church which has stood ever since. By his death there were 400 converts. Within fifty years, there were 150,000.

Bibliography:

- Anderson, Gerald H. Biographical Dictionary of Christian Missions. New York: Macmillan Reference USA; London : Simon & Schuster and Prentice Hall International, 1998.

- Brucker, Joseph. "Matteo Ricci." The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton, 1914.

- Durant, Will and Ariel. The Age of Reason Begins. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1961.

- Martin, Malachi. Jesuits; the Society of Jesus and the betrayal of the Roman Catholic church. New York: Linden Press, 1987; pp. 30, 33.

- O'Malley, William J. The Fifth Week. Loyola; p. 44ff.

- "Ricci, Matteo." The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. Edited by F. L. Cross and E. A. Livingstone. Oxford, 1997.

- Spence, Jonathan D. The Memory Palace of Matteo Ricci. New York, New York: Viking Penguin, 1984.

Last updated April, 2007.