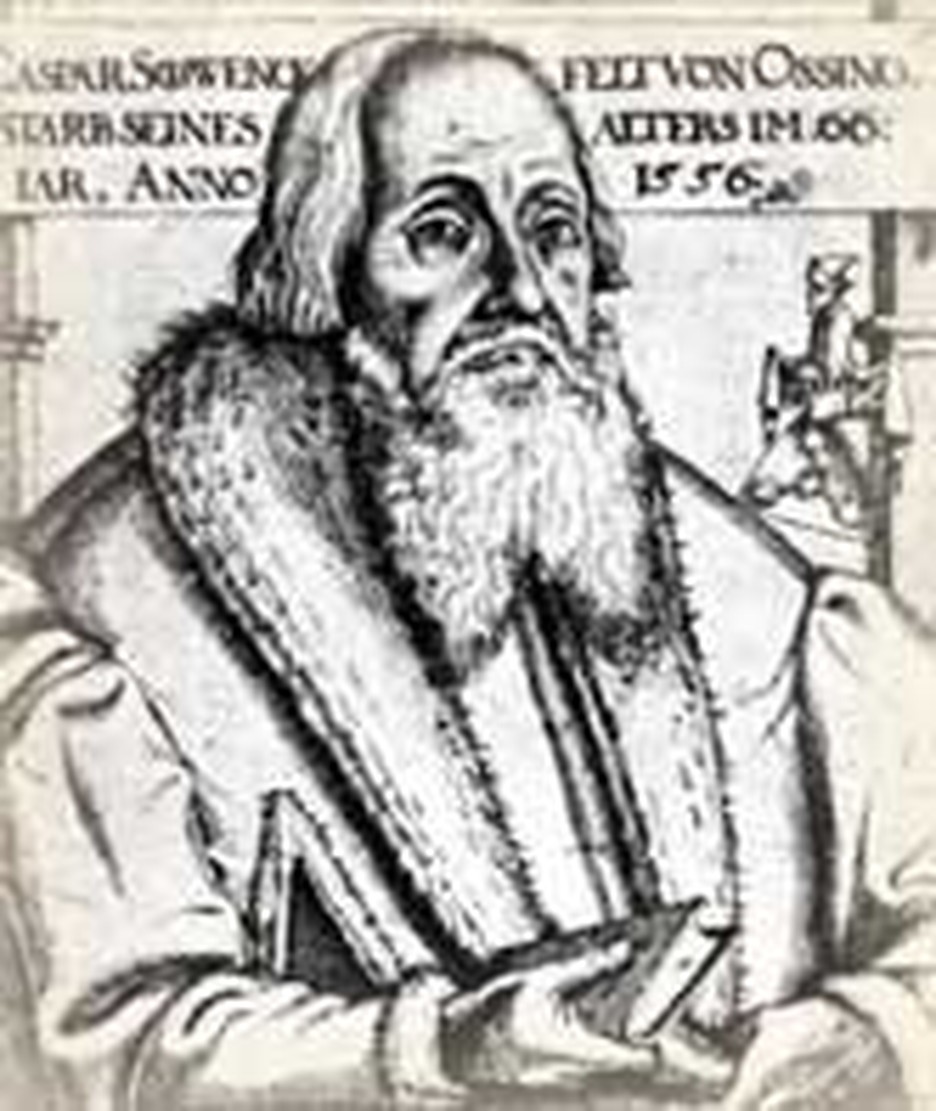

Two and a quarter centuries after Kaspar Schwenkfeld's death, which took place on this day December 10, 1561, small groups of his followers in Pennsylvania continue to follow his teachings. Who was this man whose influence has crossed continents and centuries?

Kaspar Schwenkfeld was born into the Silesian nobility in 1489, three years before Columbus' famous voyage. Silesia was a small province in central Europe. In 1519, Schwenkfeld experienced what he called a "visitation of God." He was deeply affected by the writings of Martin Luther and began a serious study of the Scriptures.

Committed to reform, he took strong action wherever he went. However, he wanted to reject only those elements of the old traditions which truly could be described as stumbling blocks to knowing Christ. He criticized reformers who went too far, too fast, and who seemed to think that only outward change was needed. To be a true Christian, one must change inside.

The more he studied the Scriptures, the more Caspar discovered areas of Luther's theology with which he disagreed. He especially had problems with Lutheran teachings on justification by faith alone, the freedom of man's will, and the futility of human works. Caspar also developed a unique understanding of the Lord's Supper which was distinct from Luther and the other reformers. He believed the true Christian at the Lord's Supper ate the spiritual body of Christ which would grow as a planted seed and transform the individual into the image of God and the person of Christ.

Caspar's main desire was to worship, praise and glorify Christ. He consciously strove to remain orthodox. Nonetheless, in 1541, when he published his Great Confession on the Glory of Christ, many considered the work heretical. He aimed at teaching people to unite with the real, living, spiritual Christ so that their lives would truly change. His position was more subtle than can be explained in this short article, but he taught that Christ has two natures, divine and human, the human nature being a kind of "celestial flesh" not fallen like ours. Jesus' human flesh was increasingly divinized while he was on earth, so he was eventually transfigured, resurrected and taken up to heavenly glory. It was Christ's invisible glorified flesh which Caspar thought believers ate at the Lord's Supper. Because of this view, his followers often called themselves "Confessors of the Glory of Christ."

The number of Schwenkfeld's followers diminished greatly after the Thirty Years' War in 1648. By 1700 there were only about 1500 remaining in lower Silesia. When the Austrian Emperor established a Jesuit mission to bring these back into the Catholic church, many fled Silesia, leaving their property and possessions behind. Some found refuge on the lands of Count Zinzendorf before coming to Pennsylvania in the 1530s. Five congregations of Schwenkfelders persisted in Pennsylvania at the start of the 21st-century.

Bibliography:

- Adapted from an earlier Christian History Institute story.

- Erb, Peter C. "The Life and Thought of Caspar Schwenckfeld von Ossig." Christian History, volume VIII Number 1.

- McLaughlin, R. Emmet. Caspar Schwenckfeld Reluctant Radical. New haven: Yale, 1986.

- "Schwenckfeldians." The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. Edited by F. L. Cross and E. A. Livingstone. Oxford, 1997.

Last updated July, 2007.