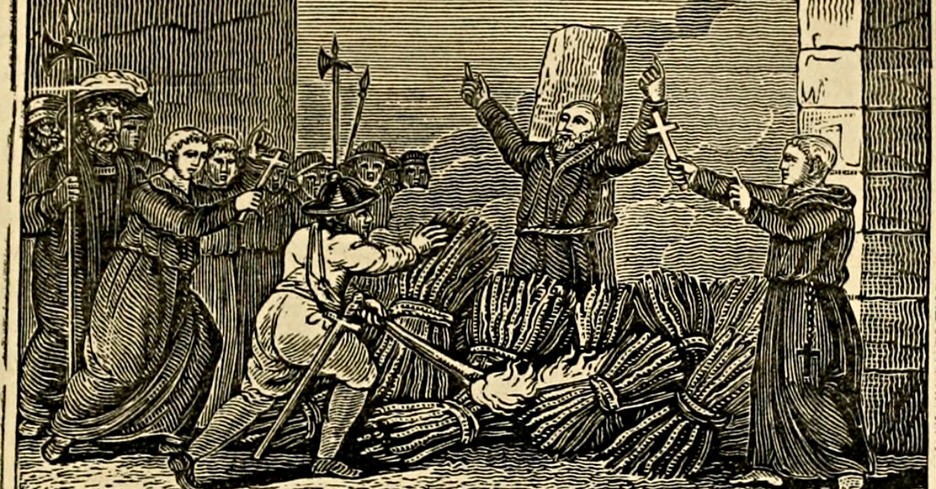

John Rogers was burned to death at the stake at Smithfield, England, on this Monday morning, February 4, 1555. Among the onlookers who encouraged him were his own children. Who was John Rogers, and what monstrous crime had earned him this cruel death?

Who was John Rogers?

Born about 1500, Rogers was educated at Cambridge. He became a Catholic priest and accepted a position in the church when the Protestant Reformation was in full swing. His conscience told him that certain teachings of his established Church were wrong, and he resigned, moving to Antwerp, Holland, where he ministered to English merchants.

In Holland, he became friends with William Tyndale, a reformer who was translating the Bible into English. Tyndale converted Rogers to Protestant views, and Rogers married. Nine months later, Tyndale went to prison; and he would be executed as a heretic. But Tyndale left a precious manuscript in John Rogers's keeping. This was his English translation of the books from Joshua to Chronicles which had not yet been printed.

Rogers was determined to see that Tyndale's valuable work was not lost. For the next twelve months he labored to put together a complete Bible. Its text was based on Tyndale and Coverdale, and its two thousand notes were borrowed from the writings of dozens of different reformers who were active on the Continent.

Tyndale had been declared a heretic, and his name could not go on the Bible. Rogers could not honestly claim the work as his own, so he used a pseudonym--Thomas Matthews. When Bishop Cranmer saw a copy of the new Bible, he was so excited that he asked Chancellor Thomas Cromwell to see if the king would license it. Henry VIII did. The Matthew Bible became the first officially authorized version in the English language.

After sickly Edward VI became king of England, John Rogers returned from the continent, fetching his wife to England. He was given high positions in the Church of England. Regrettably, he was one of those who agreed to burn poor, insane Joan of Kent to death (some of her claims were blasphemous). He was urged to show her mercy because some day he might need it himself, but did not listen.

Edward VI died. Mary, a Roman Catholic, became queen. John Rogers preached a stirring message, urging his congregation to remain loyal to Reformation principles. Mary's Catholic bishops questioned him about this sermon, but he answered well and was released.

The Martyrdom of John Rogers

However, churchgoers rioted when a Catholic was appointed to speak at Paul's Cross. The Mayor was present and could not restore order. The mob attacked Bishop Bonner, an eminent supporter of Queen Mary. Rogers shouted to the crowd to calm down and helped hustle Bonner to safety. Although no harm was done, the Queen's council was upset. They instructed the Mayor to prove he could keep order or said he must give up his office. The Mayor arrested Rogers, the one who had saved Bonner's life. Rogers spent over a year in prison, questioned several times about his beliefs by Lord Chancellor Stephen Gardiner.

According to Foxe's Book of Martyrs, Rogers begged Gardiner to let him speak a few words to his wife when the death sentence was passed. Gardiner refused, telling Rogers he was not legally married because he had once been a priest. However, as Rogers walked to the stake, singing psalms, he saw his wife at the roadside, holding their youngest baby, whom he had never met.

At the stake, Rogers was offered a pardon if only he would recant his beliefs and return to the Catholic church. He refused. The fire was lit and Rogers washed his hands in the flames as though he did not feel them. He was the first of many martyrs in Mary's reign.

Bibliography:

- Chester, Joseph Lemuel. John Rogers; the compiler of the first authorized English Bible... London: Longman, Green, Longman and Roberts, 1861. Source of the image.

- Foxe, John. Foxe's Book of Martyrs. Various editions.

- Loane, Marcus L. Pioneers of the Reformation in England. London: Church Book Room, 1964.

- "Rogers, John." Dictionary of National Biography. Edited by Leslie Stephen and Sidney Lee. London: Oxford University Press, 1921 - 1996.

Last updated May, 2007.