The pen is often as much to be feared as the sword. Throughout history, many nations have found it desirable to impose censorship. The church, too, has engaged in this practice.

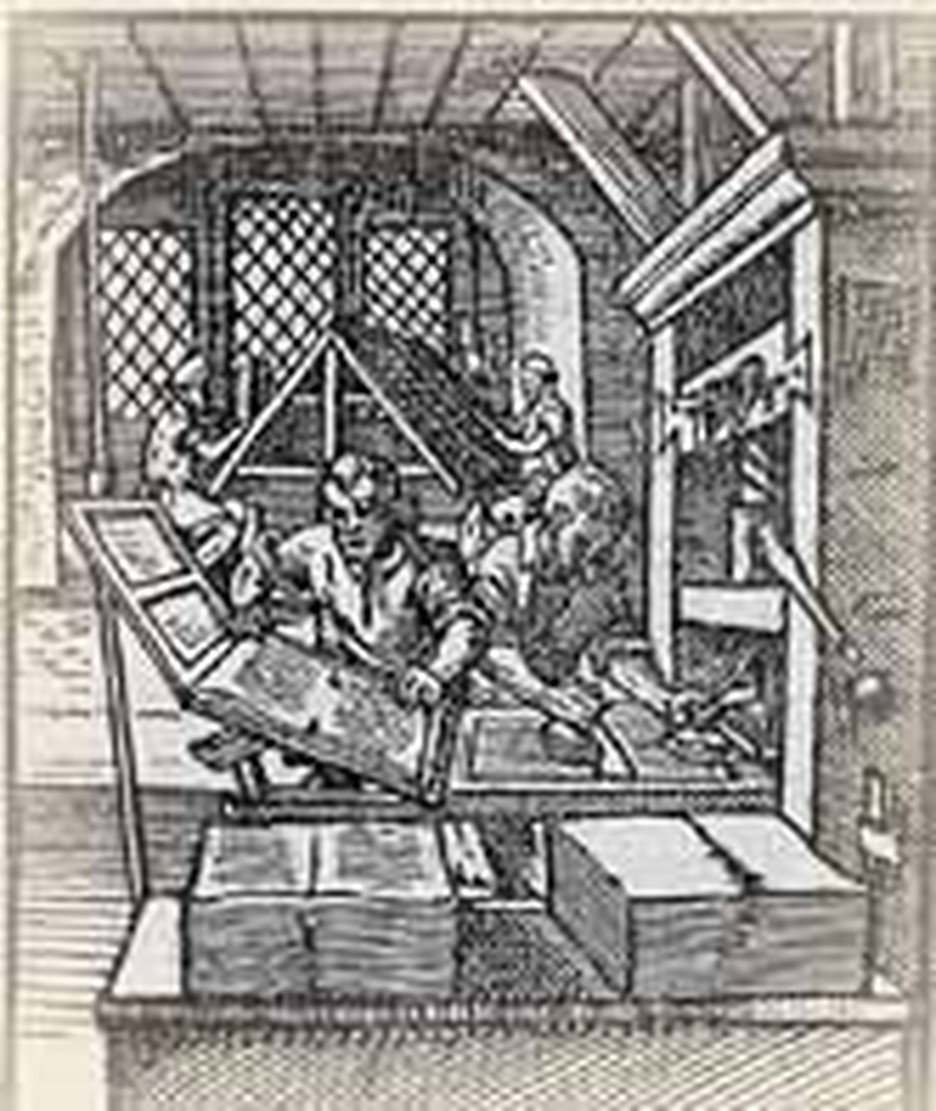

With the emergence of printing, a new danger to Christian unity and holiness was anticipated. Most early books were of a devout or educational nature. Indeed, the Bible itself was among Gutenberg's first projects. The serious tone of early printing could not forever endure. Within a mere sixty years of the invention of movable type, printed pornography had entered the market.

It was to respond to this danger that the 1515 session of the Fifth Lateran Council held in March, decreed that books should no longer be printed without ecclesiastical examination and consent. Every book published was to feature a license to print. This service would be rendered free by the church. Each bishop automatically became censor for his diocese.

Although the intention of the law was good, it was not pornography alone which would be affected by this decree. The council's ruling had more sinister implications. Various church authorities had already declared that scripture was not to be placed into the hands of the laity in their native languages. Would the council's ruling be used to prevent the Bible from being printed in vernacular languages?

Luther's theses were still two years away, so the council cannot have had him in mind. But the memory of John Wycliffe and Jan Hus may have lingered. Even without the benefit of the press, their popular ideas had lived on in the minds of men. The manuscripts of both had been burnt by the church and so had Hus himself. Wycliffe escaped the same fate only because powerful friends protected him. But his bones were dug up, burnt to ashes and cast on water. If works like theirs were to reach the market in thousands of identical copies instead of in a trickle of laboriously hand-copied rarities -- the councilmen must have shuddered.

Their decree was largely unenforceable. Months later, Luther posted his 95 theses and made masterful use of the new print technology to spread his theories across the breadth of Europe. His was Christendom's first media publicity campaign (although Erasmus had certainly shown the way). Under the protection of German princes, Luther could get away with ignoring the Lateran decree. William Tyndale, another reformer, had no such protection and had to resort to secret printing and pious smuggling. The underground press is not a new phenomenon.

The fifth Lateran Council broke up on March 16, 1517. As history shows, its decree was unable to prevent the spread of religious and scientific ideas. As for pornography, we know how it has fared. No one has yet found a way to ensure that only decent writings go to press.