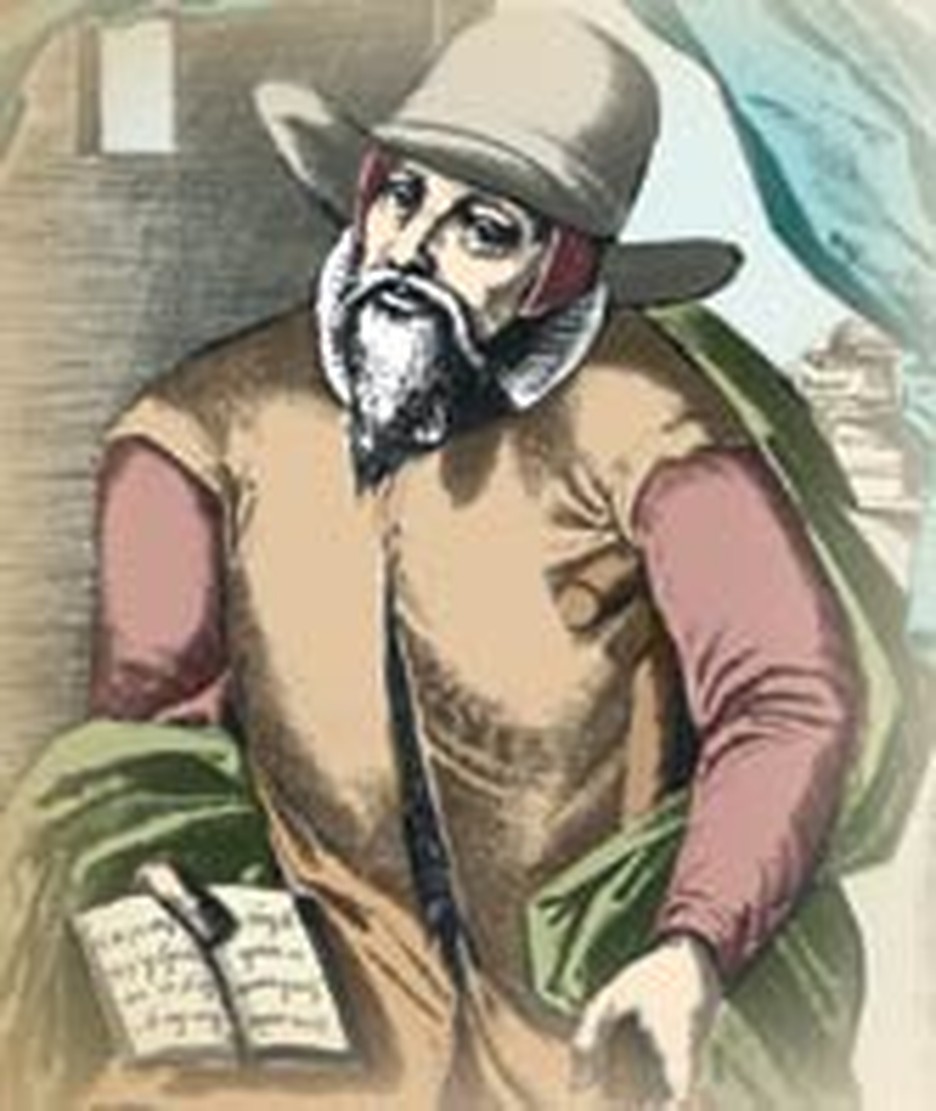

To know Menno Simons was dangerous; to befriend him, deadly. For sheltering Menno, Tjard Reynders was broken on the wheel. A ferryman was executed for bearing Menno down the Meuse River. Surely Menno Simons must have been a desperate criminal for mere accomplices to receive such stiff sentences!

Hardly! His "crime" was to interpret the Scriptures differently from his neighbors. He believed that only those who had reached an age to understand their action should be baptized; that faith was worthless unless demonstrated by works. For these two "heresies" a reward of 100 golden guilders was placed on his head and he was harried from refuge to refuge through Northwest Europe.

A Troubled Dutch Priest

Menno Simons early career did not suggest his later notoriety. Born in the Netherlands a few years before Luther posted his famous Ninety-Five Theses, Menno matured in an age of ferment. At his parents' wish he prepared for the Roman Catholic priesthood. His studies grounded him in Greek and philosophy, but not the Bible. That book he feared to open. Ordained when 28, Simons embarked upon a routine of masses, infant baptism, services for the dead--not to mention drinking, card-playing and other frivolities. But reformation hovered in the air.

Outwardly conformed to his church, Menno struggled inwardly to believe that bread and wine became Christ's literal body and blood. For two years he was in torment of mind. Finally, fearfully, he opened the Bible to see what it said. To his dismay he found no direct support for this doctrine of transubstantiation. Now he was in deeper distress than ever. To deny the doctrine of the church, he thought, was to incur sure damnation. Yet if the Bible were God's Word . . . . In desperation he opened a forbidden work by Luther. No man could be damned for violating the commands of men, said Luther. Relief flooded Menno's soul. He decided he would trust the scripture.

Comfort in Conformity

Still he did not break with the church. Not for ten more years would he do that. Later Simons admitted that he had enjoyed comforts too much to make the break. All the same he continued to read the Bible and acquired a reputation as a good man and Bible preacher. But a new crisis was developing within him.

In 1525 a Zurich group concluded infants should not be baptized. Called Anabaptists (re-baptizers) they faced immediate persecution. The whole of Europe, Catholic and Protestant Reformed, accepted infant baptism. Sicke Freerks, an Anabaptist tailor, was beheaded for receiving re-baptism. His martyrdom shook Menno. In Freerks he saw a man willing to die for his faith. Menno pored over his Bible, studying baptism, and concluded the Anabaptists were right; but he did not join them.

Anabaptist Excesses

This is not surprising. Many peasants interpreted freedom of conscience as freedom from restraint. Under the cloak of Anabaptist ideas, they revolted, seizing the city of Munster. After a cruel siege they were massacred. Europe's rulers, fearing an uprising of the lower classes, hounded all Anabaptists as insurrectionists.

Menno Simons preached against the errors of the Anabaptist revolutionaries. Yet he knew himself a hypocrite, without the strength of spirit to deter others from joining violent sects. Tragedy finally precipitated his break with Rome.

Taking a Stand

A group of radicals took up swords and occupied an old cloister where they were eventually massacred by troops. Menno's conscience smote him. These men were willing to die for a lie while he, Menno, would not suffer for truth. He fell to his knees, pleading for forgiveness, and rose, determined to preach unadulterated truth. For nine months he spoke boldly from his pulpit before voluntarily resigning his priesthood.

Then for a year he lived in seclusion, studying the Bible, until brethren begged him to shepherd them. After a severe struggle within himself, for he guessed what he must suffer, he agreed. It was a fateful decision. Decent Anabaptists from Northern Europe noted his common sense and turned to him. He kept the movement from degenerating into fanatical cults. Traders and tinkers took up his teaching and it spread.

Menno Simons, a Hunted Outlaw

Charles V offered 100 guilders for Menno's capture, forbade the reading of his works, and made it illegal to aid or shelter him. Menno's followers were to be arrested. Criminals were offered pardon if only they would betray him.

Menno lived on the run, unable to find in all the country a hut "in which my poor wife and our little children could be put up in safety for a year or two." Two of his three children died before him. Friends were slain. Men he had succored turned against him over doctrinal differences.

In spite of these woes, Menno continued to lead his people. He wrote simple books to meet their spiritual needs. Unlike others who bore the name Anabaptist, his followers remained law abiding. Eventually the authorities saw the distinction and named his followers Mennonites.

Menno's wife died. He became crippled, hobbling with a crutch. Yet he labored for Christ, urging others to repent and lead pure lives. He renounced war, called for separation of church and state, and pleaded for freedom of conscience. All people must accept Christ's sovereignty and the church must be a faithful witness for Christ.

Menno Simons died in 1561, having eluded capture to the end. Not a great theologian, he was nonetheless a man of powerful influence, for he lived as he preached. Authorities largely agree he steered the Dutch and nearby German Anabaptists from fanaticism and disintegration. His ideas survive with the Mennonites, Amish and Hutterites, and influenced other Protestants such as the Baptists.

In HIS OWN WORDS: MENNO Simons on the NEW BIRTH

Do you suppose, dear friends, that the new birth consists of nothing but in that which the miserable world hitherto has thought that it consists in, namely, to be plunged into the water; or in the saying, "I baptize thee in the name of the Father and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost"? No, dear brother, no. The new birth consists, verily, not in water nor in words; but it is the heavenly, living, and quickening power of God in our hearts which flows forth from God, and which by the preaching of the divine Word, if we accept it by faith, quickens, renews, pierces, and converts our hearts, so that we are changed and converted from unbelief to faith, from unrighteousness to righteousness, from evil to good, from carnality to spirituality, from the earthly to the heavenly, from the wicked nature of Adam to the good nature of Jesus Christ.

Baptists and Anabaptists: What's the Difference?

They are two separate and distinct movements but share some common convictions such as the rejection of infant baptism and separation of church and state. The Anabaptists had their beginnings in the early 1520s in Zurich, Switzerland, as a splinter group from Zwingli's reform movement there. The modern Baptists began in England in 1609 under John Smyth (c. 1554-1612). Some of them sought refuge in Holland in their early years and came into direct contact with Anabaptists there, and these Baptists were no doubt influenced by them to some degree. However the two movements remain distinct to this day.

Fascinating Facts

- Anabaptists and Mennonites offered such powerful witness at their executions that these were increasingly carried on in secret with the martyrs gagged. Since some managed to free their tongues a clamp was placed over their tongue and the tip burned so it could not slip back through the vise.

- Because Mennonites stressed that one's life must show the results of one's conversion, many descendants, lacking the original fire, became legalistic.

- Baron Bartholomew von Ahlefeldt of Denmark, deeply impressed by Mennonite faith under persecution, opened his lands to their refugees. When the King of Denmark urged him to expel them, he refused. Menno was one of those who took refuge on the baron's lands.

- One of the radicals killed at the Old Cloister was Peter Simons, believed to have been Menno's brother. This would help explain the soul-shaking effect the massacre had on Menno.

- Menno's last years were troubled by the question of shunning (excommunication) on which he urged moderation. Deep divisions threatened the Mennonites. So troubled was Menno, he said only God's grace prevented him from losing his reason. "There is nothing on earth I love so much as the church; yet just in respect to her I must suffer this great sorrow."

- Menno held semipublic debates with Reformed and Lutheran leaders and also wrote books showing in what particulars his beliefs differed from theirs.

- About 30 of Menno Simons' writings survive as well as several letters. His books include Christian Baptism, The True Christian Faith, and The Cross of the Saints. One 10-page work bears the haunting title: A Pathetic Supplication to All Magistrates and pleads for kindness toward his persecuted people.