The believers from the City of Rome were solemn. Under persecution, many Christians had been killed at various times. "Witnesses," they called these martyrs. The bodies of two witnesses who died in exile had come home on this day, August 13, 236.*

When Maximinus Thrax was Roman emperor, he exiled Pontianus and Hippolytus to the island of Sardinia where they probably slaved in the mines. There they died, but now their remains had been brought back for a decent burial. Pontianus, who had been Bishop of Rome until his exile, was laid in the tomb of Callistus, an earlier Bishop of Rome (they would come to be known as popes, from the Italian for "father"). Hippolytus, who had also been a bishop in or near Rome, was buried somewhere along the Tiburtine Road.

Of the two, Hippolytus' story is more interesting because we know next to nothing about Pontianus. Hippolytus was the most important theologian of the Roman Church up to that time, although his work was shelved for centuries afterward because it was written in Greek which the people of the West forgot how to read. One of his books was against heresy. In it he explained what the Gnostics (who believed they were saved by secret knowledge) and other groups taught and showed where they went wrong.

This would be enough to make Hippolytus worth remembering. But above all that, his case is often cited in arguments regarding the authority of the Roman Church and its claim that popes are infallible when speaking ex cathedra.

To begin with, Hippolytus was a "great-grandson" of St. John the Apostle. That is, we can trace his line of apostolic succession directly to John. He was commissioned by St. Irenaeus, who was commissioned by Polycarp, who was commissioned by (or at least personally knew) St. John himself. So there can be no question about his legitimacy as a bishop.

From the fourth century on, the Roman Church venerated Hippolytus as a saint. Even popes have acknowledged him as a saint. Yet he was also the first antipope (one "illegally" elected at the same time).

How could this be? Hippolytus spoke out strongly against the wrongdoing, cruelty and doctrinal errors of the bishops of Rome. This struck a responsive chord with the Roman population, who elected him Bishop of Rome in opposition to Bishop Callistus. Hippolytus continued in opposition to the bishops of Rome until he went into exile. While in exile, there are indications that he was reconciled with Pontianus.

Hippolytus was an expert on heresy. The fact that he insisted that some of the popes of his day were heretics was a strong reason that many scholars could not agree when the Vatican Council declared the popes infallible in 1870.

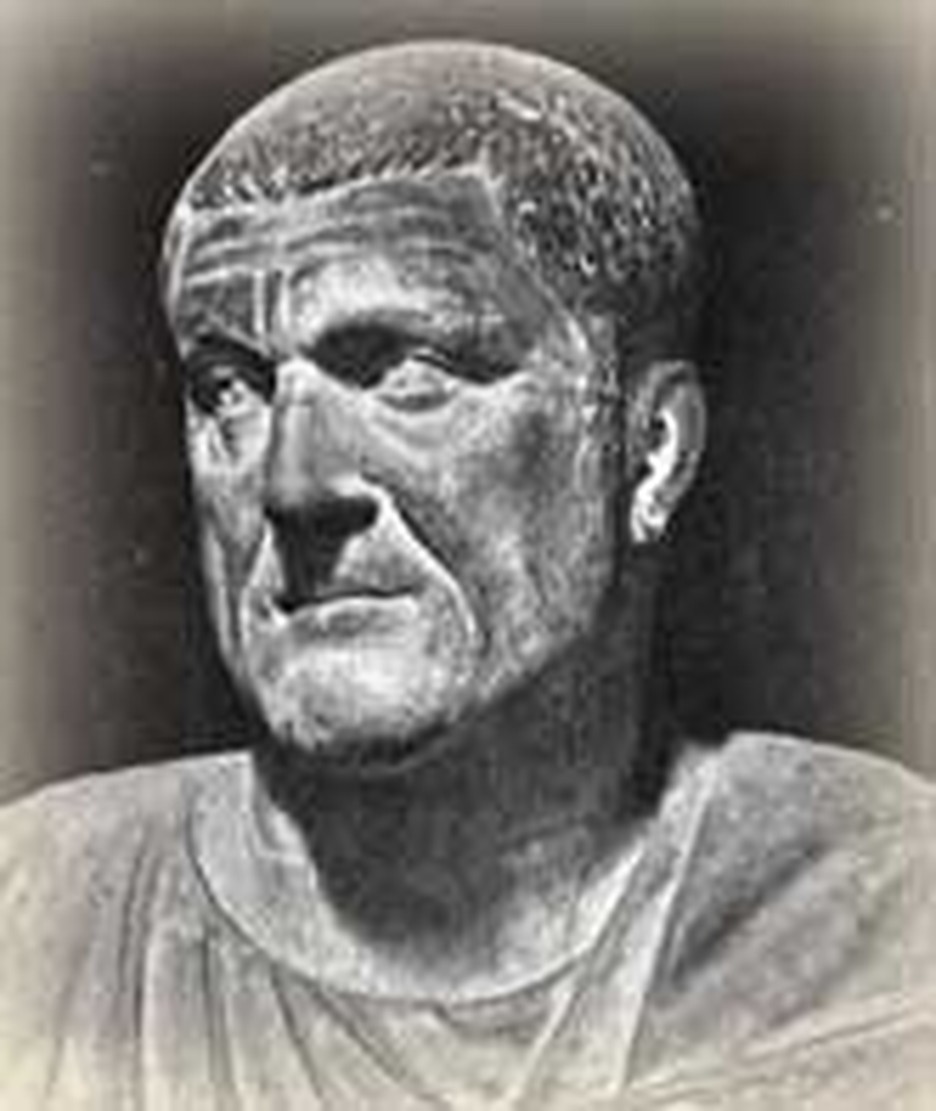

In the sixteenth century, workmen digging near an ancient church on the Tiburtine Road uncovered a marble statue. This was of a bishop seated in a chair, wearing a pallium (a cloth that symbolizes full episcopal authority). Pope Pius IV declared it to be Saint Hippolytus. Carved on the back of the chair were a list of Hippolytus' writings.

*Although the day seems fairly secure, the year is open to question.

Bibliography

- Aland, Kurt. Saints and Sinners; men and ideas in the early church. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1970.

- The Ante-Nicene fathers: translations of the writings of the fathers down to A.D. 325. Edited by Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson. American reprint of the Edinburgh edition. Revised and chronologically arranged, with brief prefaces and occasional notes, by A. Cleveland Coxe. New York : Scribner's, 1926.

- Durant, Will. Caesar and Christ. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1944; especially at pp. 617-18.

- Hippolytus. The Apostolic tradition of Hippolytus,

translated into English with introduction and notes by Burton Scott

Easton.

Cambridge [Eng.] The University press, 1934. - Kirsch, J. P. "St. Hippolytus of Rome." Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Appleton, 1914.

- Rostovtzeff, M. Social and Economic History of the Roman Empire. Oxford: Clarendon, 1926.

- Various church histories, web articles, and histories of the popes.

Last update June, 2007