Who was John Calvin?

"There is not one blade of grass, there is no color in this world that is not intended to make us rejoice." Those words were penned by a man who has been accused of generating a joyless Christianity. He is remembered as the man who taught predestination, an idea repugnant to many modern minds. Yet those who know Calvin well regard him as a saint. And they aren't surprised that he made such a statement about colors and grass.

Born in France in 1509, Calvin was quite brilliant. Initially, he intended to be a priest, but he entered the field of law, studying at different universities, including Paris.

Calvin's Major classic at 27

About 1533, Calvin had a "sudden conversion." He said: "God subdued and brought my heart to docility." Apparently, he had encountered the writings of Luther. He broke from Catholicism, left France, and settled in Switzerland as an exile. In 1536, Calvin published the first edition of one of the greatest works ever written, The Institutes of the Christian Religion. At the age of twenty-seven, he had already produced a major systematic theology, a clear articulation of Reformation teachings.

His writings impressed Guillaume Farel, the Reformer of Geneva, Switzerland. Farel pressed Calvin to come and help the Genevan reform. Geneva was to be Calvin's home until he died in 1564 (except for a three-year period when he was exiled from there, only to be invited back to leadership).

While there, his workload was staggering. Calvin pastored the St. Pierre church, preaching in it daily. He produced commentaries on almost every book of the Bible. He wrote dozens of devotional and doctrinal pamphlets, carried on vast correspondence, and trained and sent out scores of missionaries. (He managed to do all this while constantly battling various ailments, including migraine headaches.)

The reformer wanted Geneva to be like the kingdom of God on earth. He had his work cut out for him. The Genevans had had notoriously lax morals before his coming, and they often balked at his attempts at improving morality. But Calvin's influence was everywhere-in schools, notably, but also as a kind of overarching presence, because he urged excommunicating church members whose lives did not conform to spiritual standards. And every citizen of Geneva had to subscribe to his confession of faith that had been adopted by the city council.

A School for many Nations

Geneva became a powerful moral magnet, attracting Protestant exiles from all over Europe. The Scot, John Knox, described Geneva as "the most perfect school of Christ since the days of the apostles." Through his moral authority, Calvin truly reformed Geneva. And through his French and Latin writings - the Institutes in particular - he gave Protestantism amazing vigor.

What is so grand about the Institutes? For one thing, no other Reformer ever stated Protestantism's beliefs so clearly. Luther wrote much, but never in one book did he bring all key beliefs together. Calvin's book -- which he kept enlarging throughout his life -- covered all the bases.

The Difficult Doctrine

Book III of the Institutes has received much attention. In considering the Holy Spirit, Calvin examined the doctrine of regeneration: how are we saved? He claimed that salvation is only possible through the grace of God. Even before creation, God chose some people to be saved. This is the bone most people choke on: predestination. Curiously, it isn't particularly a Calvinist idea. Augustine taught it centuries earlier, and Luther believed it, as did most of the other Reformers. Yet Calvin stated it so forcefully that the teaching is forever identified with him. Calvin said it was clearly taught in the Bible.

For Calvin, God was -- above all else -- sovereign. Like all the Reformers, he hated how Catholicism had degenerated into a religion of salvation-by-works. So Calvin's constantly repeated theme was this: You cannot manipulate God nor put Him in your debt. If you are saved, it is his doing, not your own.

The Fruits of Election; The Right to Revolution

God alone knows who is elect (saved) and who isn't. But, Calvin said, a moral life shows that a person is (probably) one of the elect. Calvin was intensely moral and energetic, and he impressed on others the need to work out their salvation - not to be saved but to show they are saved. This emphasis on doing, on acting to transform a sinful world, became one of the chief characteristics of Calvinism.

In emphasizing God's sovereignty, Calvin's Institutes lead the reader to believe that no person -- king, bishop, or anyone else--can demand our ultimate loyalty. Calvin never taught explicitly that men have a "right" to revolution, but it is implied. In this sense, his works are amazingly "modern."

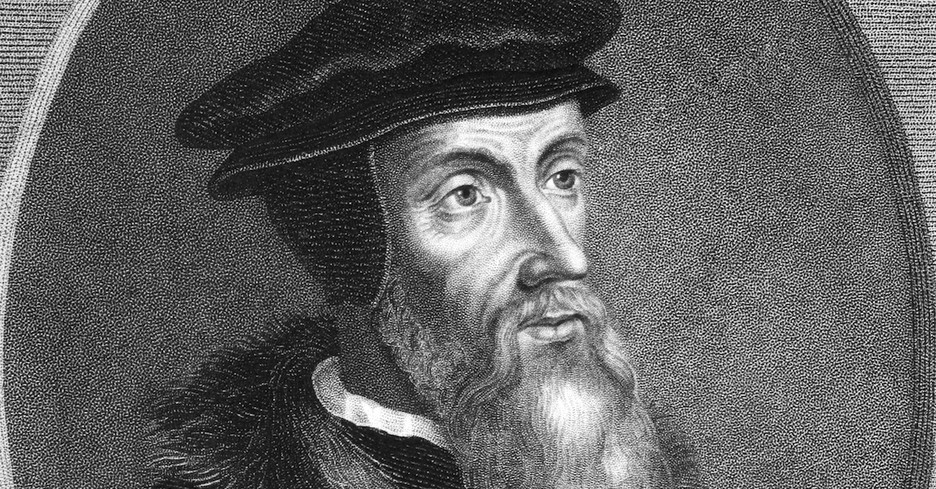

Pictured Below: Portrait of John Calvin

Far-reaching Influence

Countless volumes have been written about Calvin's influence, some applauding the man, while others regard him as a puritanical fiend. But it is safe to say that few Christians have been more brilliant, energetic, sincere, moral, and dedicated to the church's purity.

Calvin's theology imported better than many other brands of Protestantism. It found a home in places as far apart as Scotland, Poland, Holland, and America. His spiritual descendants make up the World Alliance of Reformed Churches based in Calvin's Geneva. This worldwide alliance consists of 178 denominations with over 50 million adherents in more than 80 countries.

Marriage and family |

Adapted from Christian History Institute's book, 100 Most Important Dates in Church History, published by Revell. Photo credit: ©GettyImages/GeorgiosArt