The Pilgrims and Puritans were both groups united by their dedication to worshiping God freely, yet they pursued this calling in different ways. Both groups trusted in God’s providence, yet their differing approaches show how faith can lead to various expressions and paths, all ultimately seeking to honor and follow His word. To understand the Pilgrims versus the Puritans, we must start with what they had in common. Both groups originated in England. Then in the 17th century, they both emigrated to the American colonies.

Similarities Between Pilgrims and Puritans

The Puritans strove to “purify” the Church of England by ridding it of Roman Catholic traditions. Church of England officials sent the first Puritan ministers to America with mixed blessings and opinions about changes in the church. They arrived in America after the Pilgrims, but in greater numbers and with more resources to support their economic growth. They immediately conflicted with French Roman Catholics and Native Americans. Puritans also came to the New World in much greater numbers with more resources to support their economic growth.

The Pilgrims (who historians refer to as Separatists) sought separation from the Church of England. Their group grew out of the larger Puritan movement, becoming a distinct group as they sought different goals. British officials persecuted them for worshipping God in a manner that didn’t fit Church of England tradition, so they came to the New World to enjoy religious freedom. The Pilgrims were a much smaller, humbler bunch that did not thrive economically in England or the Netherlands. Pilgrims may have worn buckled shoes and black hats, which were popular in England at the time, but such items would have been beyond most Pilgrims’ budgets. Most likely, Pilgrims wore blue, green, or orange clothing from plant-based dyes.

When they arrived in America, they blended peacefully with existing Native American and French cultures already established in the New World.

Both Pilgrims and Puritans found religious freedom, economic growth, and adventure in colonial America. They were challenged with serious illness, hunger, and danger from the unknown wilderness and its people. Their religious beliefs united both groups of colonists, holding them together spiritually in their struggle to survive.

Differences Between Pilgrims and Puritans

Puritans spread their spiritual practices and Protestant work ethic for centuries in early America. Rockwell Stensrud observed in a 2015 Newsweek article, “What’s the Difference Between a Pilgrim and a Puritan?” that a key Puritan legacy was that they “introduced New England to a lingering burden of guilt and existential angst.” Stensrud writes that the Massachusetts Bay Colony Puritans believed in Manifest Destiny, the idea that God promised to give them exclusive rights to the early American territory. At the same time, Puritans viewed the colonial wilderness as “the Devil’s playground,” while the Pilgrims befriended and learned to farm from Native Americans.

Puritans established towns around Boston run jointly by British magistrates and Congregational clergymen. It was a formidable government. Puritan judges hanged dissenters, including 19 people convicted of practicing witchcraft in the late 17th-century community of Salem, Massachusetts. The convictions were based on “spectral evidence”—signs of the Devil reported by the family members and neighbors—rather than solid proof. The term ”witch hunt” still refers to any investigation that plays on a community’s fears of a group’s unpopular ideas. Many of the Salem people accused of witchcraft were eccentric and either young or very old. As depicted in Arthur Miller’s play The Crucible, middle-aged people may have been accused of witchcraft so neighbors could seize their property.

Puritans rigidly enforced their values based on their ministers’ interpretation of the Bible. Strict, supposedly Christian morality—with a high interest in judging others and scant recognition of the forgiveness of sins—is still referred to as “Puritanical.” In contrast, the Pilgrims believed in the doctrine of free will acknowledged by the Church of England. They welcomed other cultures. Plimouth Plantation Associate Director Vicki Oman writes, “The Pilgrims never really expressed the desire to convert the rest of North America to their way of thinking.”

Native people were overwhelmed by many Puritans settling in the colonies. While the surviving “ragtag” Mayflower Pilgrims accepted help from the Wampanoags and celebrated the first Thanksgiving feast with them, there were no joyful gatherings of Puritans and Native Americans. Friendship with others was not on the Puritan agenda. They appeared arrogant and sometimes aggressive, with no intention of sharing food or land.

When Did the Pilgrims Come to America?

In 1534, adopting the ideas of the Protestant Reformation, the Church of England replaced a sovereign pope with a sovereign king. Many rituals from Roman Catholicism remained in worship services. Separatists, worshipping God in a secret and simpler style, were charged with treason and prosecuted if caught. They were punished with jail time or death. Eventually, the persecution caused about a hundred Separatists to leave England for the Netherlands in 1607-1608.

While today we call these brave Separatist emigrants “Pilgrims,” the term wasn’t used until around 1800, when citizens of Plymouth, Massachusetts, organized what became an annual celebration of the founding of Plymouth Colony. Before 1800, the Pilgrims were called “first-comers” or “forefathers.”

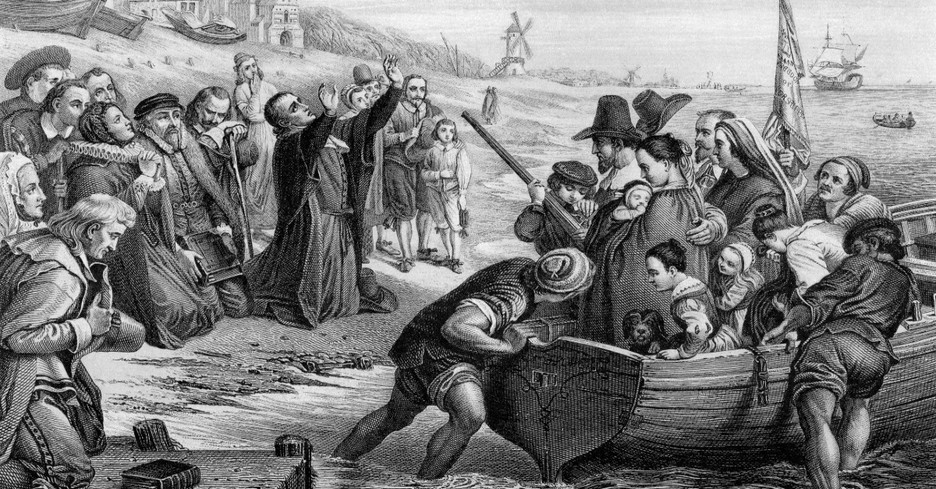

After roughly 12 years in the religiously tolerant but culturally different Netherlands, the Pilgrims sought a home in the New World. Half the passengers who sailed out of the Netherlands on the Mayflower were Separatists, Pilgrims seeking religious freedom. The other half were laborers, soldiers, and craftsmen whose skills were required to cross the ocean in a ship and build a new home when they landed in the British colony.

It was a difficult voyage, but the Pilgrims landed near Plymouth Rock in 1620. In “Spirits of Our Forefathers - Alcohol in the American Colonies,” Tom Jewett writes that the Mayflower was charted to land in Virginia but landed in Plymouth, Massachusetts, to preserve enough beer for sailors returning to the Netherlands. During the Pilgrims’ first year in the New World, half of the 102 original voyagers died—mainly from disease, starvation, and exposure to the harsh climate.

During their second year living in the American colony, native Wampanoag people taught the Pilgrims how to fish and harvest crops in their new land. The storied Thanksgiving feast attended by natives and colonists was celebrated in November 1621. Six months before Thanksgiving, the Wampanoags and Pilgrims had signed a peace treaty, which led to the survival lessons provided to the Pilgrims by the Wampanoags. When tribal leadership changed in 1675, the harmonious relationship ended. King Philip’s War broke out in the colonies, with very high casualties for colonists and Native Americans.

European and Native American relations had some dark episodes before King Philip’s War. In the 16th century, Native Americans welcomed French fur traders. The Wampanoags’ positive attitude toward Europeans changed after 1614 when Captain Thomas Hunt kidnapped and sold a group of Wampanoags into slavery in England. Around 1616, an unknown disease likely brought by European fur traders killed many Wampanoags and other Native American tribes in the region (possibly two-thirds of the population). Lack of good hygiene likely contributed to the spread of disease, both before and after the Puritans and Pilgrims arrived. History.com contributor Becky Little explains how Native Americans bathed regularly and cleaned their teeth with wooden chew sticks and fresh herbs, while European colonists thought cleanliness was more about cleaning their undergarments and bed linens than cleaning themselves. The Pilgrims’ attitude about alcohol probably also contributed to health issues. New York Daily News contributor Keri Blakinger notes how the Pilgrims also considered beer healthier and safer to drink than water (even for children), drinking much more alcohol than we do today.

The Pilgrim-Wampanoag peace treaty was never based purely on love for fellow humans. By 1620, when the Pilgrims arrived in the Plymouth colony, Wampanoag disease and slavery losses had provided an opportunity for a rival group of Native Americans, the Narragansetts, to try to overtake the Wampanoags. Though suspicious of Europeans, Wampanoags leaders made a peace treaty with the Pilgrims to gain protection from the Narragansetts.

When Did the Puritans Come to America?

The first Puritans arrived in the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1630 in 17 ships carrying over 1,000 passengers. History.com contributor Dave Roos observes that besides wanting to reform the Church of England, the Puritans “came with money and resources and divinely inspired arrogance.” Ten years later, 20,000 people who identified as Puritans lived in the colony. The Pilgrim population at that time numbered only 2,600. As a result, Puritan culture dominated the colony. The Puritans were more numerous, better funded and educated, and more controlling of their new territory than any other group in the New World.

Puritan ministers and heads of families demanded conformity in religious beliefs and personal values. They were determined to create a City on a Hill, a New Jerusalem in the New World. Puritan leader John Winthrop used this language in a 1630 sermon given on the Arbella. Before his people had even reached the colony, he advised them that they were a “city on a hill” and that all the world’s eyes were watching them. The Puritans believed they were God’s elect—a special, chosen people, similar to the Nation of Israel in the Old Testament. The early American Puritan community saw itself as a theocracy in which the church governed the people.

Puritans and Pilgrims worshipped God the “congregational way”—without a prayer book, recited creeds, or recognizing a pope or king. A “covenant” united the congregation, focusing on Jesus Christ, revealed through God’s Word. Congregationalists chose their church leaders democratically, a practice that led to government formation ideas in America.

Why Do The Puritans and Pilgrims Matter Today?

San Francisco State University historian Sarah Crabtree argues that people conflate the Pilgrims and the Puritans in retellings of the first Thanksgiving. For one thing, The Puritans “explicitly rejected religious freedom and never attempted to adopt the Pilgrims’ initial, fleeting cooperation with American Indian peoples.” As mentioned earlier, the peace between the Pilgrims and Native Americans didn’t last, with bloody battles ending the harmony.

Yet, 400 years later, we still look back at the initial time of peace between two cultures with hope. Crabtree thinks our Thanksgiving observation owes itself to the Pilgrims’ sense of unity. As Daniel Webster wrote in 1820, “Two thousand miles westward from the rock where their fathers landed, may now be found the sons of the Pilgrims ... [cherishing the blessings] of wise institutions, of liberty, and religion.”

And what of the Puritans? Ken Curtis writes, “The Puritans who settled in New England laid a foundation for a nation unique in world history… Their values and principles, though sometimes secularized and removed from their religious foundations, continued to mold American thought and practices in the next centuries.”

Perhaps every American has a little Puritan and a little Pilgrim: a national personality with a closed, judgmental heart yet an open, accepting spirit of community.

“Pure religion and undefiled before God and the Father is this, To visit the fatherless and widows in their affliction, and to keep himself unspotted from the world” (James 1:27).

Further Reading:

John Winthrop: American Nehemiah

Who Are the Most Important Puritans?

Puritan John Owen Focused on Christ

Why Did the Puritans Settle in America?

Cotton Matter: Witch Trial Advisor and Puritan Pastor

Photo Credit: Getty Images/TonyBaggett