John Wesley spent just two years in the American colonies, and he had a pretty dismal time of it. Yet that trip led to major changes in Wesley's life, and his work in turn did much to shape the religious climate in America.

When he boarded an ocean-going ship in 1735, bound for Georgia, John Wesley was already a very religious man. Son of an Anglican minister, he had studied at Oxford, where he co-founded The Holy Club, a group of students who aimed to be methodical about their personal holiness. Within this group were Charles Wesley (John's hymn-writing brother) and a young preacher named George Whitefield. Their methodical approach is what caused them to be called "Methodists."

Despite his striving for righteousness, John Wesley was missing something. Before his American voyage, he wrote: "My chief motive is the hope of saving my own soul. I hope to learn the true sense of the Gospel of Christ by preaching it to the heathen."

The colony of Georgia was quite new. James Oglethorpe led a group of settlers there in 1733, intending to establish it as a non-slavery colony. John Wesley was asked to serve there as a minister to the English settlers and a missionary to the friendly native tribes in the area.

Serenity in the Storm

He set out in October, 1735, on a ship carrying 80 English colonists and 26 Moravians. John got to know these Moravian Christians, appreciating their radiant joy and deep devotion. This was especially apparent one night just as the Moravians had begun their evening psalm-singing. The wind-swept sea lashed at the ship, ripping the mainsail and pouring through the decks. The English passengers were screaming, but the Moravians kept singing.

"Weren't you afraid?" he asked one of the Moravians after the storm was over. "Weren't your women and children afraid?"

The Moravian gently responded, "No. Our women and children are not afraid to die."

After the ship landed, Wesley continued similar conversations with a Moravian pastor named Spangenberg, who launched some challenging questions of his own. "Have you the witness within yourself?" the pastor asked John. "Does the Spirit of God witness with your spirit that you are a child of God?" Wesley didn't know what to say. "Do you know Jesus Christ?" the pastor pressed. "I know he is the Savior of the world."

"True," the Moravian responded, "but do you know he has saved you?"

John Wesley was clearly a very religious man. He had not only trained for the ministry, but he formed a club devoted to finding new levels of righteousness. He was not only an Anglican minister, but a missionary, traveling across an ocean to spread the Christian faith. But what was this Christian faith he was spreading? Was it merely a matter of seeking righteousness? Or was there more? What was it that gave those Moravians such confidence in the face of death? How could they sing joyfully when others were shrinking with fear? Whatever they had, John Wesley feared he didn't have it.

Yet he powerfully preached a message of spiritual discipline, railing against vanity and fancy clothes. Initially, many colonists responded out of curiosity more than anything else. Someone said to Wesley, "The people say they are Protestants, but as for you, they cannot tell what religion you are of. They never heard of such a religion before, and they do not know what to make of it." John began holding a sort of Bible study group on Sunday afternoons, a feature he would later use in England with great effect, but in general Wesley's Georgia ministry was difficult. He fell in love with Sophia Hopkey, the niece of the chief magistrate, and courted her for some months. Perhaps fearing that this relationship would inhibit his ministry, he decided not to marry her, and she soon wed someone else. This caused Wesley great pain, and he took it out on her, publicly rebuking her for various sins and refusing to offer her communion. Her new husband took Wesley to court for this, and soon others were filing complaints as well. In December, 1737, he left for England.

Enter George Whitefield

But fortunately, Wesley's impact on America was just beginning. Wesley's return voyage crossed paths with George Whitefield's first trip to the colonies. A long-time friend of the Wesleys, Whitefield was coming to Georgia to oversee an orphanage in John's parish. But over the next decade, Whitefield would ride on horseback throughout America, preaching in any church that would have him—and often in open fields. Whitefield was a major player in what became known as the Great Awakening.

In many ways, Whitefield picked up where Wesley had left off. He was just as interested in a thoroughgoing righteousness, but he offered an added ingredient—spiritual rebirth. Wesley's message was heavy on law, Whitefield's on grace. "Ye must be born again," was Whitefield's key verse, and people gladly grasped the spiritual regeneration that would help them meet Wesley's challenges. Later, Whitefield declared, "The good Mr. John Wesley has done in America is inexpressible. His name is very precious among the people; and he has laid a foundation that I hope neither men nor devils will ever be able to shake." Perhaps Whitefield was being kind to his friend, but Wesley might have been the schoolmaster that led people to Whitefield, and, of course, ultimately to Jesus.

Wesley saw his American adventure as an utter failure. "I went to America to convert the Indians," he wrote later, "but, O! who shall convert me?"

John kept in touch with some of the Moravians he had met on his trip to America. At their invitation, on May 24, 1738, he attended a religious meeting on Aldersgate Street in London and heard someone read from Martin Luther's Commentary on the Book of Romans. He felt his heart "strangely warmed." Suddenly he knew that Jesus had saved him from the law of sin and death. "It pleased God," he wrote later, "to kindle a fire which I trust shall never be extinguished."

Ablaze in England and America

The fire blazed quickly in England over the next few years. Whitefield came back from Georgia for a time and preached powerfully. Many church leaders were upset with his emphasis on rebirth—wasn't church membership good enough?—and so they closed their doors to Whitefield. No matter, the preacher drew larger audiences in the open air. And these services drew a different kind of hearer, the kind that had long felt uncomfortable in the established church. Commoners, poor folks, questioners, all flocked to hear this new message of salvation by faith in Jesus, and many committed themselves to Christ. A revival broke out in Bristol under Whitefield's preaching. When time came for him to return to Georgia, he invited John Wesley to take over the preaching in Bristol.

Whitefield's 1739-40 trip turned out to be America's wake up call. Landing in Delaware, he traveled north to Massachusetts and even Maine, and back south to Georgia, getting enormous response wherever he preached. Ben Franklin quipped, "From being thoughtless or indifferent about religion, it seem'd as if all the world were growing religious, so that one could not walk thro' the town in an evening without hearing psalms sung in different families of every street."

It would be hard to overstate the importance of the Great Awakening on American history. It certainly created a spiritual undercurrent for the political developments of the 1700s. Did it help knit together the religiously diverse colonies? Did it provide the spark needed to break out of old constraints (religious and political) and move in some new directions? Certainly the Great Awakening was not just a Methodist event, but the seeds were planted back in those Holy Club meetings at Oxford, as Whitefield chatted with the Wesleys and other college pals.

Meanwhile, the evangelical awakening continued in England, under John Wesley's leadership. Response to the preaching in Bristol and elsewhere created a challenge for Wesley and the other Methodists. What do you do with all the newly converted? You start fellowship groups, accountability groups, Bible study groups, and you train the new converts in the ways of righteousness. With his great gift for organization, John Wesley soon set up Methodist societies throughout Great Britain, which included "classes" like his old Sunday afternoon Bible group. For decades the Wesleyan movement grew within the Church of England.

But the Anglican church already had been slow to send new ministers to the colonies, and the growing tensions with America made things worse. Yet the Great Awakening had created a huge need for leadership, which Wesley was determined to meet. In 1784, a year after the United States won its independence, Wesley began to ordain "elders" to lead the American Methodists.

The Methodist church then exploded across the American continent in much the same way that it had swept through England and Scotland. The traditions of open-air services and circuit-riding preachers fit perfectly with the American frontier. The Methodists weren't chained to church buildings or old forms. It was a new faith for a new nation. And it didn't hurt that Francis Asbury, the first Methodist bishop ordained in America, had been an outspoken supporter of the American Revolution. In Kentucky and pushing westward, "camp meetings" became all the rage. Settlers would gather from miles around to sing and pray and hear some circuit-rider (usually a Methodist) preach the Word—thus developed a uniquely American form of worship. By 1830, Methodists formed the largest denomination in the U.S.

John Wesley died in 1791, possibly the most important Englishman of the eighteenth century. Through the extended influence of people like Whitefield and Asbury, he was exceptionally important to America as well.

(First published April 28, 2010)

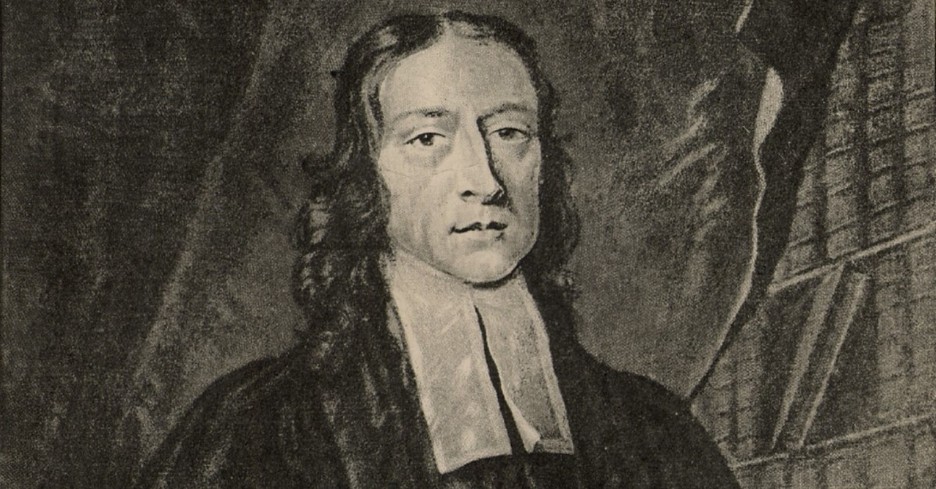

Photo Credit: © Getty Images/Photos.com