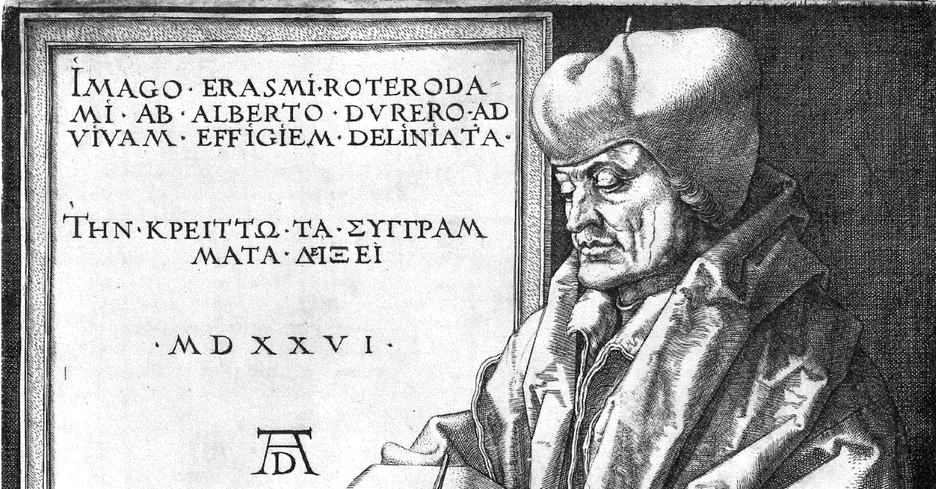

Erasmus never joined the Protestant movement, but many scholars would argue he set the stage for the Reformers.

Here's what you need to know about his influence and legacy:

Table of Contents

Erasmus Loaded the Reformation Cannon

Erasmus loaded the cannon that Luther fired. The greatest scholar of his day, Erasmus rammed two shots into the barrel of the Reformation.

The first shot was a satire titled, The Praise of Folly, which poked fun at the errors of Christian Europe. For example, Erasmus reminded his readers that Peter said to the Lord, "We have left everything for you." But Folly boasts that, thanks to her influence, "there is scarcely any kind of people who live more at their ease" than the successors of the apostles.

The second shot was a Greek New Testament. For centuries, Jerome's Latin translation, the Vulgate, was the Bible of the Church. However, Jerome's translation had deficiencies. Erasmus reconstructed the original New Testament as best he could from Greek texts and printed it. In a parallel column he provided a new Latin translation. What is more--and this could have cost him his life--he added over a thousand notes that pointed out common errors in interpreting the Bible. He attacked Rome's refusal to let priests marry although some lived openly with mistresses; and he denied that the popes have all the rights that they claim. The scholar also challenged practices not taught in scripture: prayers to the saints, indulgences, and relic-worship.

After years of work, Erasmus was ready to release his book. He wondered how he could avoid trouble. One way was to link the New Testament with some great man's name. And so, on this day, February 1, 1516, Erasmus dedicated his New Testament to Pope Leo X. He had gotten the Pope's permission the year before. In a soothing letter written to Leo a few months later, he assured him that he meant no harm. "We do not intend to tear up the old and commonly accepted edition [the Vulgate], but amend it where it is corrupt, and make it clear where it is obscure."

Just in case the authorities should be angry, Erasmus pointed out that the ideas were not new with him. He quoted the greatest church fathers in support of his corrections. It would be a lot harder for intolerant factions to argue with dead heroes than with him!

Like Jerome's translation, Erasmus' New Testament was not completely accurate either. He did not have access to the best manuscripts. Nonetheless, it was enough of an improvement over the old that Martin Luther, William Tyndale, and other translators based their vernacular versions on it. Furthermore, they picked up Erasmus's calls for reform.

The result was that the Reformers broke away from the Roman Catholic church. For a time Erasmus and Luther remained friends. But Luther's words were so violent that Erasmus could not accept them. When Erasmus did not agree with Luther, the Reformer called him all sorts of names, such as "secret atheist."

Erasmus, who thought that the Christian life meant living in the peace of Christ, was hurt. He was in grave danger from both camps. Protestants said he held onto too much that was Catholic; the Catholics threatened him because they claimed he was wrecking the church. Erasmus had to flee from Catholic Louvain to escape being burned to death at the stake.

Erasmus had such a reputation for wit that people were willing to wait quietly for him to answer a question. Frederick the Wise once asked the scholar his opinion of Luther. Erasmus thought while the king waited silently. Finally he answered, "Two 'crimes' Luther has committed: he has attacked the tiara of the pope and the bellies of the monks." Frederick laughed.

We do not often hear of Erasmus. Yet Anabaptists, Zwinglians, and Lutherans claimed to be his true children. His Bible and his wit helped bring about the Reformation.

Bibliography:

1. Allen, John. One Hundred Great Lives. New York: Journal of Living, 1944.

2. Bainton, Roland. Erasmus of Christendom. New York: Scribner, 1969.

3. Bainton, Roland. Here I Stand. New York : New American Library, c1950.

4. "Erasmus." Encyclopedia Americana. Chicago: Encyclopedia Americana corp., 1956.

5. Faulkner, John Alfred. Erasmus the Scholar. Cincinnati: Jennings and Graham, 1907.

6. Runes, Dagobert D. A Treasury of Philosophy. New York: Philosophical Library, 1945; p.381.

7. Russell, Bertrand. Wisdom of the West. New York: Fawcett, 1964; pp. 230 - 231.

8. Zweig, Stephan. Erasmus. New York, The Viking Press, 1934.

Last updated May, 2007.

("Erasmus Loaded the Reformation Cannon" by Dan Graves first published on May 3, 2010)

Glarean Blessed Erasmus

One of the greatest teachers and scholars at the time of the Swiss Reformation was Heinrich Loreti. Known by the name Glarean, because he was born near Glarus, Switzerland, he came to Basel in 1514 as a private scholar and a proctor (supervisor) of younger men. At that time, the university required its students to live with such proctors. Fifteen or more men would room with one of these graduate students, who added his own instruction to their education.

Glarean perfected his students' knowledge of Latin and Greek, mathematics, geography, and classical literature. He could have helped them with music, too, for he made an original mark in that field. So gifted was Glarean that one of his enthusiastic pupils wrote, "I doubt whether there are ten like him in all Switzerland."

Erasmus, the humanist and scholar who did more than anyone to set the Reformation going, made a deep impression on Glarean. On this day, September 5, 1516 (a year before Martin Luther posted his 95 theses) Glarean wrote a letter to Erasmus, revealing how the older man had inspired him. In it he said, "You taught me to know Christ and not only to know him but to imitate him, to honor him and to love him."

Glarean attempted to impart the new humanism to his students. Praising him in a 1517 letter to a Bishop in Paris, Erasmus noted that he had rejected fruitless theology and was studying Christ from the sources. "He has great knowledge of history, and is remarkably able in music, cosmography, and mathematics, deserving to be called master in these fields. In respect to morals, he has a good and clean character, and is devoted to piety."

One of the greatest teachers and scholars at the time of the Swiss Reformation was Heinrich Loreti. Known by the name Glarean, because he was born near Glarus, Switzerland, he came to Basel in 1514 as a private scholar and a proctor (supervisor) of younger men. At that time, the university required its students to live with such proctors. Fifteen or more men would room with one of these graduate students, who added his own instruction to their education.

Glarean perfected his students' knowledge of Latin and Greek, mathematics, geography, and classical literature. He could have helped them with music, too, for he made an original mark in that field. So gifted was Glarean that one of his enthusiastic pupils wrote, "I doubt whether there are ten like him in all Switzerland."

Erasmus, the humanist and scholar who did more than anyone to set the Reformation going, made a deep impression on Glarean. On this day, September 5, 1516 (a year before Martin Luther posted his 95 theses) Glarean wrote a letter to Erasmus, revealing how the older man had inspired him. In it he said, "You taught me to know Christ and not only to know him but to imitate him, to honor him and to love him."

Glarean attempted to impart the new humanism to his students. Praising him in a 1517 letter to a Bishop in Paris, Erasmus noted that he had rejected fruitless theology and was studying Christ from the sources. "He has great knowledge of history, and is remarkably able in music, cosmography, and mathematics, deserving to be called master in these fields. In respect to morals, he has a good and clean character, and is devoted to piety."

Among the pupils Glarean supervised was Conrad Grebel, who became a significant leader of the Swiss Brethren. Another, at the opposite pole, was Aegidius Tschudi who became a famous historian and defender of Catholicism in Switzerland. But many others passed under Glarean's care.

However, when Glarean is remembered today, it is usually because of his study of musical modes. (In a mode, the eight tones in a octave are arranged according to a fixed scheme.) Two of his modes are similar to our major and minor scales. He claimed that there are twelve modes, or a Dodecachordon. The system is not used and is too technical to explain here, but Glarean's point was that many of these modes were in use by contemporary musicians who did not even realize it. Glarean gave his modes Greek names: the Dorian, the Phrygian, and so forth.

Glarean was friends with several of the Reformers, men such as Ulrich Zwingli and Oecolompadius. At first he was happy with Luther's ideas, but as time passed he grew disenchanted with the violent course the Reformation took and in the end, he remained a Catholic.

Bibliography:

1. Bender, Harold S. Conrad Grebel c. 1498-1526; the founder of the Swiss Brethren sometimes called Anabaptists. (Scottsdale, Pennsylvania: Herald Press, 1950.

2. Hartig, Otto. "Henry Glarean." The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton, 1909.

3. Mortensen, Kurt. "Glarean's Dodecachordon." http://www.kurtmortensen.org/pn-dodecachordon.html

4. Various internet articles.

Last updated July, 2007

("Glarean Blessed Erasmus" by Dan Graves, MSL, first published on May 3, 2010)

Further Reading:

What Was the Protestant Reformation?

From the Death of the Elector of Saxony, to the Conclusion of Luther's Controversy with Erasmus

The Five Solas - Points from the Past that Should Matter to You

Photo Credit: © Getty Images/burdem