Who were the Anabaptists?

The Anabaptists ( or "re-baptizers") were one of several smaller groups in church history that endured unspeakable suffering to establish and maintain their witness.

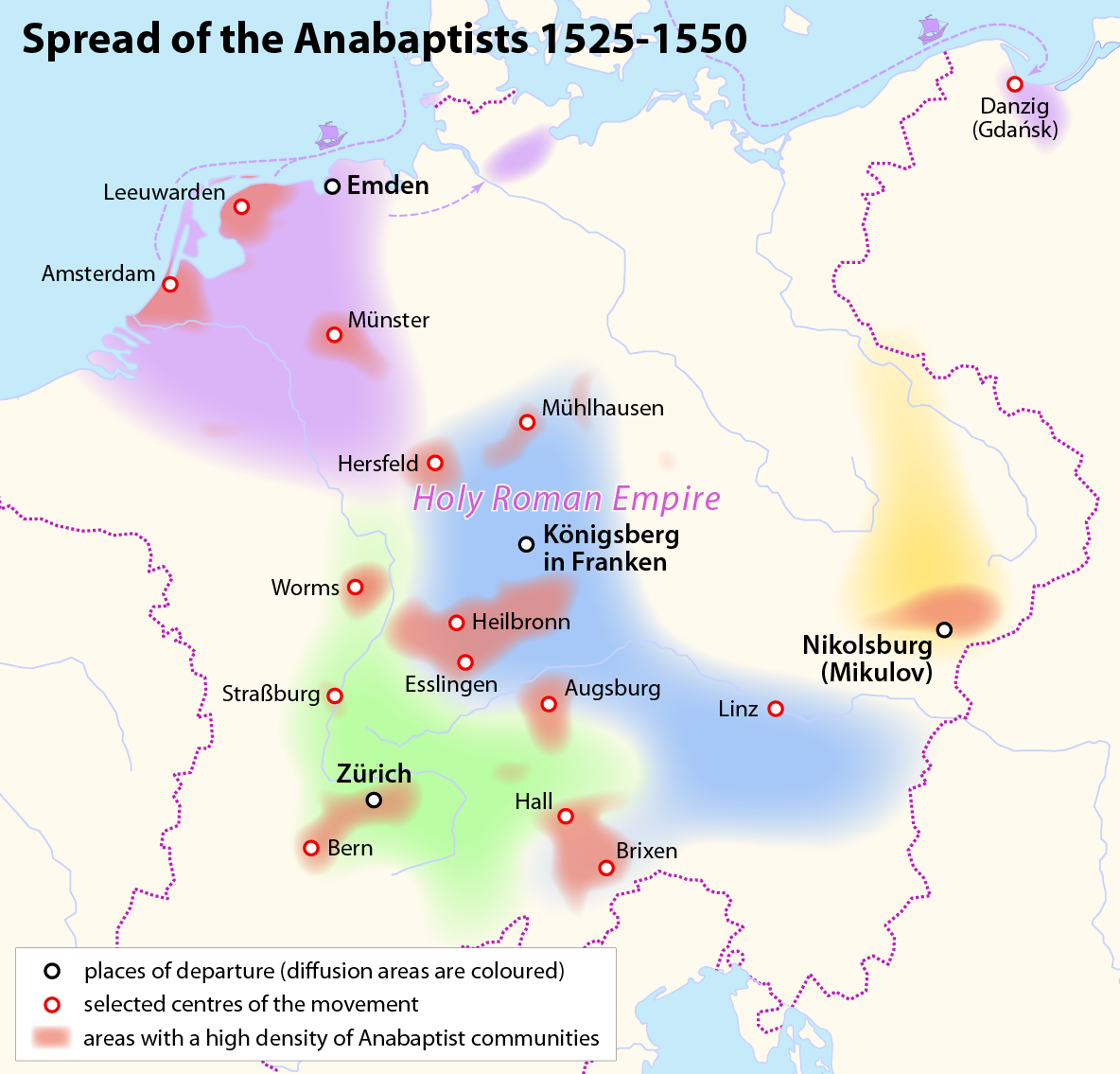

They began in the midst of the reform at Zurich under Zwingli in the mid-1520s. Some felt that Zwingli and the reform there were not going far enough or fast enough. More was needed, they felt than to reform a corrupt, unfaithful church. They wanted to return to a New Testament church.

Pictured Below: The Spread of Anabaptists in the 16th Century

Separate Church and State and Don't Baptize Babies

Two issues are important to mention. First, they thought that reformers like Luther and Zwingli were still captive to a political marriage of church and state. The Anabaptists insisted that the church be separate, govern itself, and have no official ties to the state. This sounds rather sane and acceptable to us today, but then, it set off a frightening explosion. Throughout history until that time, religion and government had always been linked together.

Second, these believers could find nothing about infant baptism in the Bible, so they concluded it was an invention of a corrupt church and, therefore, illegitimate. They would get baptized all over again as believers and form a believer's church that was composed only of the converted.

Zwingli gave them room at first, and a public debate on baptism was held at Zurich in 1525. The conclusion by the council: infant baptism was to be maintained. The dissidents did not accept the council's judgment and continued to press their points and stir unrest. When they would not accept "correction," some were jailed and drowned.

Pictured Below: A Statue of Zwingli in Zurich.

Sattler in the saddle

One of the early Anabaptist leaders was Michael Sattler. Born around 1490 in southwestern Germany, Sattler became a monk at the monastery of St. Peter's of the Black Forest and there rose to the position of Prior, next in authority under the Abbot. Disillusioned by the corruption he saw in church life, perplexed by his study of the Bible, and moved by the horrible conditions of peasant life, Sattler left the monastery. He was a man in painful search for truth. He lived for a while with Anabaptists north of Zurich and became familiar with their convictions, meanwhile learning the weaver's trade to support himself. Pictured Below: A Painting of Sattler from 1828

His association with Anabaptists led to his arrest in 1525 at Zurich, but he was released when he agreed to renounce Anabaptism and permanently leave the Zurich area.

In 1526, he married Margaretha who had recently left a Catholic religious community of women. She would prove a courageous companion for the brief marriage they shared.

Sattler's convictions strengthened, and he came back to the Anabaptists, or Swiss Brethren, as they were called. The movement was spreading but severely opposed, almost everywhere. It attracted its fair share of colorful opinionated dissidents. It had no structure. Pressure from without, combined with confusion and discord from within, threatened the very survival of the infant Brethren cause.

Secret council, Sublime confidence

A secret meeting of their key leaders was convened in the Swiss town of Schleitheim on February 24, 1527. A confession was drawn up to try to bring some order within their ranks. Scholars are convinced that it was the former monk, Michael Sattler, drawing upon his experience of the discipline and structure of the monastery who wrote the "Schleitheim Confession." It was the necessary catalyst to give the Brethren a needed sense of identity and direction.

Sattler moved on to take up pastoral duties at Horb, an area under the Austrian control of Ferdinand, an aggressive Catholic persecutor of alleged heretics. Michael, his wife, and others were arrested and kept in jail for nearly twelve weeks. He was brought to trial and his calm, reasoned, and brilliant defense of his now fervently held Anabaptist convictions failed to move his accusers. Awaiting death, he wrote to his flock: " In such dangers, I have surrendered myself entirely to the will of the Lord and am, with all my brothers, my wife, and some other sisters, prepared for witness to him even unto death." On May 20, 1527, his tongue was cut out, he was tortured and then burned alive. As the flames consumed him, he held up his forefingers as a prearranged sign to his fellow believers, verifying that God would give the strength to endure faithfully to the end. A few days later, after refusing a final opportunity to recant, Margaretha followed her husband into martyrdom and was drowned.

The Settlers were only two of scores of Anabaptists who remained faithful unto death. Their stories would undergird the Anabaptists for generations as they were scorned, exiled, ridiculed, and persecuted by governments, Catholics, and Protestants alike. Anabaptist descendants today can be found in the Mennonites, Amish, Hutterites, Brethren in Christ, and other groups.

|

The Schleitheim ConfessionOriginally called The Brotherly Union of Some Children of God, "The Schleitheim Confession" was a kind of an Anabaptist Manifesto bringing the fledgling movement together. The Anabaptists affirmed the central historic doctrines of the faith. But in this confession they were dealing with problem areas - what to them were the hot issues on which they had to clarify their positions. They covered seven points.

|