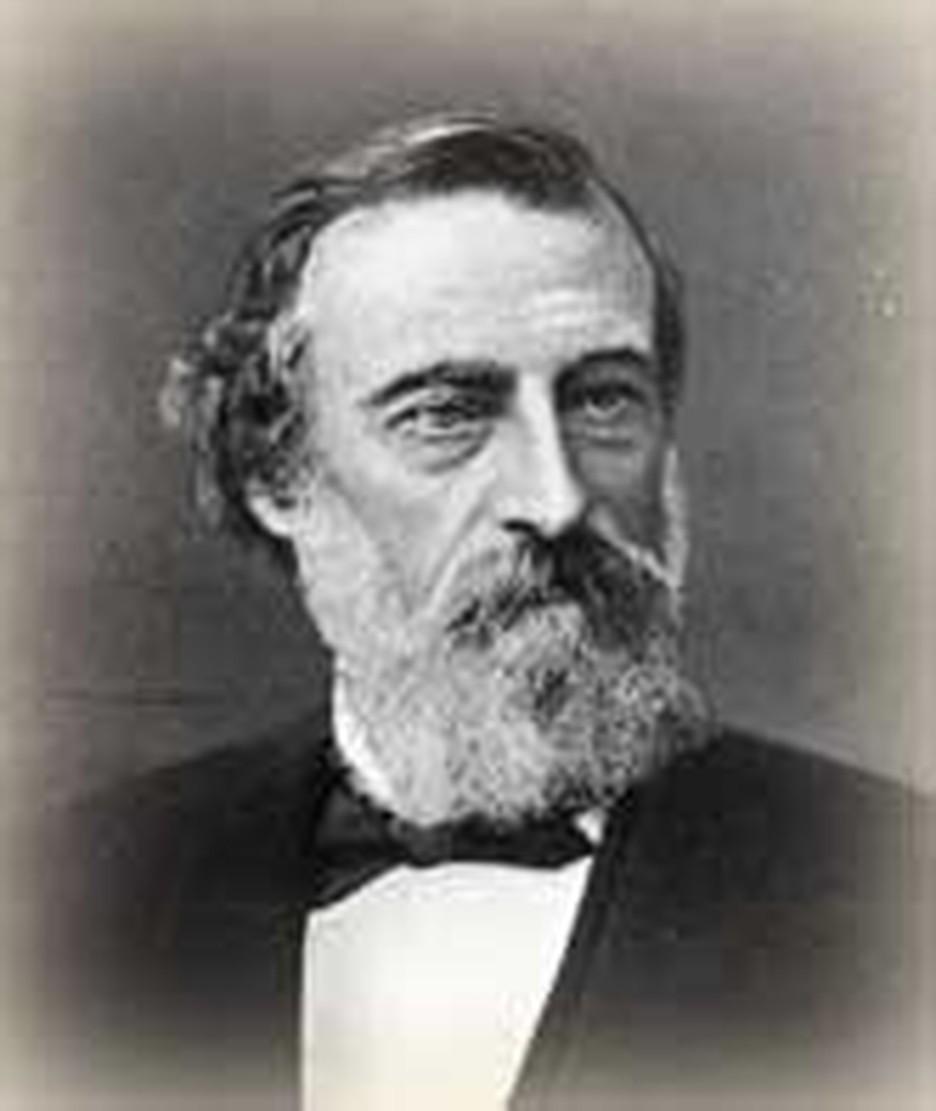

Like his youthful hero David Livingstone, James Stewart hailed from Scotland. Born in Edinburgh in 1831, he vowed at 15 to become a missionary. He had a plow in his hands at the time. His faith was already active in deeds; a strong boy, he regularly carried a lame lad a mile to Sunday School. This faith had not formed in a vacuum, for his father belonged to the Free Church of Scotland and threw open his barn to services when needed.

During Stewart's student days, he took every scientific course he could and tutored young men while himself still in training. It is some indication of his breadth of interest and power of mind that he published two textbooks on botany while yet a theological student. He acquired medical training, too. Livingstone's books kept his interest fixed on missions while he studied. His years of education paid great dividends in Africa.

On this day, August 13, 1861 he landed at Cape Town in the company of Livingstone's wife, Mary, who was on her way back to Africa to join her husband. Stewart and Livingstone were beside Mary's bed when she died in 1862. Stewart then teamed up with Livingstone, intending to prospect for the best place to open an industrial mission. His hero worship soon lost its luster. Disillusioned with Livingstone, he flung his copy of Livingstone's inaccurate Missionary Travels and Researches into the Zambesi.

Stewart would settle into a work less glamorous but more enduring than exploration. Interested in African education, in 1867 he became the principal of Lovedale, a pioneer educational establishment in South Africa. He held this post almost forty years and made the school the premiere educational establishment for blacks in South Africa. In addition to a general education, Lovedale offered practical arts such as blacksmithing, carpentry, masonry, and wagon-making.

The impact of this work was tremendous. From the start, Lovedale students filled responsible positions throughout Africa. They preached, clerked, taught, and ran businesses.

Stewart held that every person puts more value on that which he or she has to pay for than on things given free. And so he insisted the South Africans pay for their education. When the Fingoes (Mfungi) asked for a school of their own along the lines of Lovedale, he urged that they raise the money themselves. Their efforts gathered over £4,000 and the Blythswood Institution in Transkei was created. Stewart founded two other mission stations in the later part of his life and left a blueprint for a college which was built after his death. In addition to all his other work, he founded a hospital.

He wrote Lovedale Past and Present, urging African education and Dawn in the Dark Continent, long the standard work on African missionary technique.

Bibliography:

- Neill, Stephen. Concise Dictionary of the Christian World Mission. Edited by Stephen Neill, Gerald H. Anderson [and] John Goodwin. Nashville, Abingdon Press, 1971.

- Davies, Horton. Great South African Christians. Cape Town, New York: Oxford University Press, 1951.

- Moorhouse, Geoffrey. The Missionaries. Philadelphia, Lippincot, 1973.

- Robinson, Charles Henry. History of Missions.

- Stewart, James. Dawn in the Dark Continent; or Africa and its missions. Edinburgh: Oliphant Anderson & Ferrier, 1903.

- -------------------. Lovedale, South Africa. Edinburgh, Andrew Elliot; Glasgow, David Bryce and son 1894.

- Wells, James. Stewart of Lovedale; The Life of James Stewart. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1909.

.jpg)